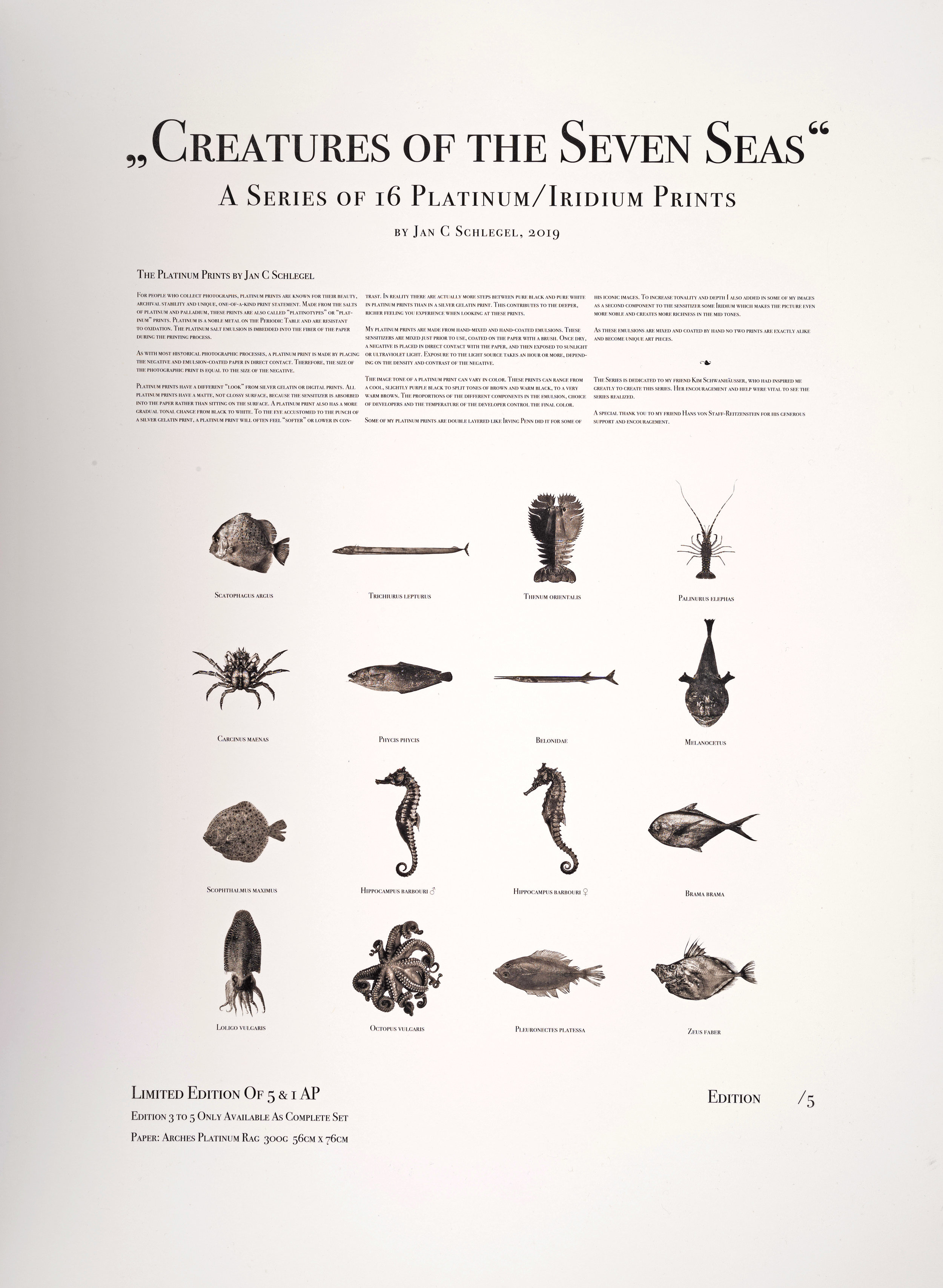

A Personal Discovery of the Very Basis of Our Life on Earth

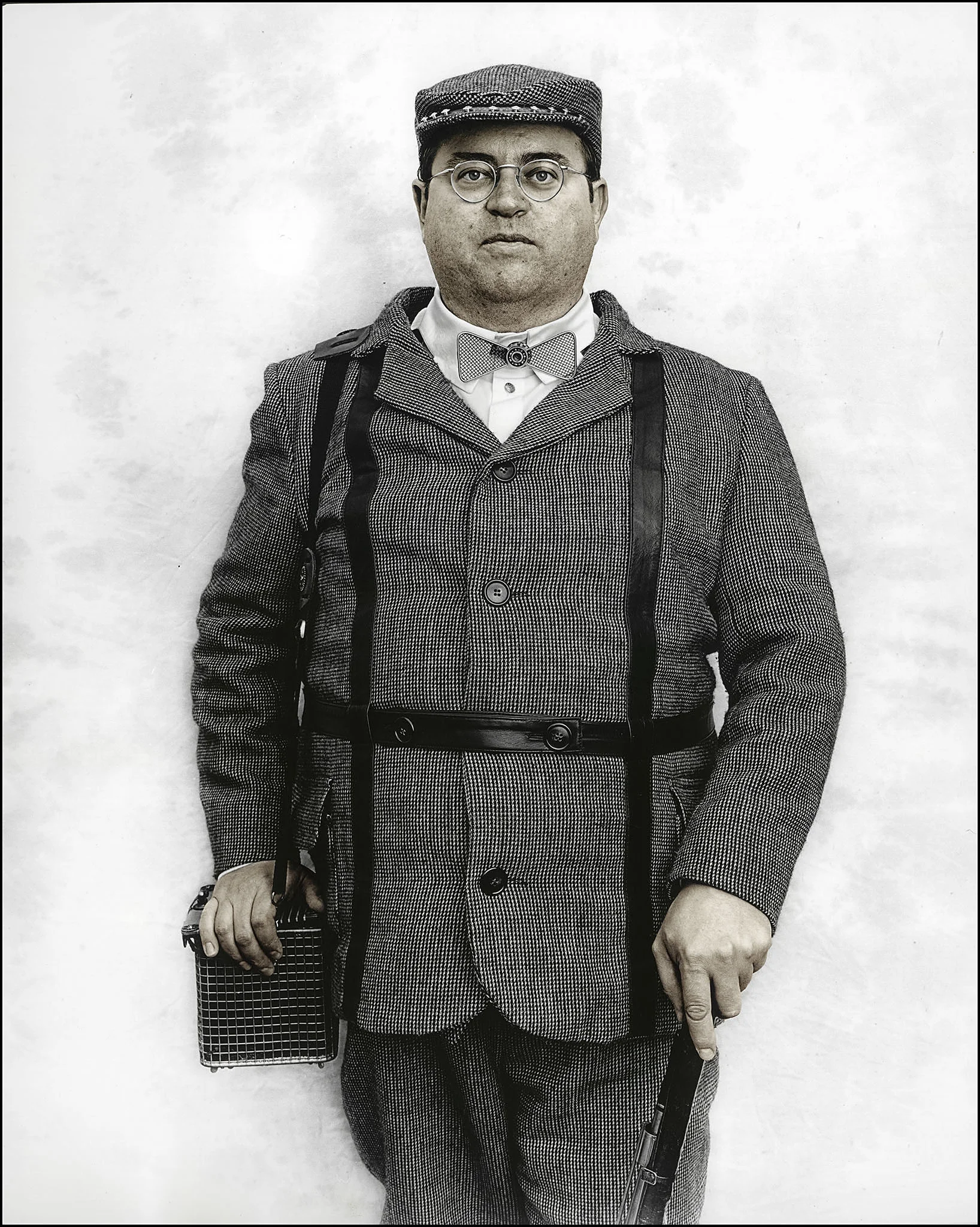

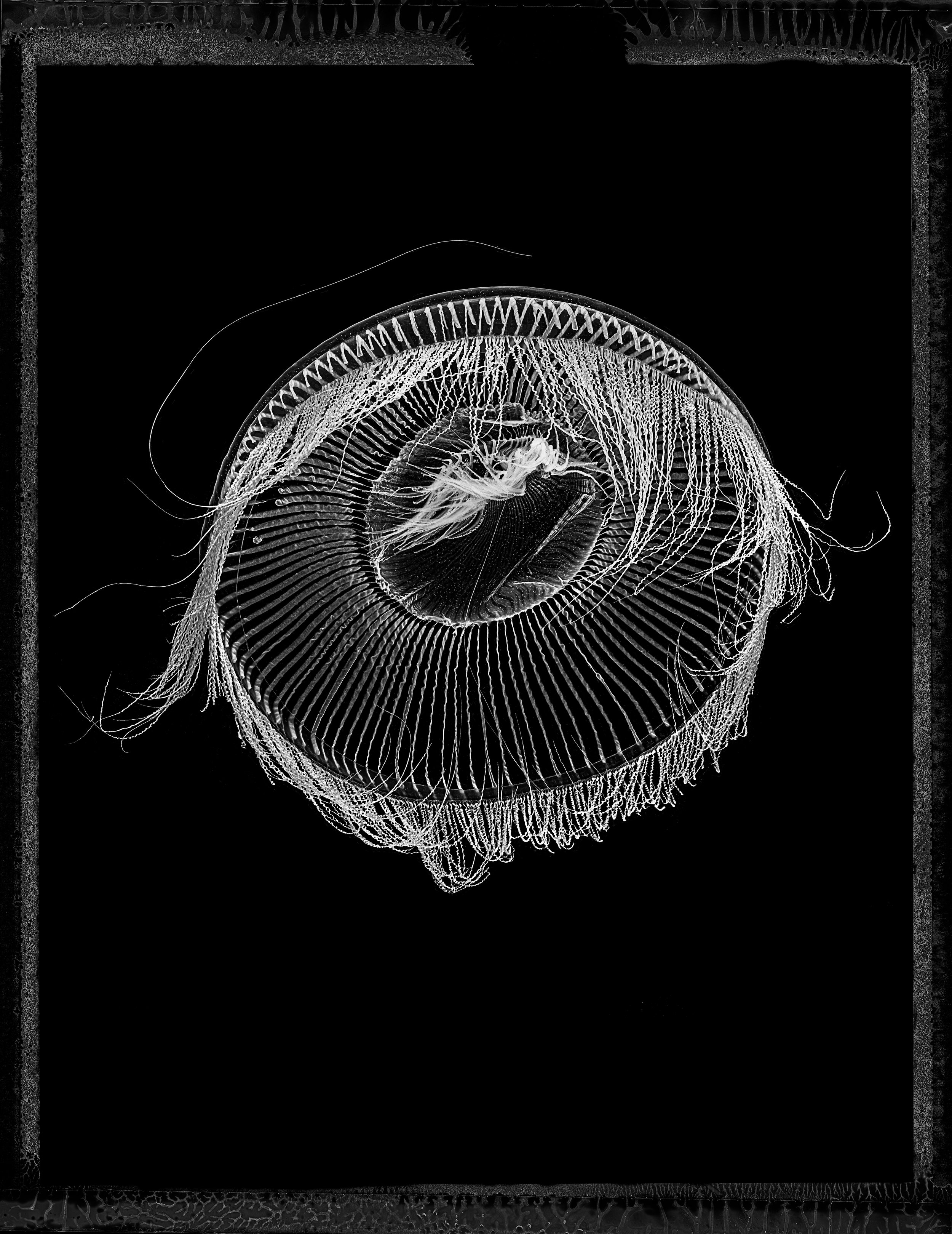

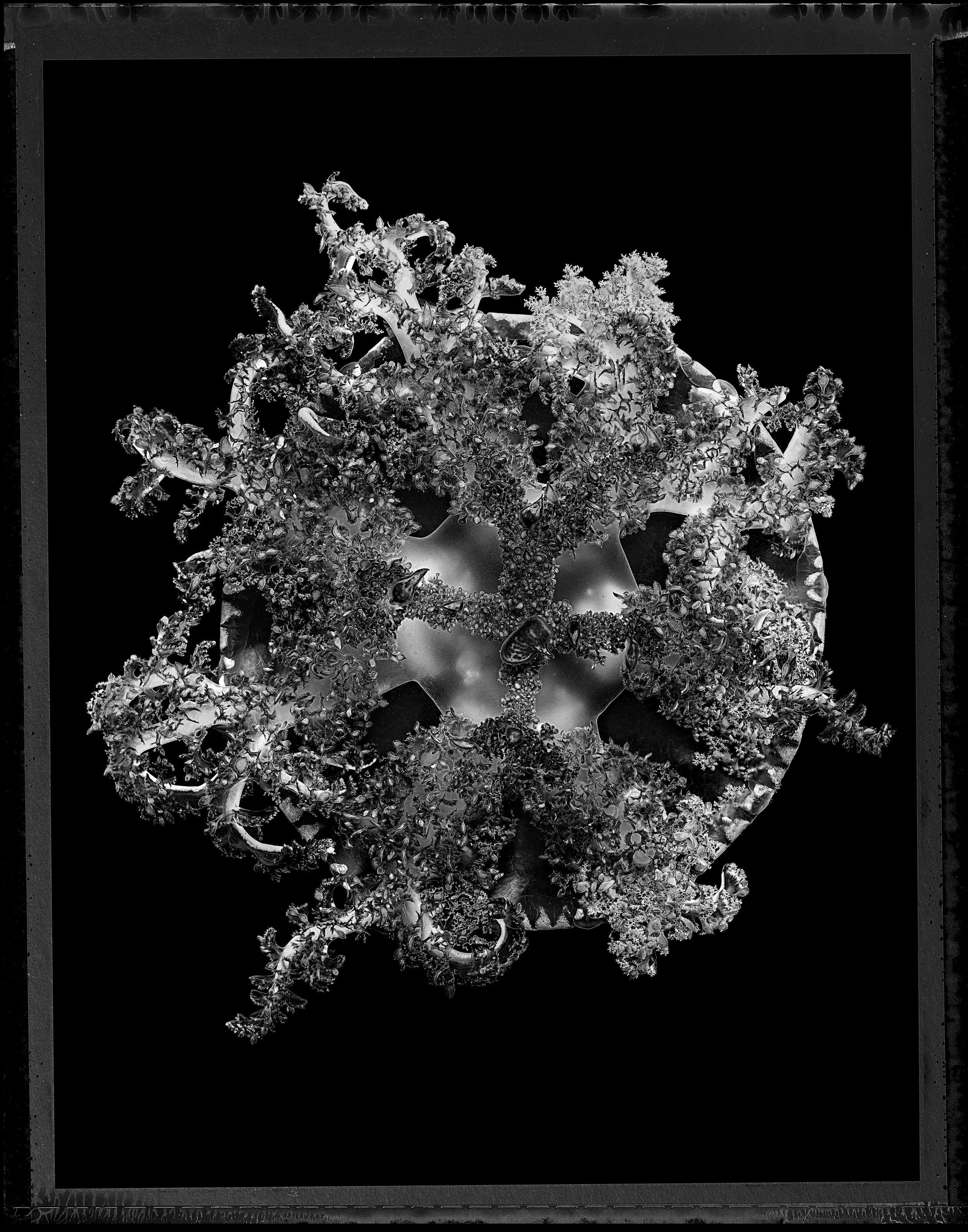

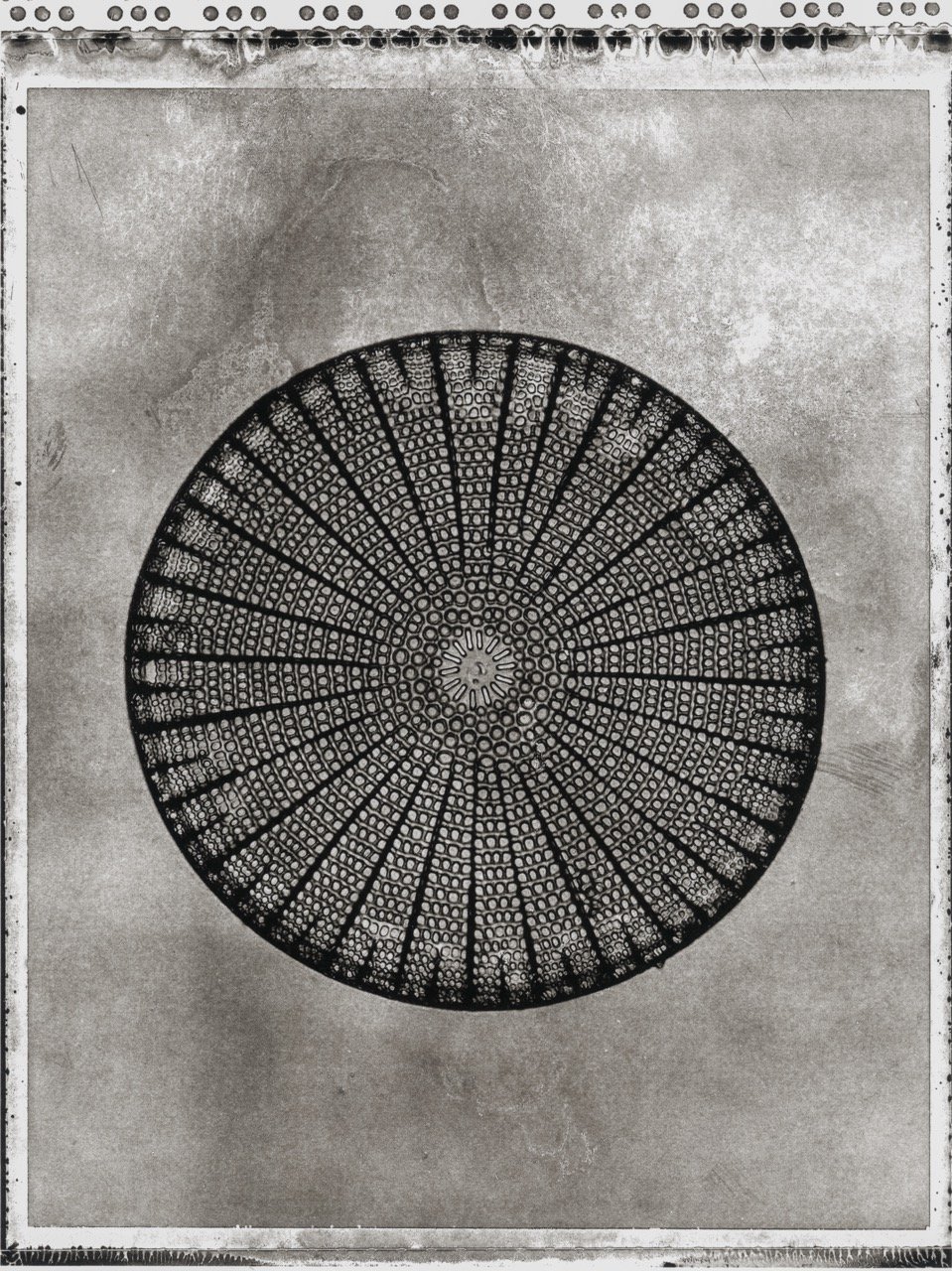

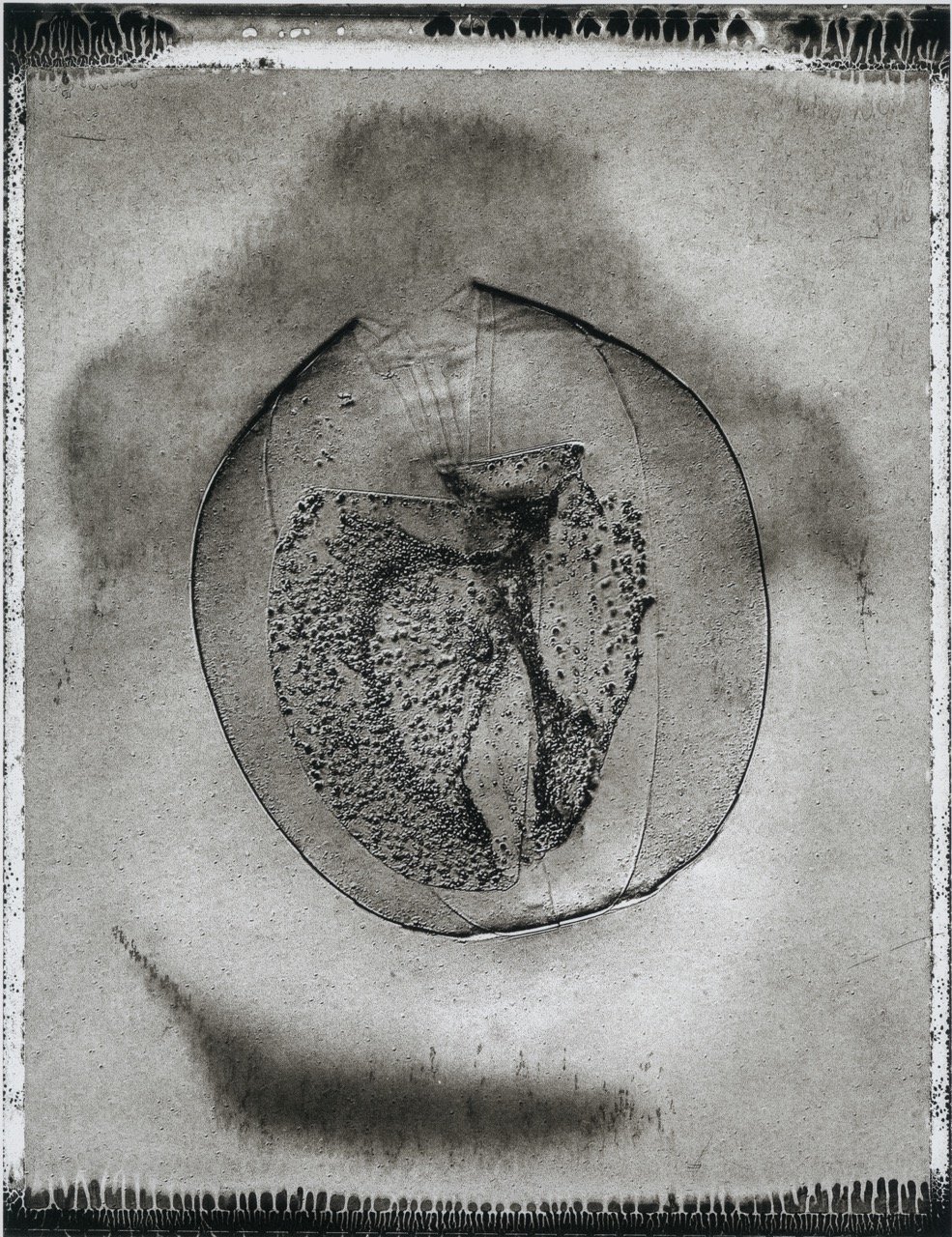

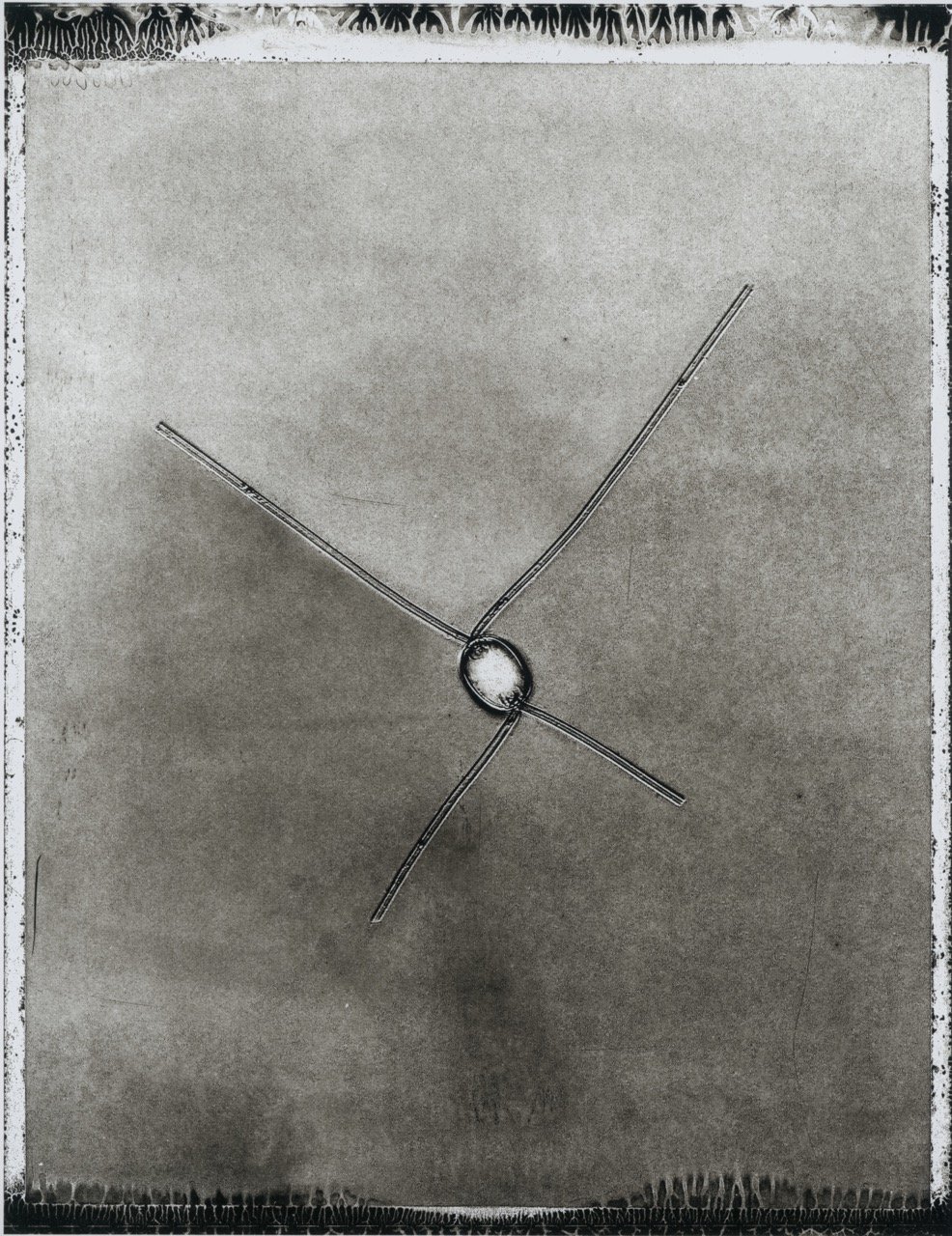

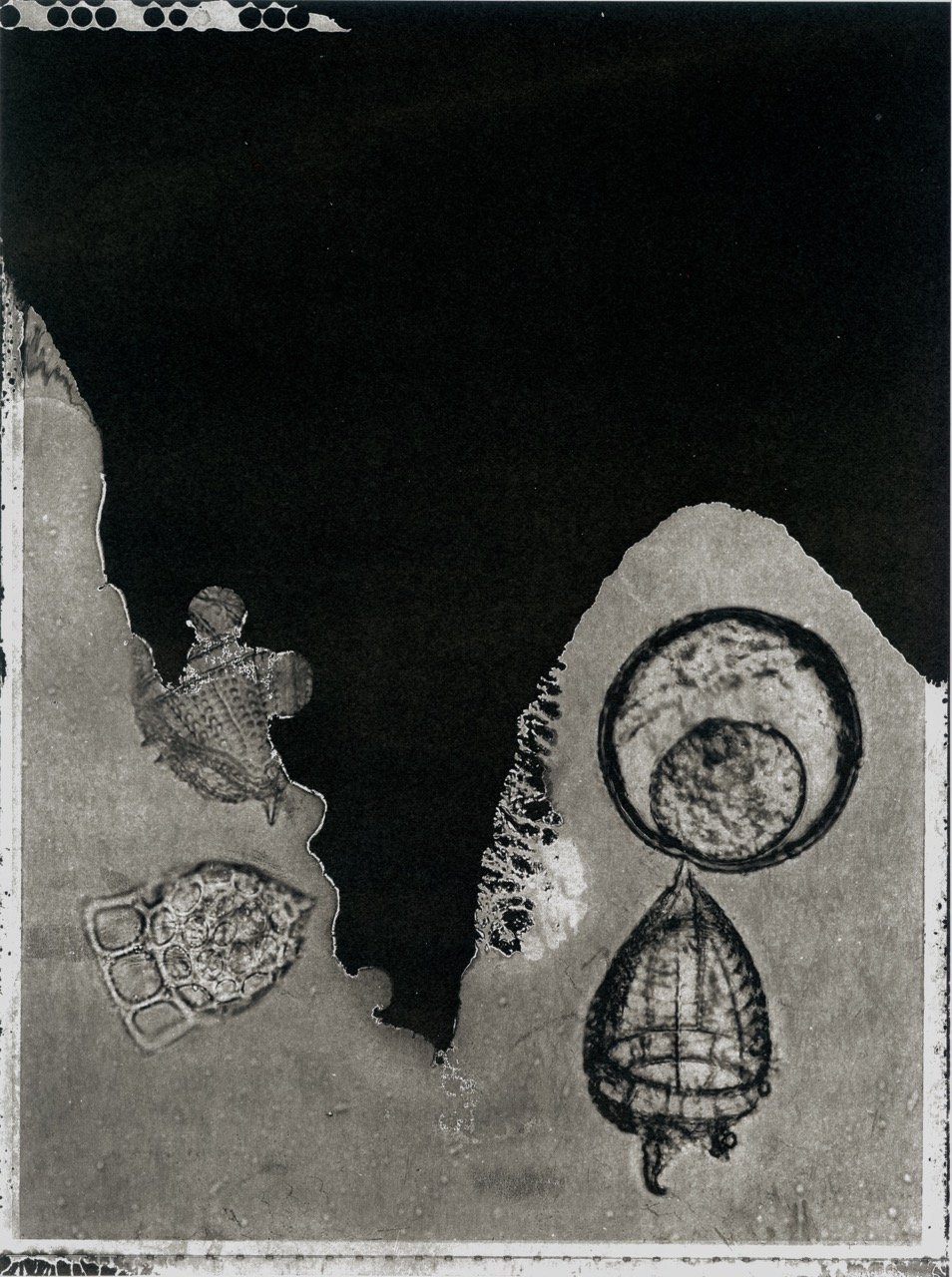

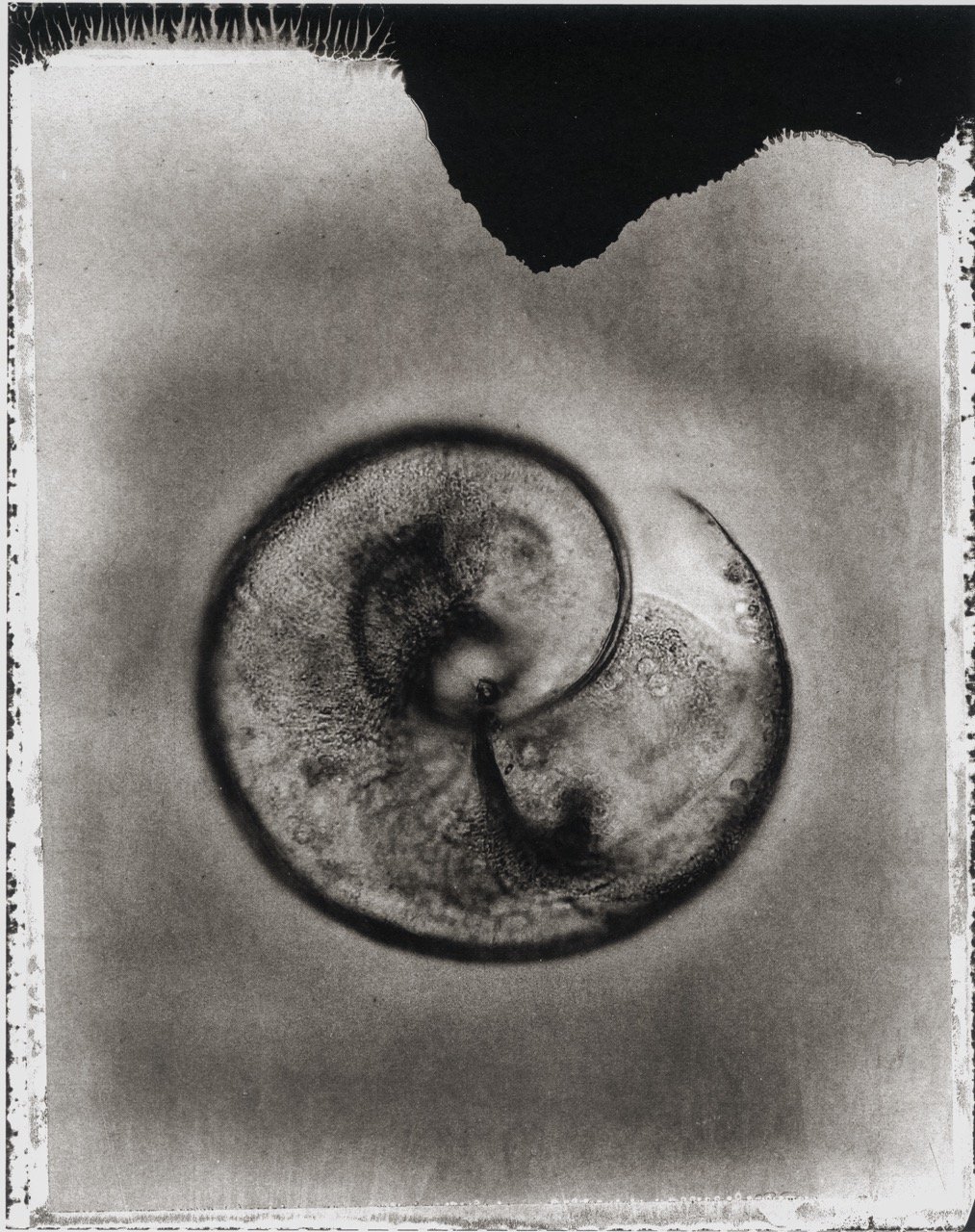

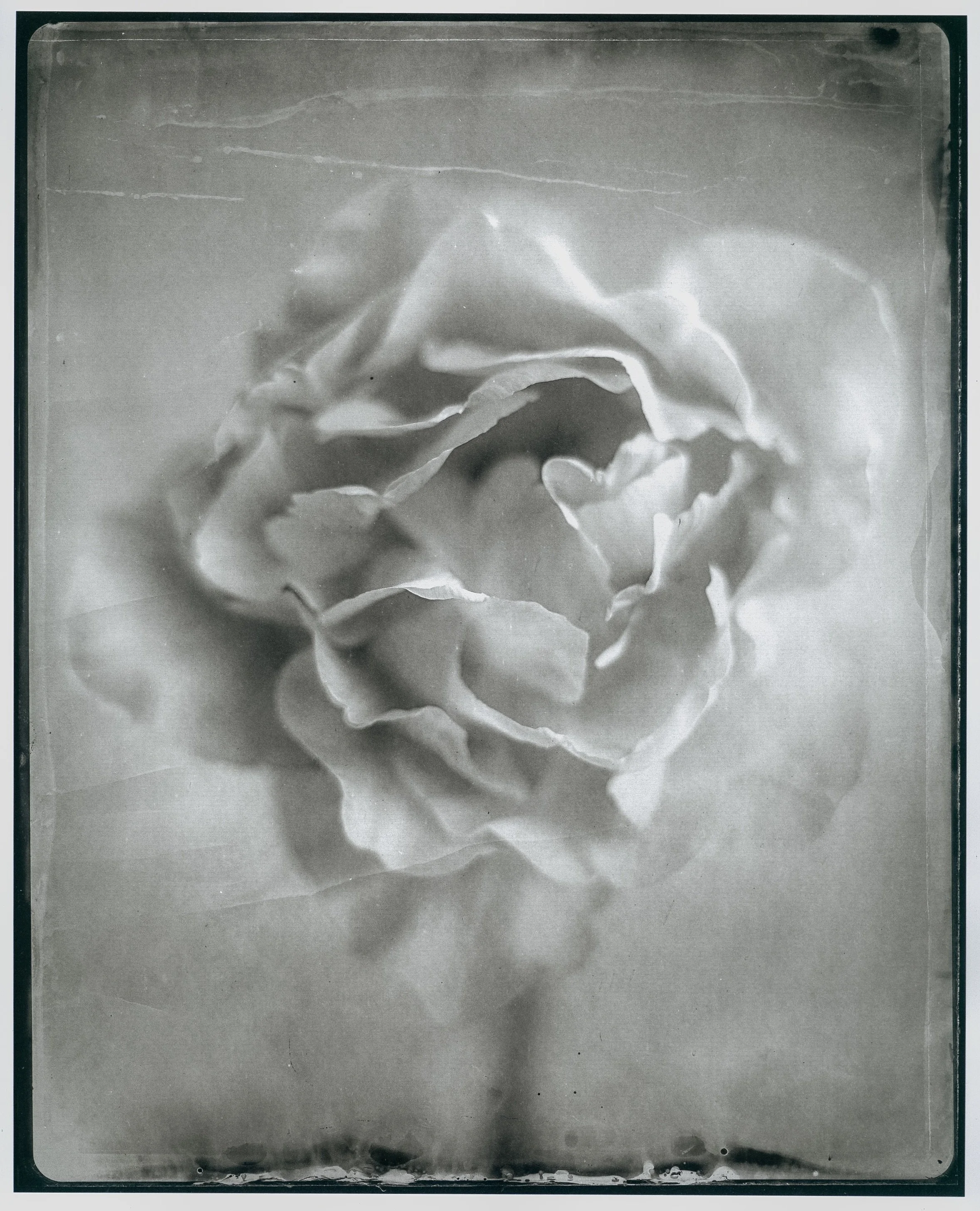

When embarking on a new project or series, I immerse myself fully in the journey. For the phytoplankton series, this meant delving into the intricacies of microscopy and, more importantly, comprehending the essence of the subjects I want to portray.

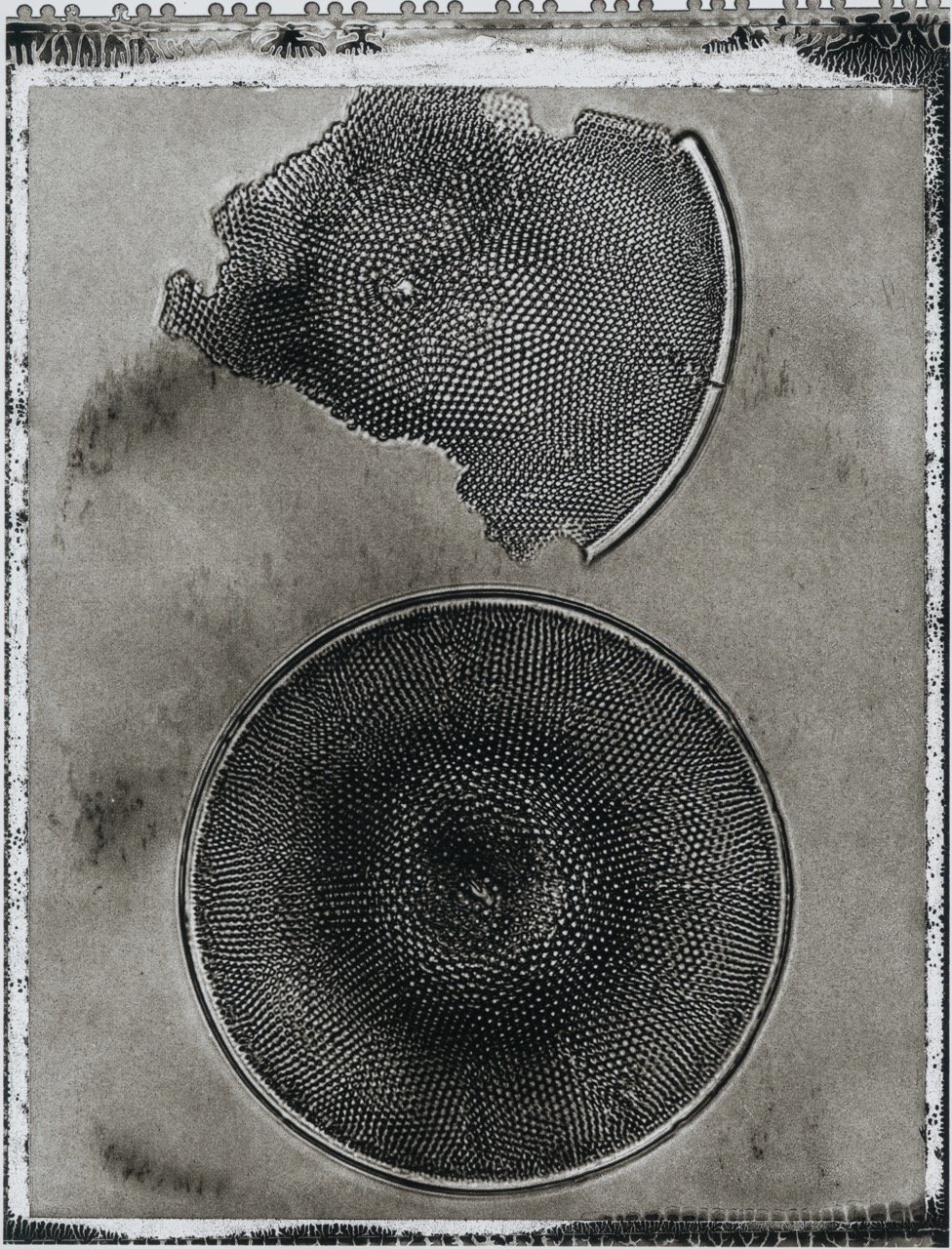

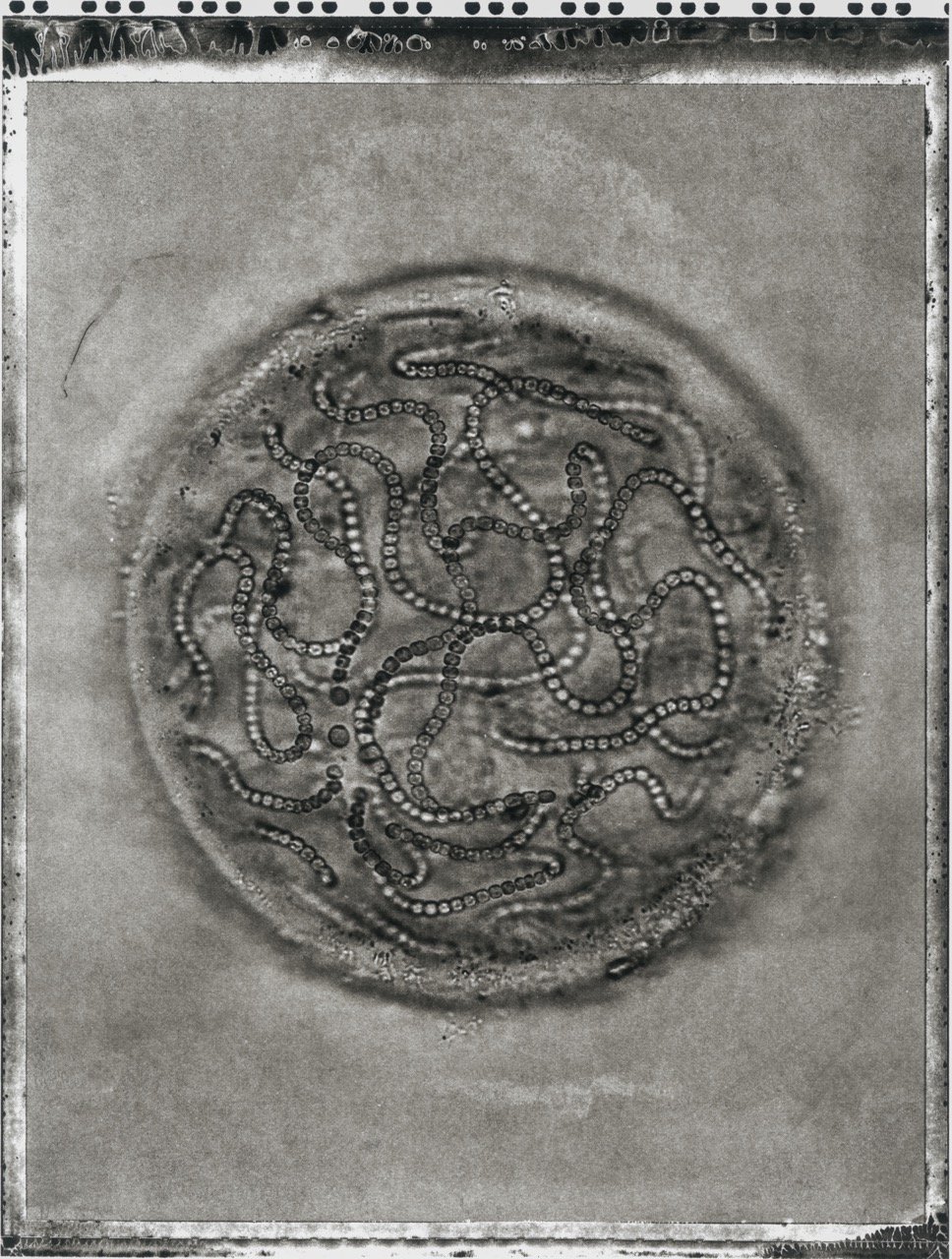

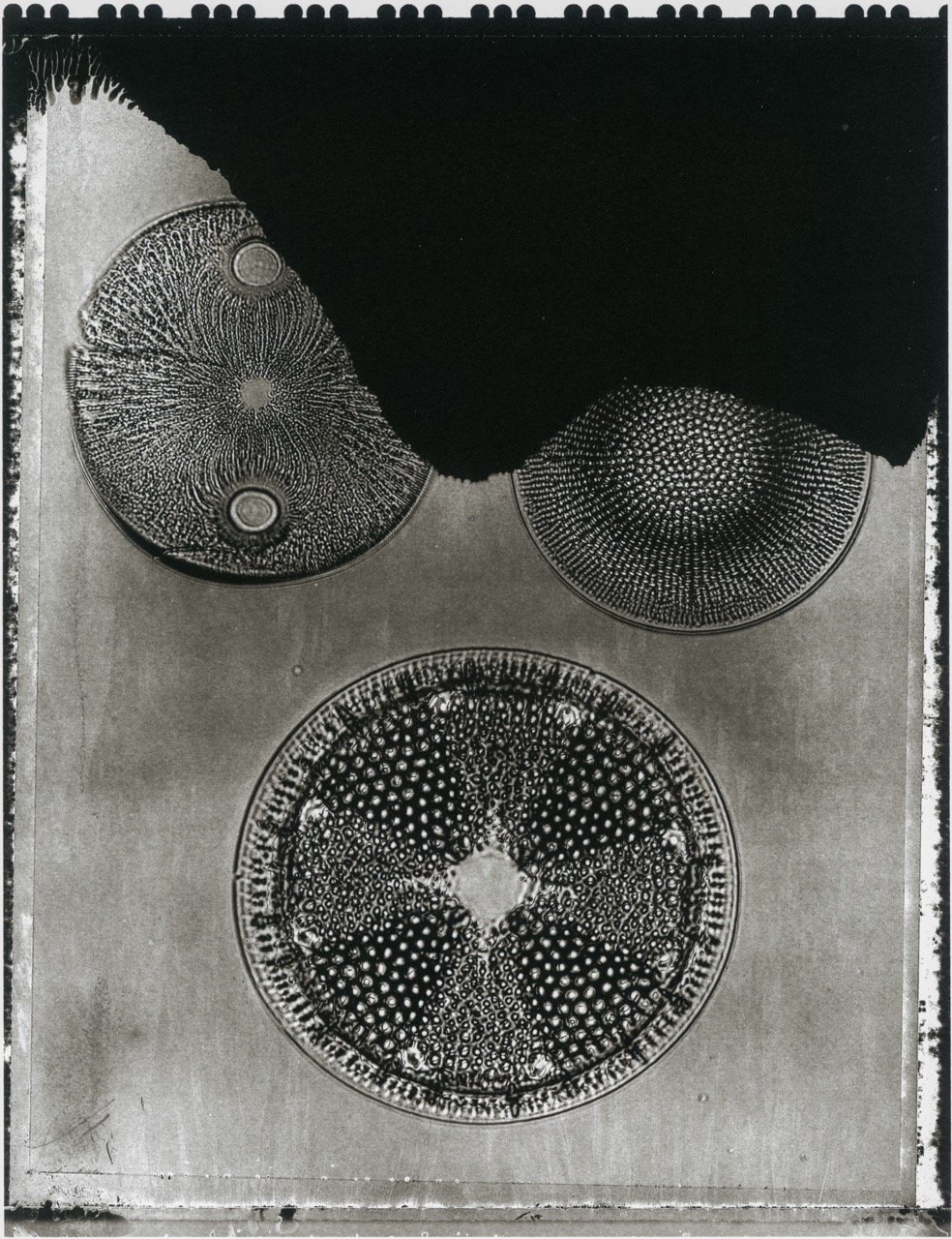

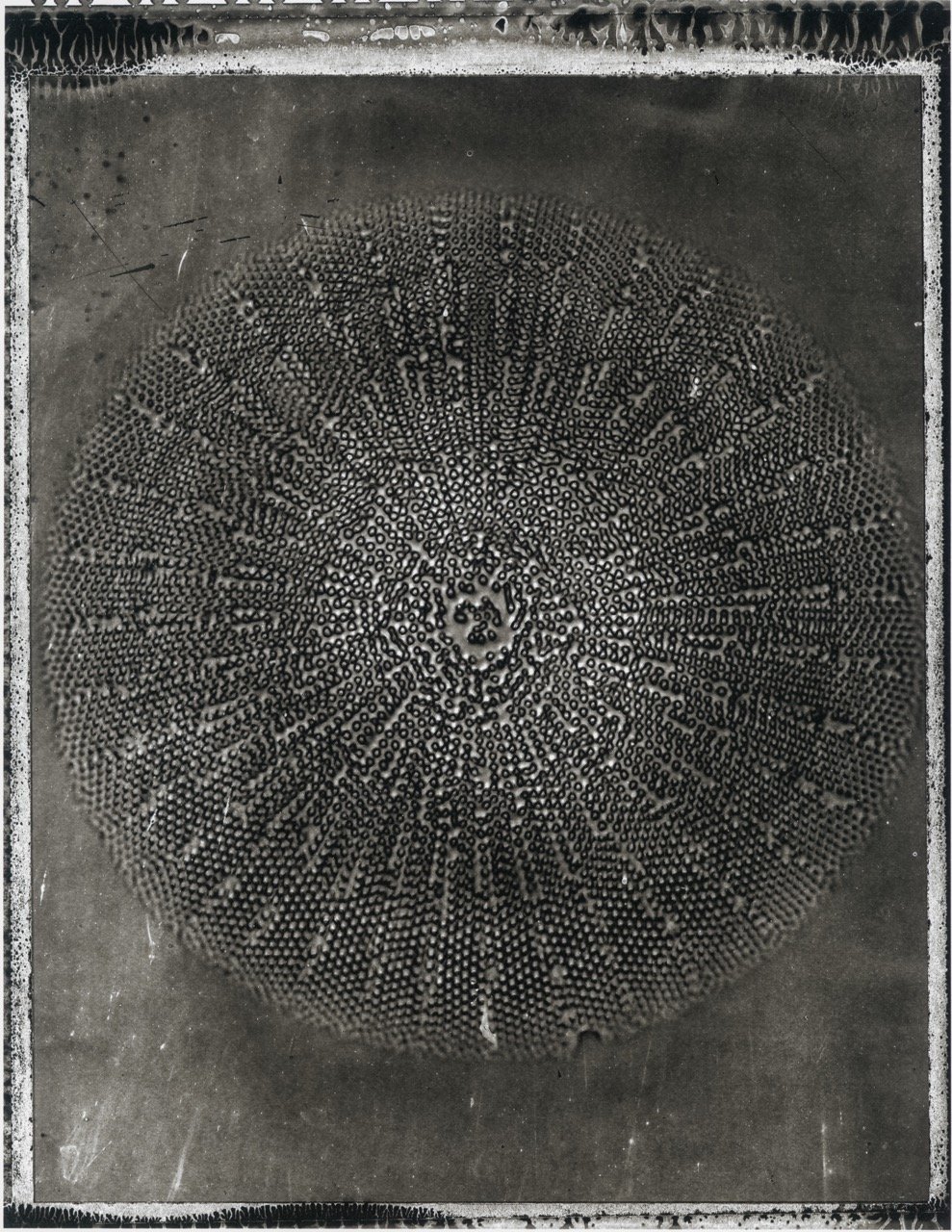

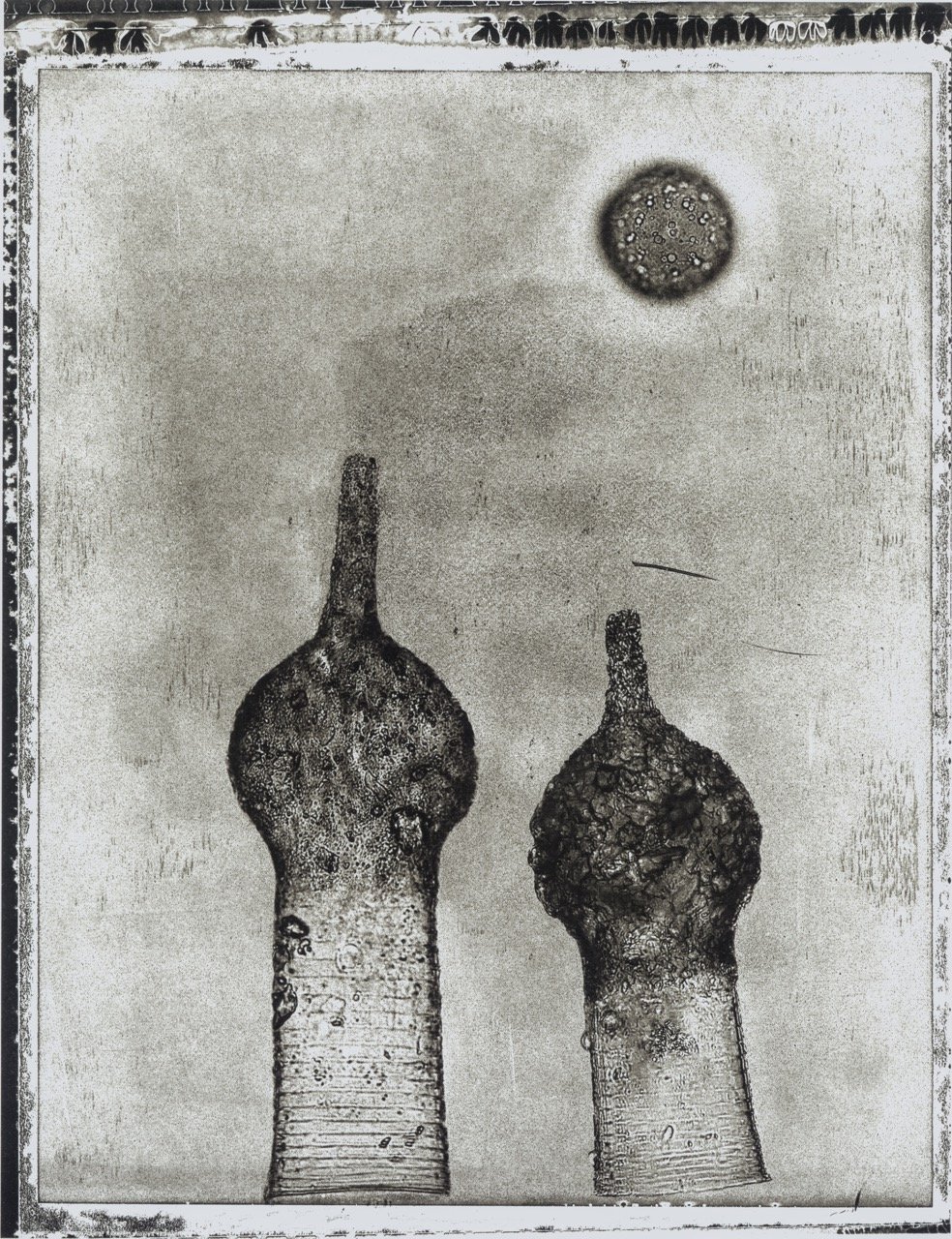

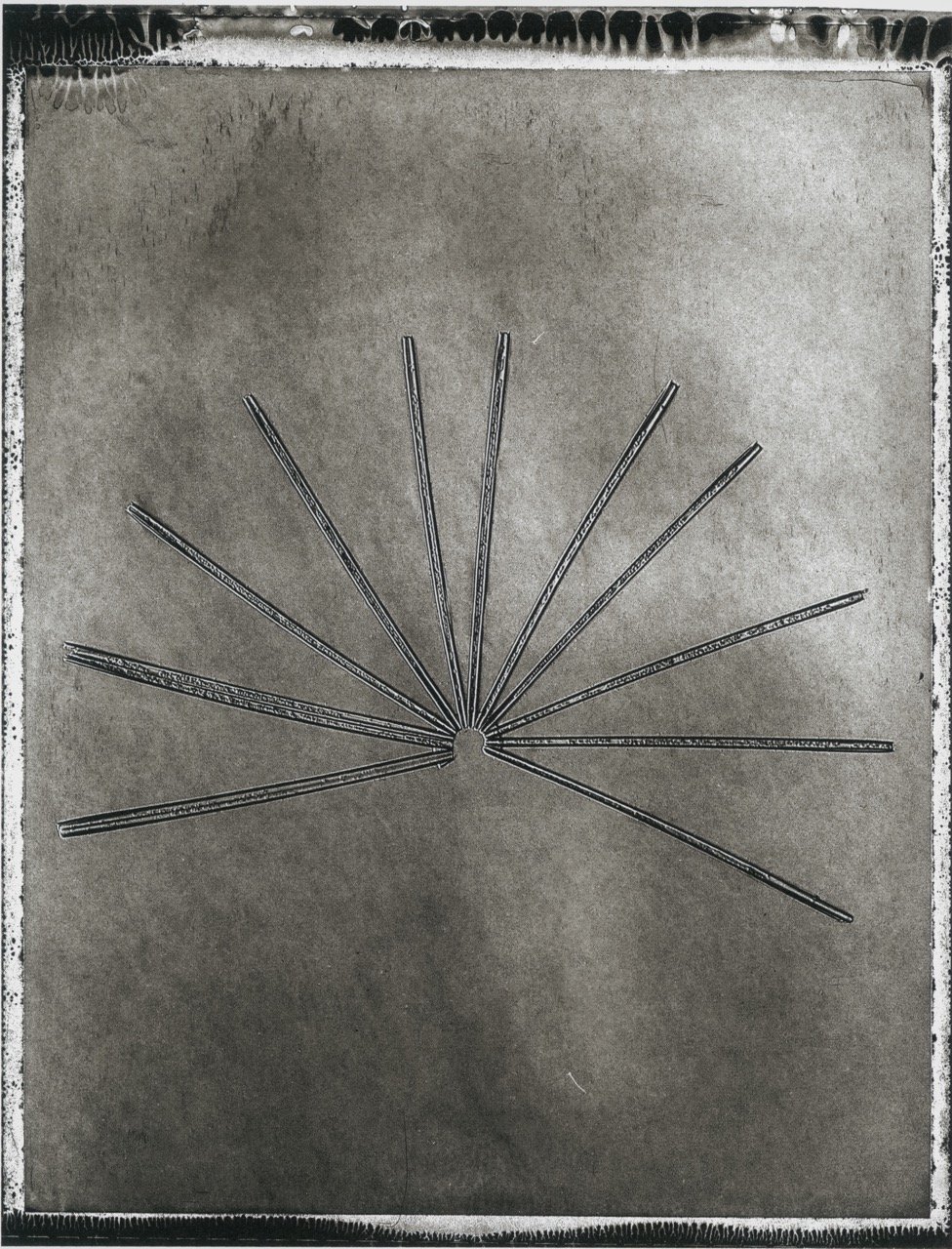

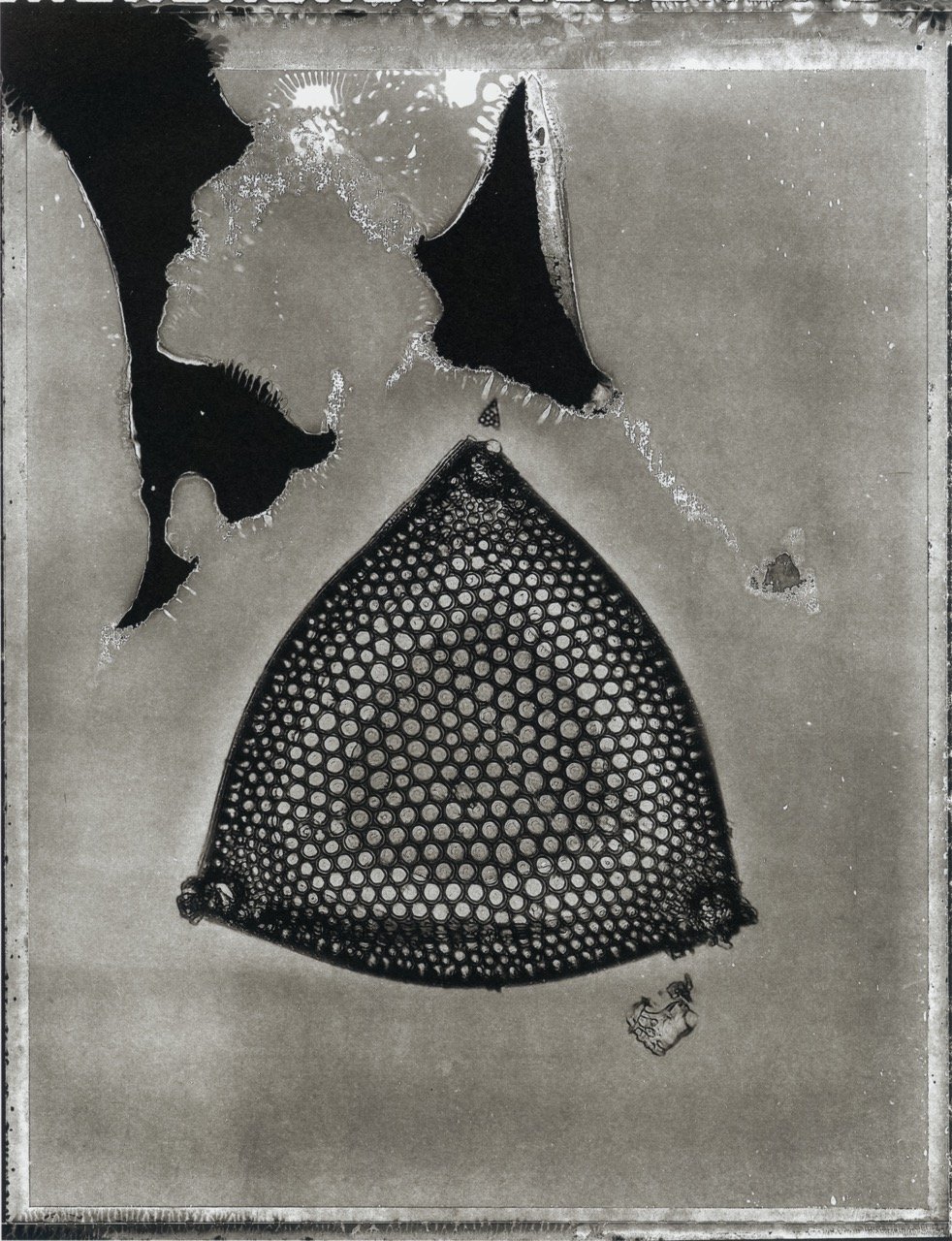

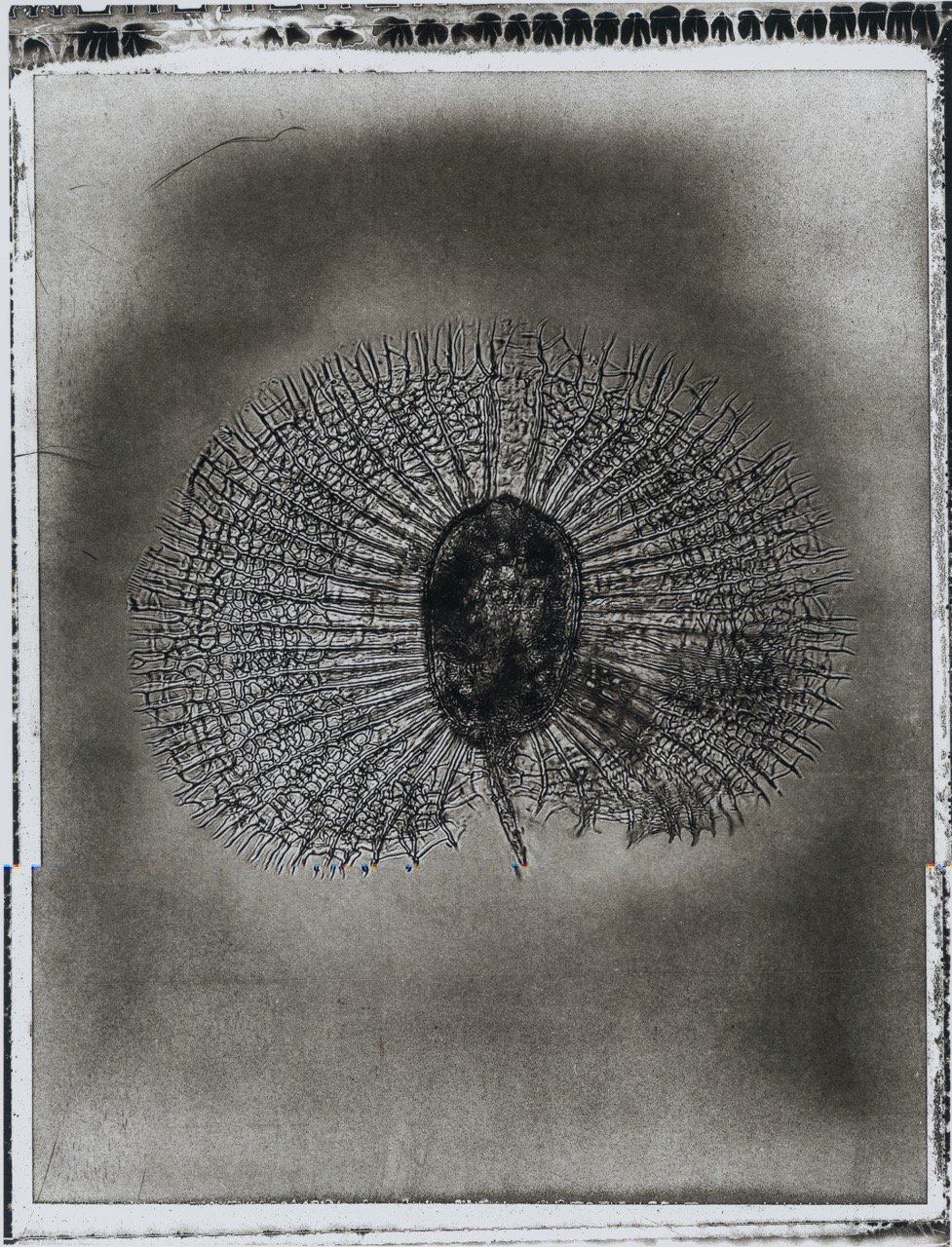

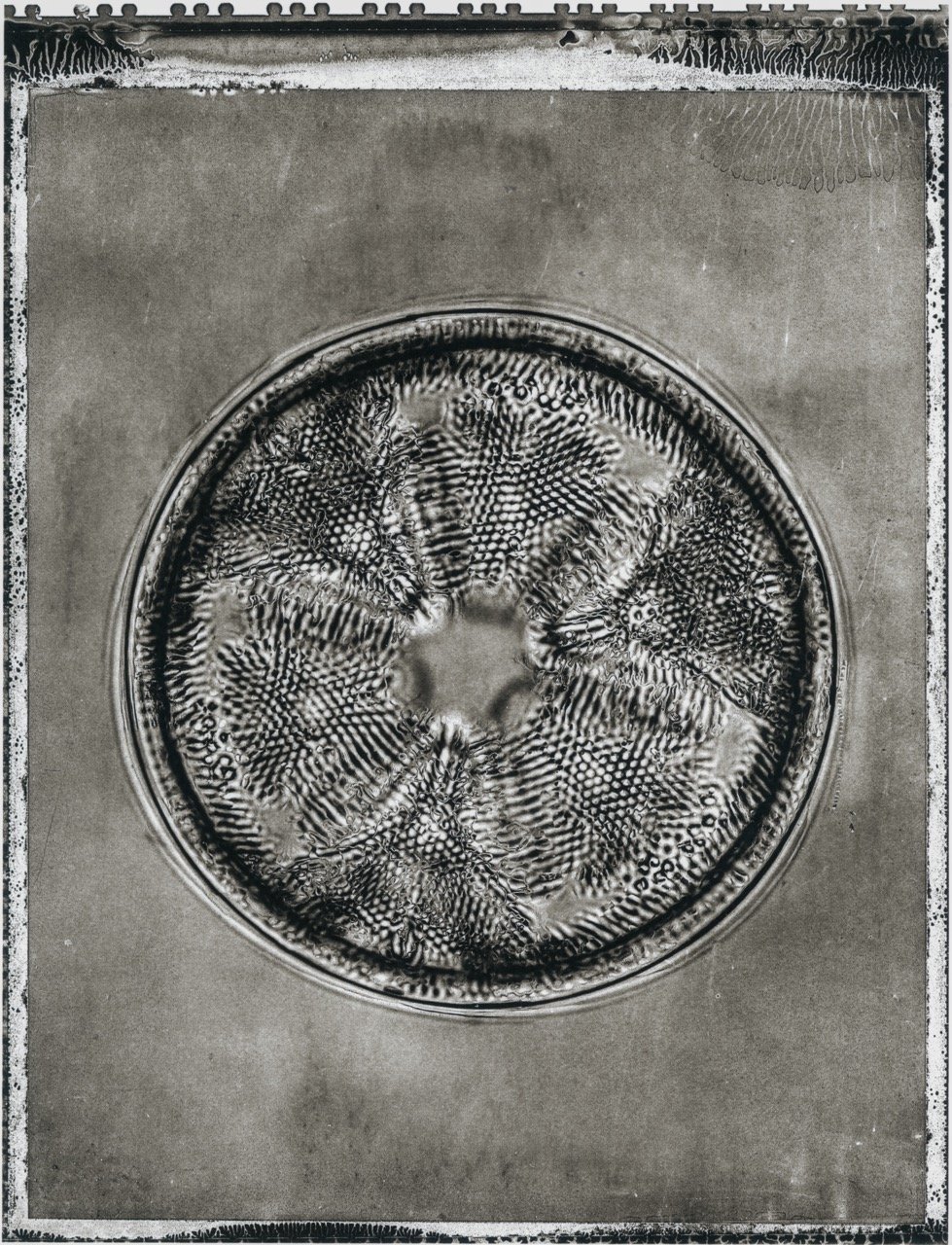

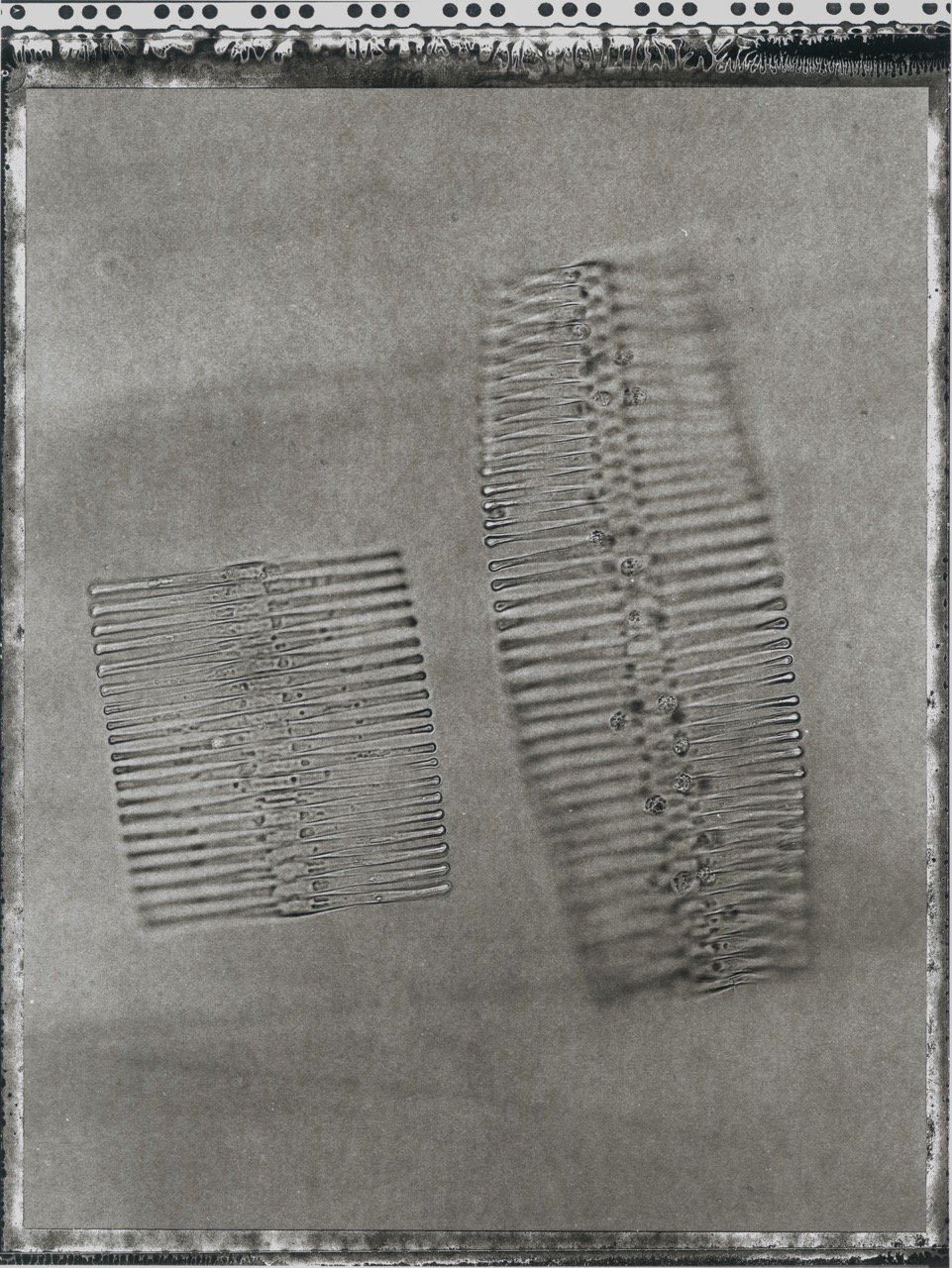

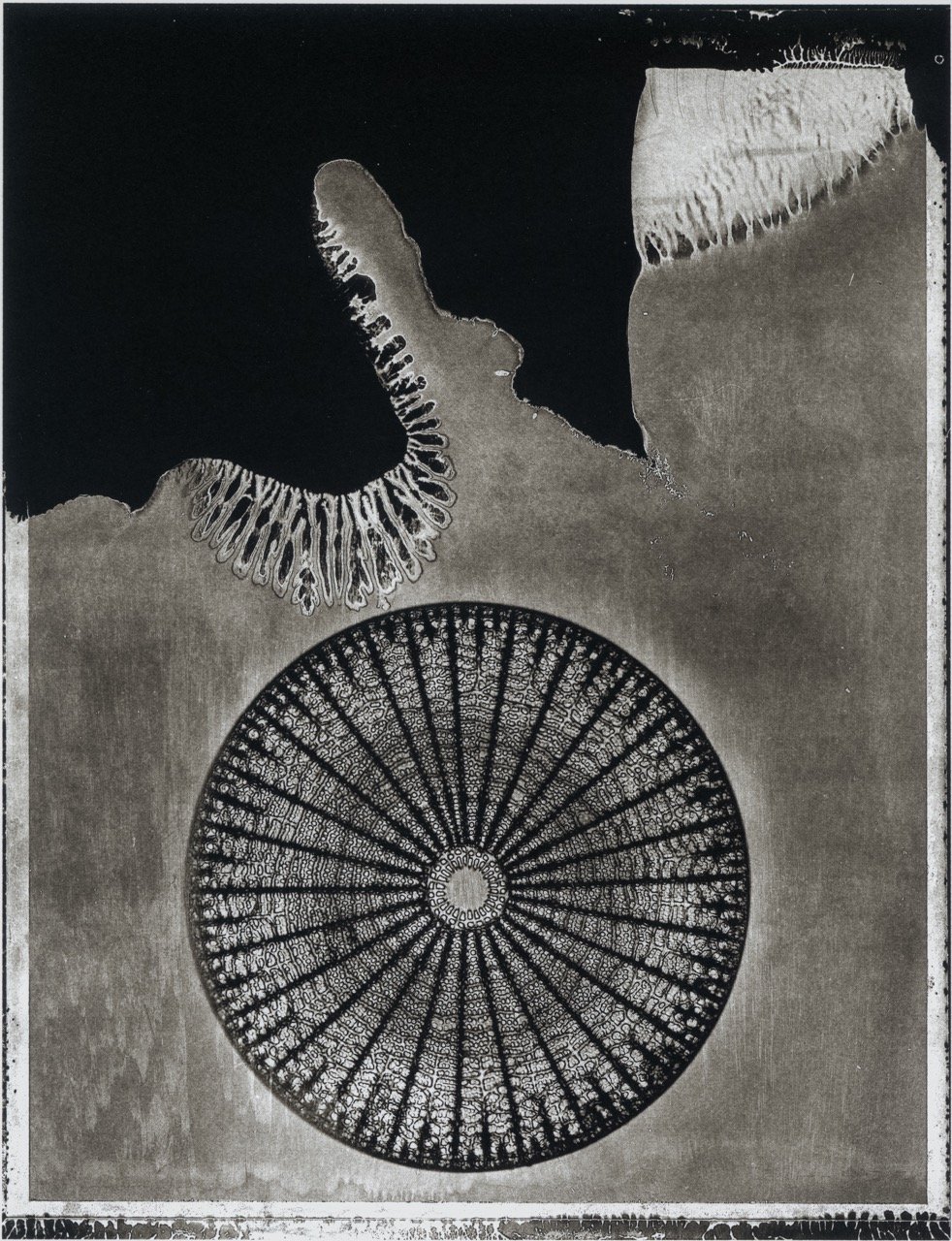

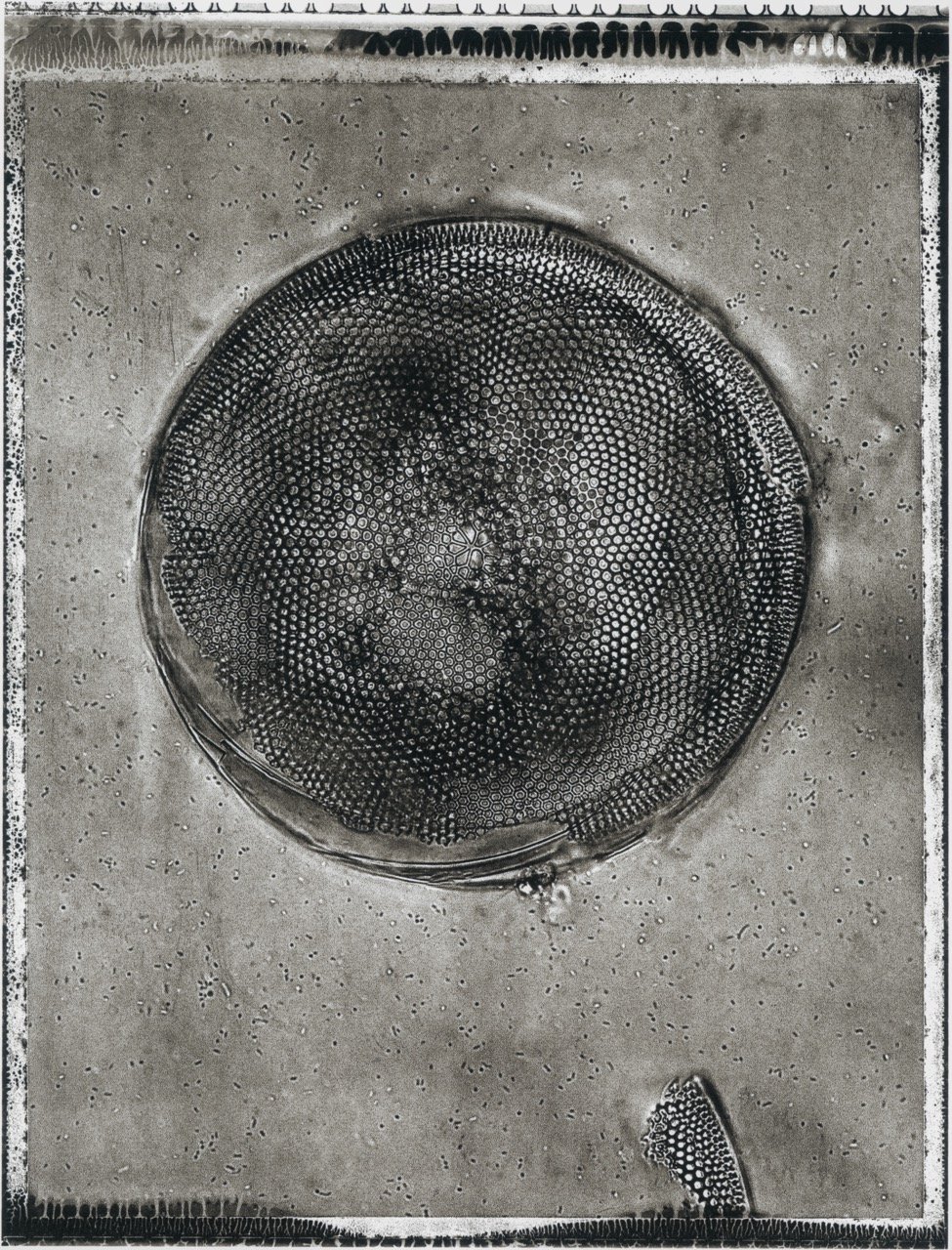

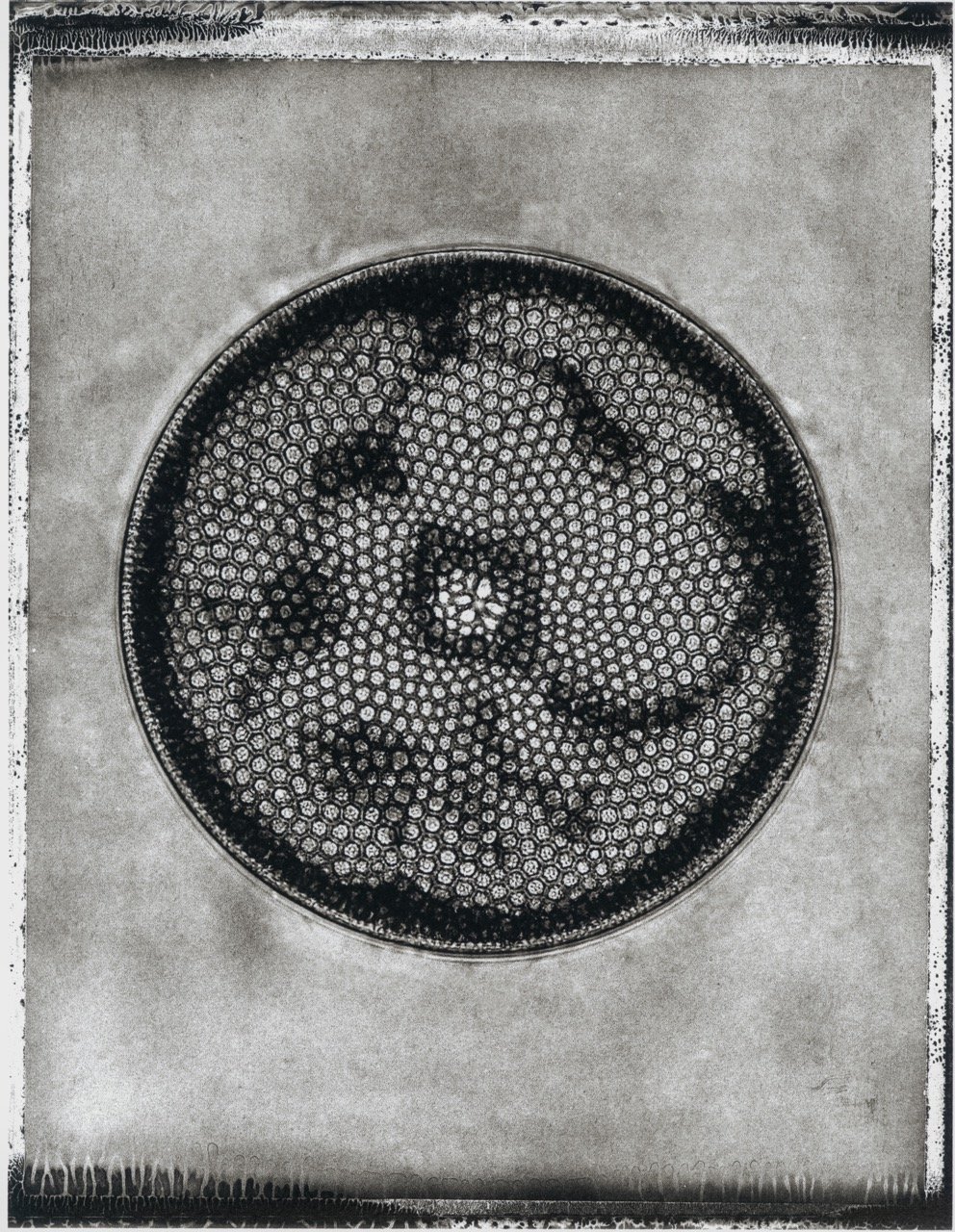

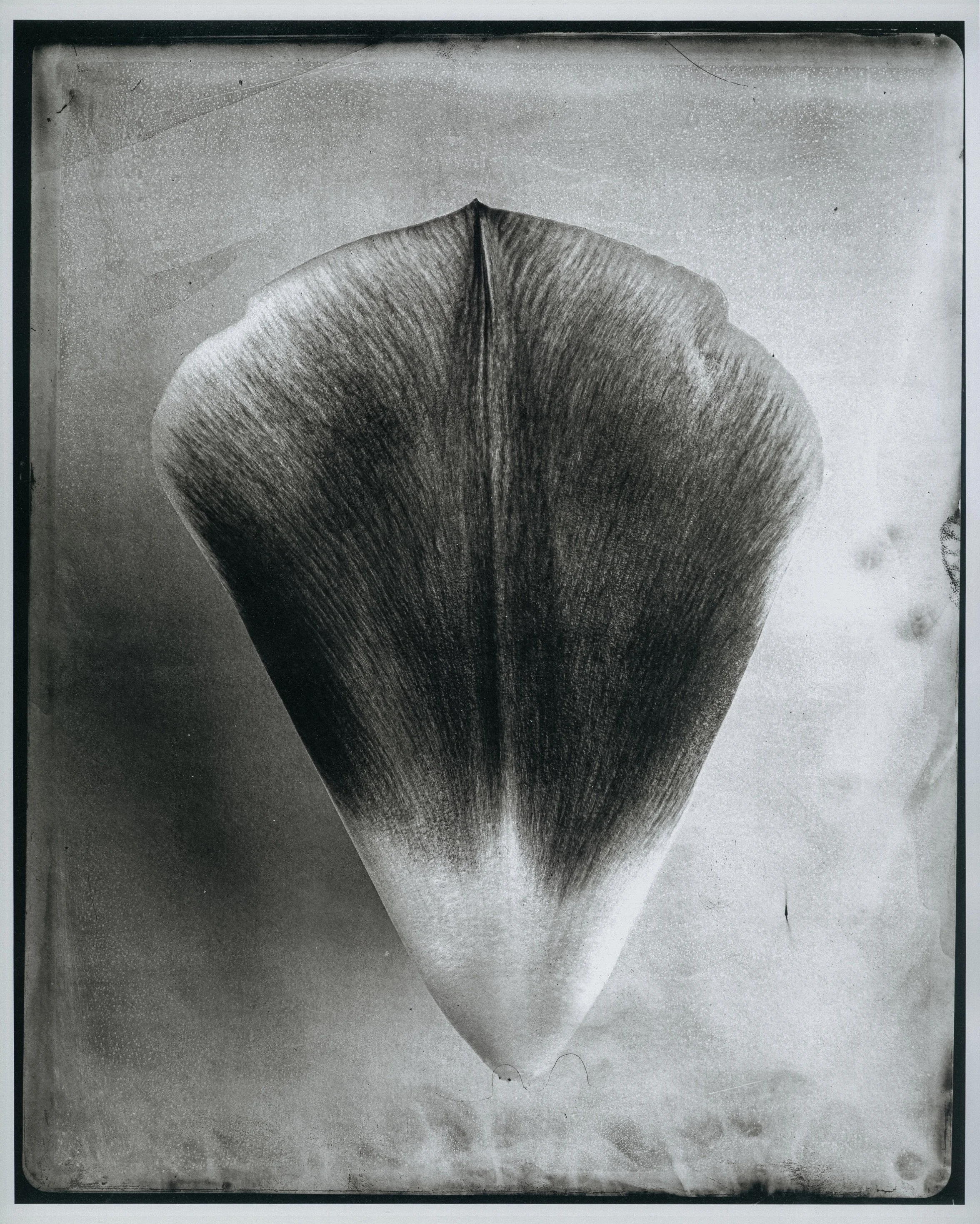

I spend many hours looking through my microscope not only to see something but to comprehend this view's meaning. I wanted to focus on the beauty of this largely unseen world of plant-based plankton rather than allow a by-product of this to turn into a severe science project. Thus, I tried to provide these little but essential organisms with a giant megaphone and draw people's attention to their role in our world.

The project was a personal discovery of the most fundamental basis of life. Discovering and seeing these microscopical beings, reading about them, and studying them altered how I look at the world.

I soon realized just how vital phytoplankton are. They are at the lowest levels of the planet's food chain and are indispensable for our climate, as they release 50% to 80% of the oxygen we breathe. I also became educated on issues that include microplastic pollution of the oceans, the slowing of the Gulf Stream, heating of the oceans, and the formation of clouds. I did not expect this series to develop into such significant work, and for that, I needed to truly understand what I was trying to show.

Motivated by curiosity and determination, I attempted to create my microcosm in a jar of water and salt. After much effort, I cultivated adequate phytoplankton that grew into a populous colony. And out of that one plankton, I generated a plankton bloom of bioluminescent specimens seen from my trip to Thailand. Their glitter made my jar look like an enchanting spectacle. Just a shake, and out came the beautiful, magical blue light.

This project took me more than two years of research, and I traveled to numerous oceans, including the South China Sea, the North Atlantic, the South Pacific, the Mediterranean Sea, the Black Sea, the Caribbean Sea, and many more. Therefore, I aimed to provide a broad outlook on phytoplankton. With my plankton net, I went to more than 20 locations where I hired a boat and towed the plankton net behind me, filling many bottles of water with the leftovers of the net, without knowing what I would discover at home while looking through the ocular of my microscope.

In retrospect, I was privileged to create the series. The beauty, mystery, and wonders revealed by using the microscope helped me transform and gave me a new perspective on this world. Now, I have the privilege of showcasing the 48 prints of the series as well as the personal research and study that has taken place, which informs the work about phytoplankton.

I would like to express my gratitude for all the support, encouragement, and skilled assistance I have received during the past two years as I realized the series.

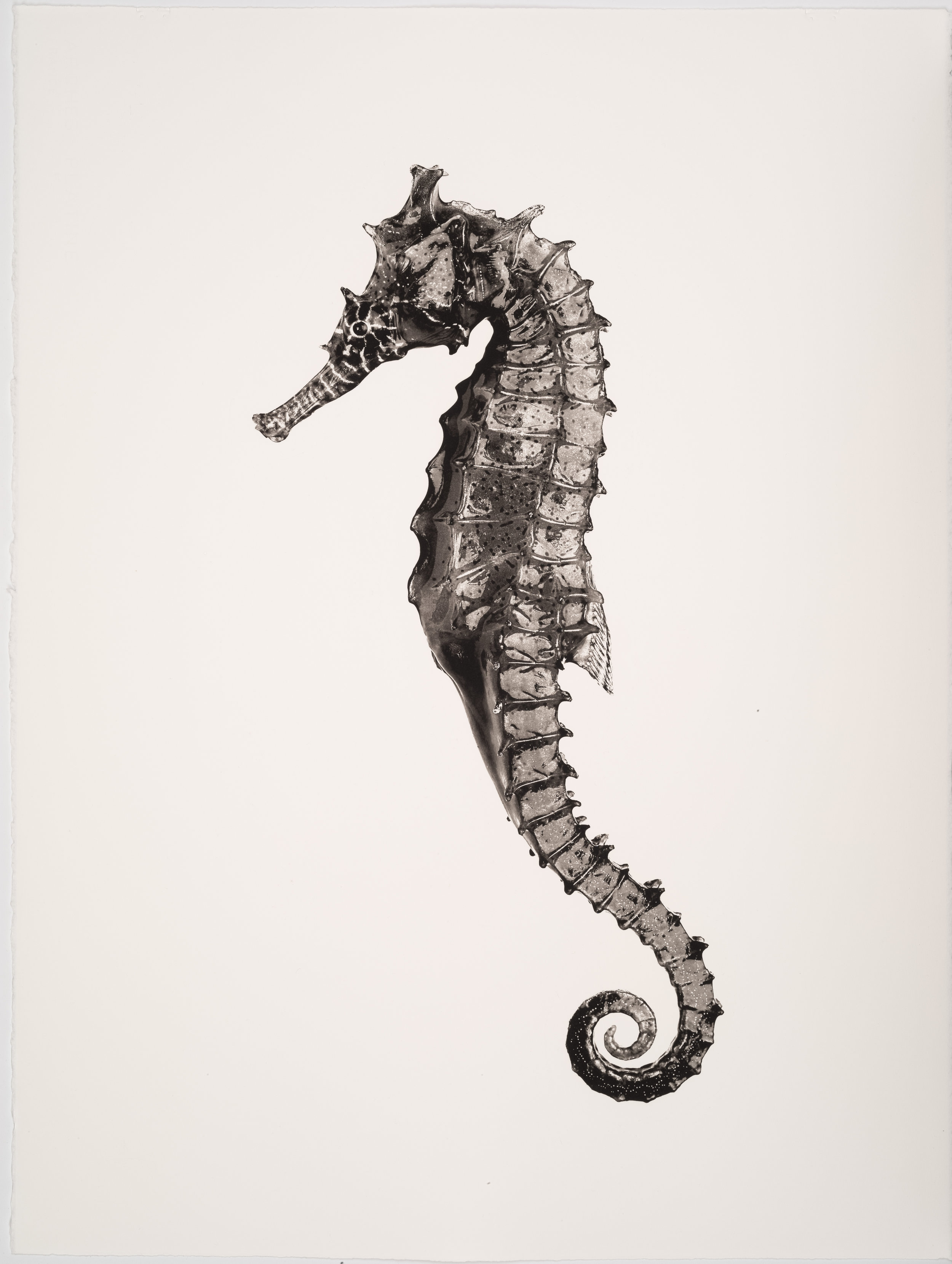

AT THE BEGINNING

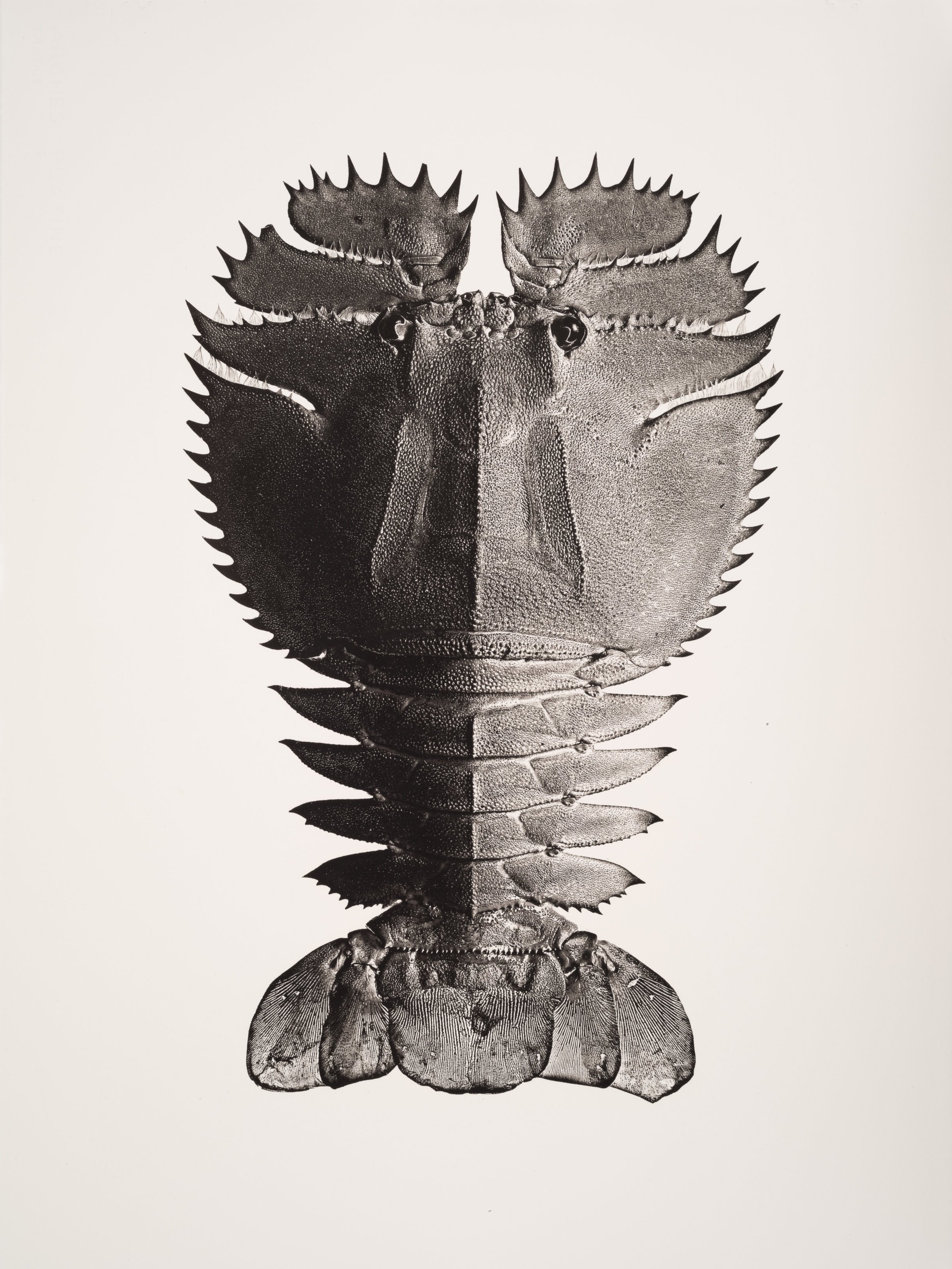

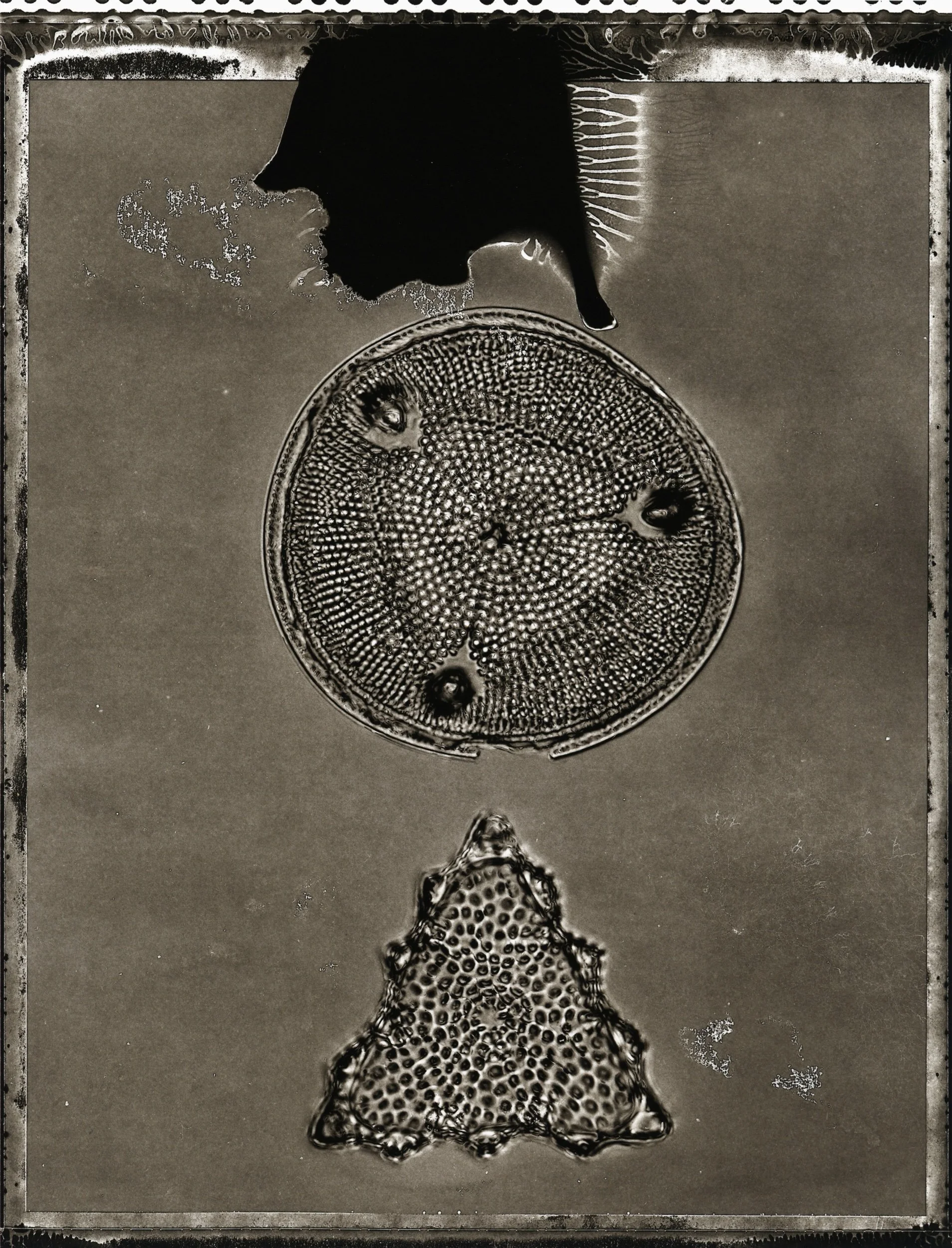

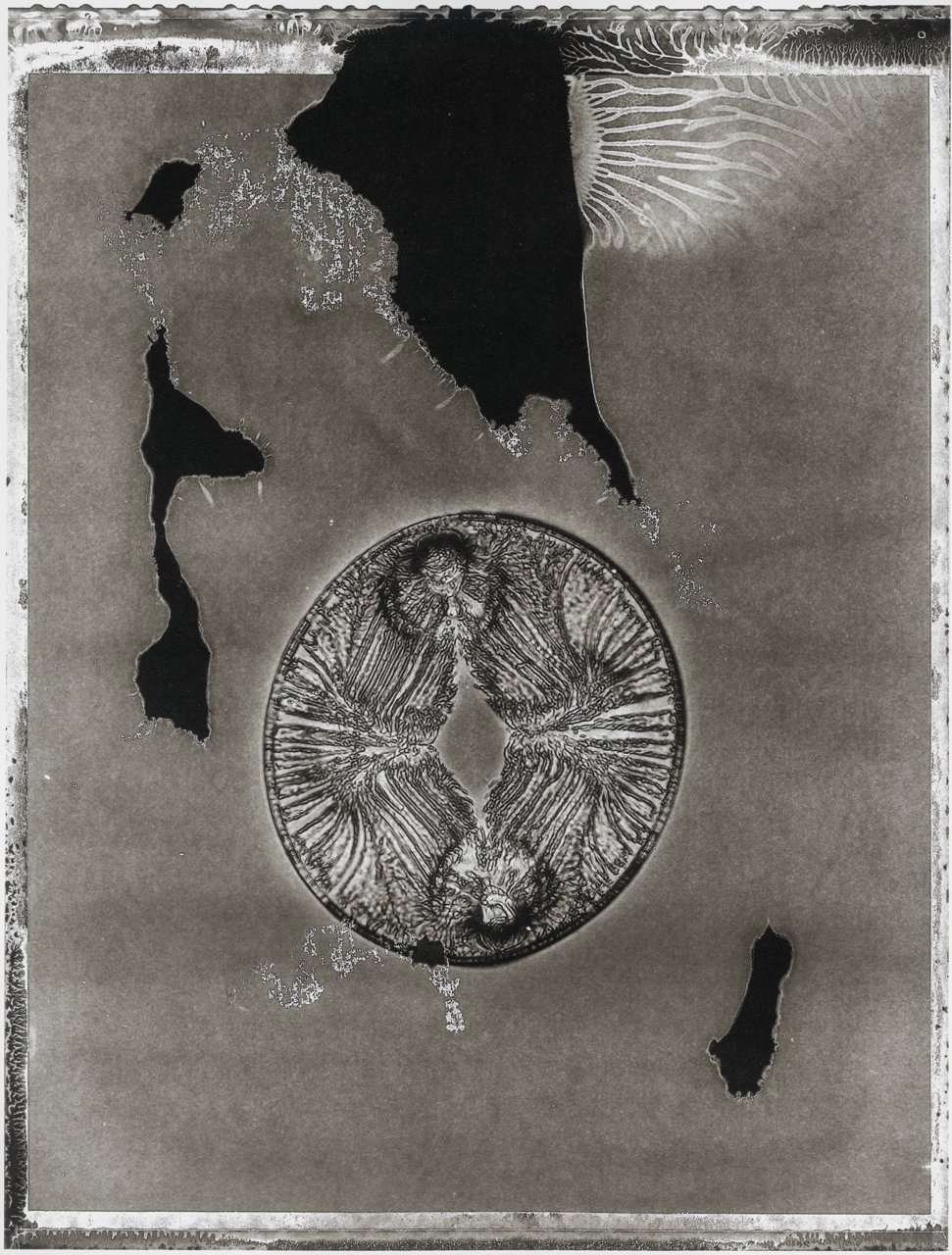

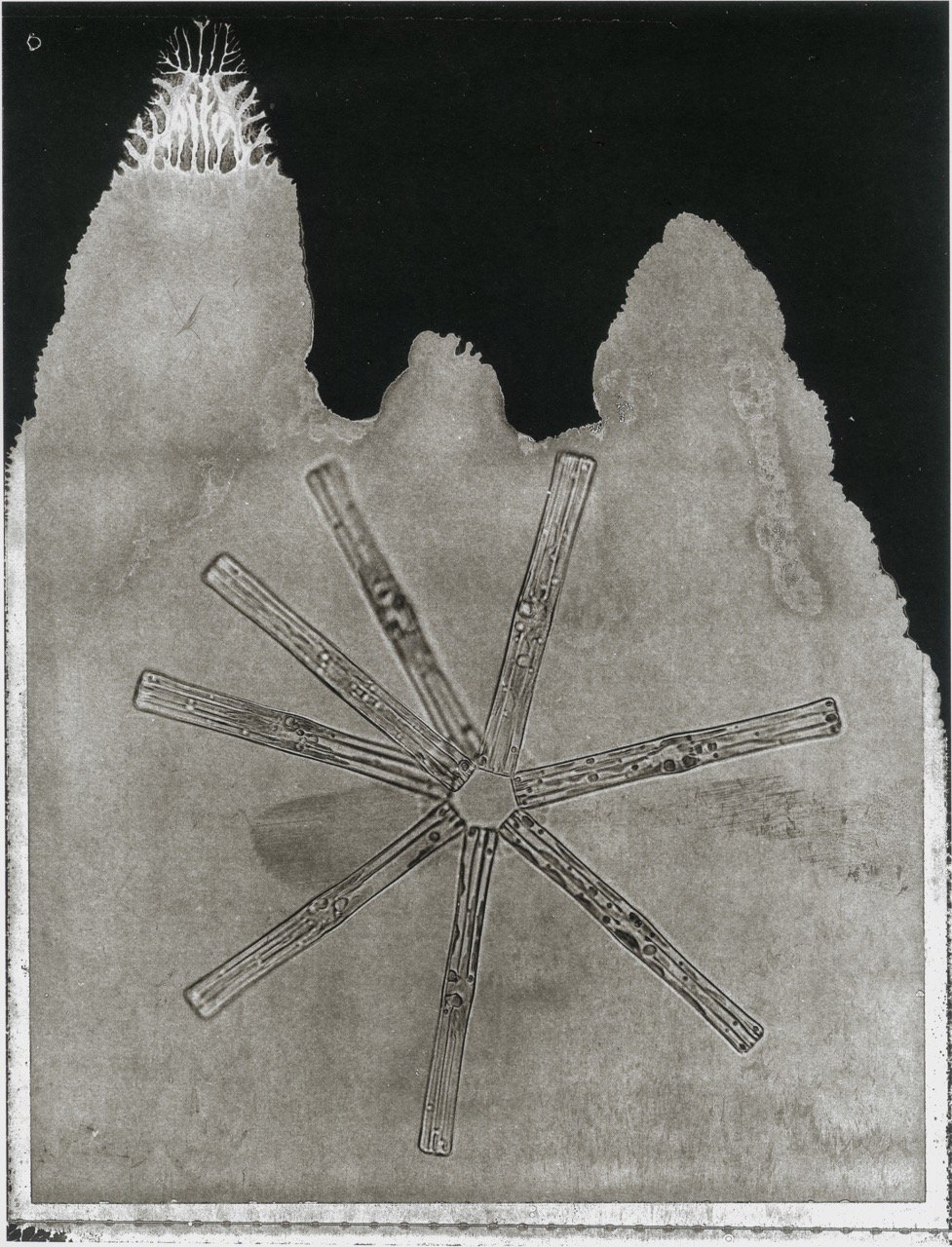

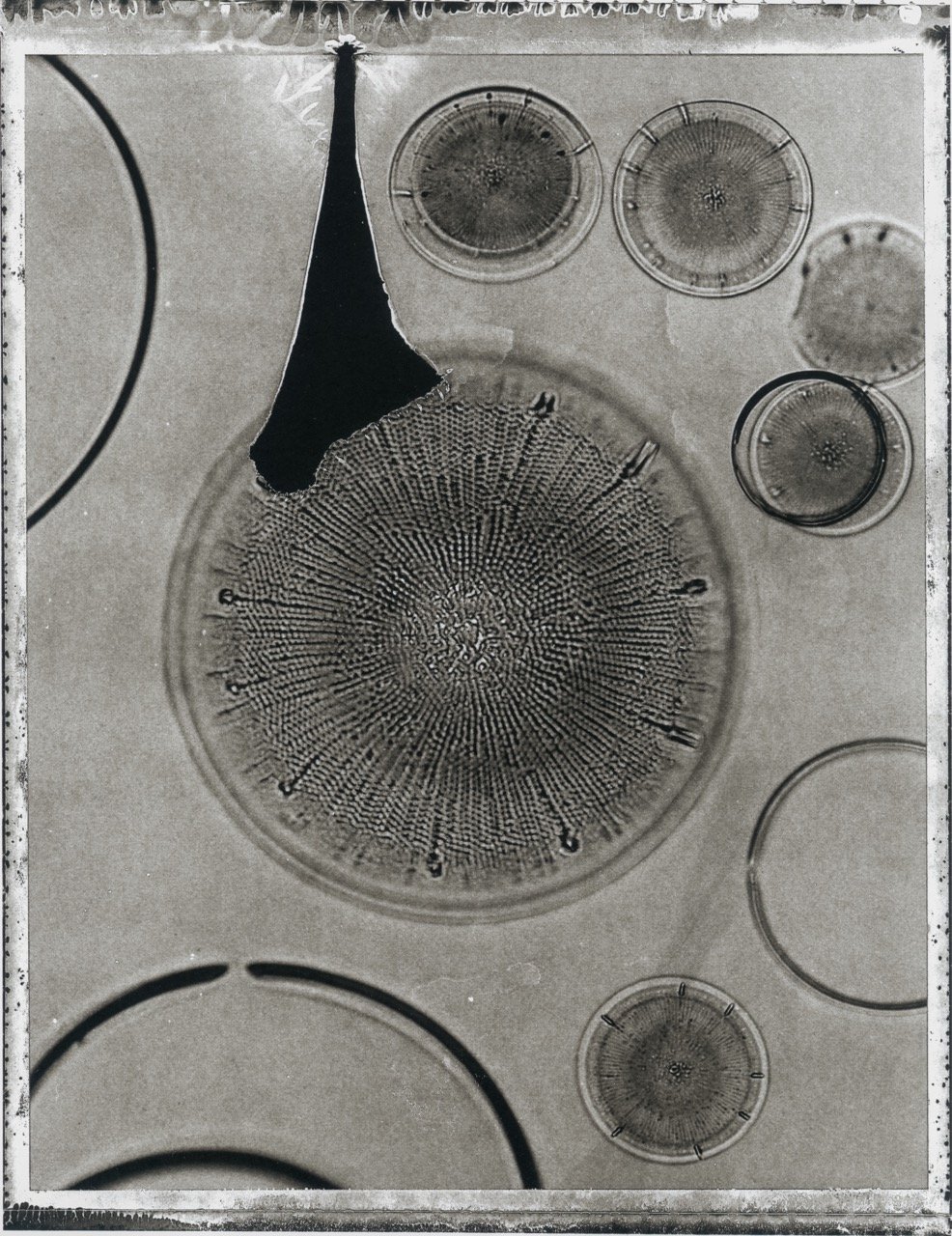

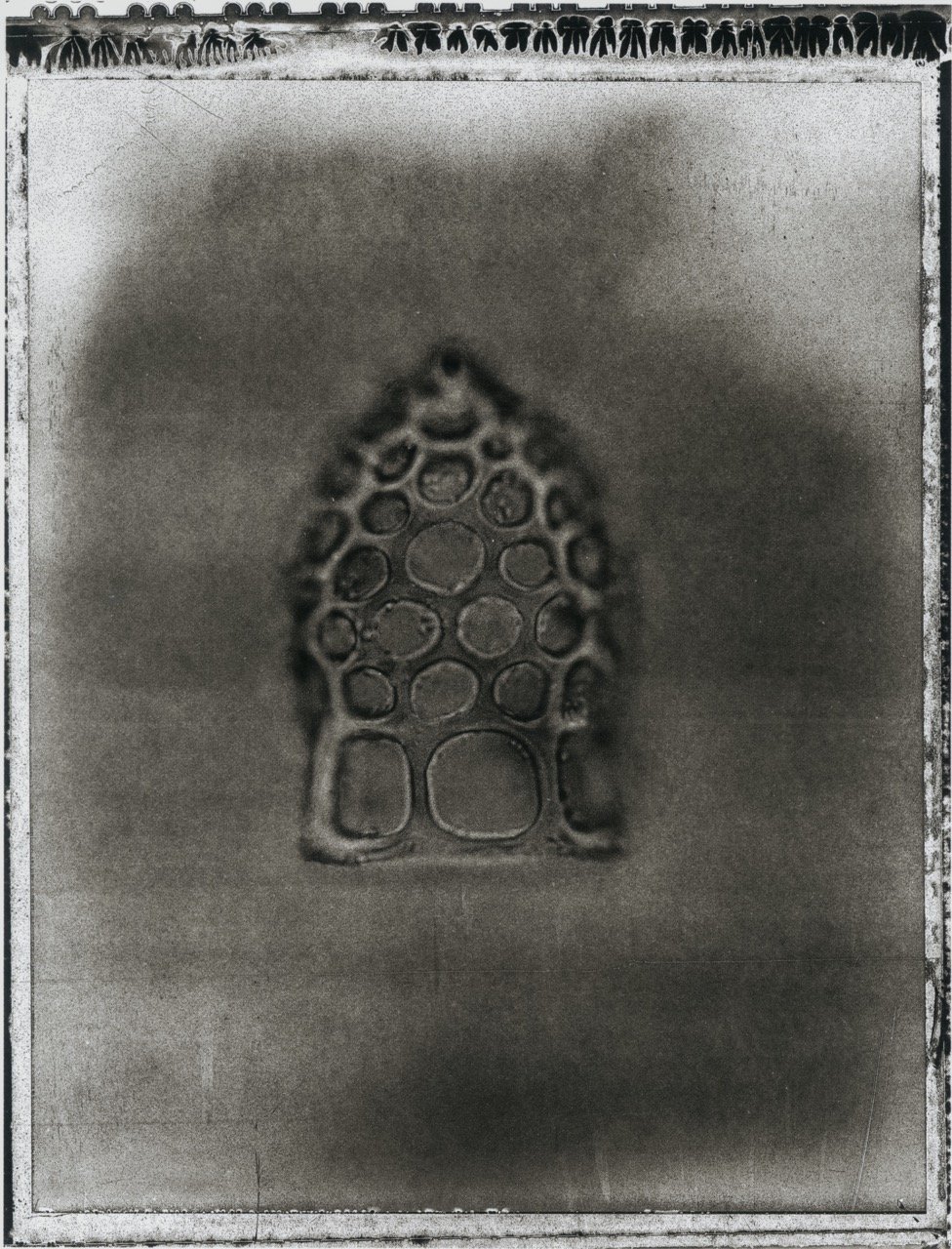

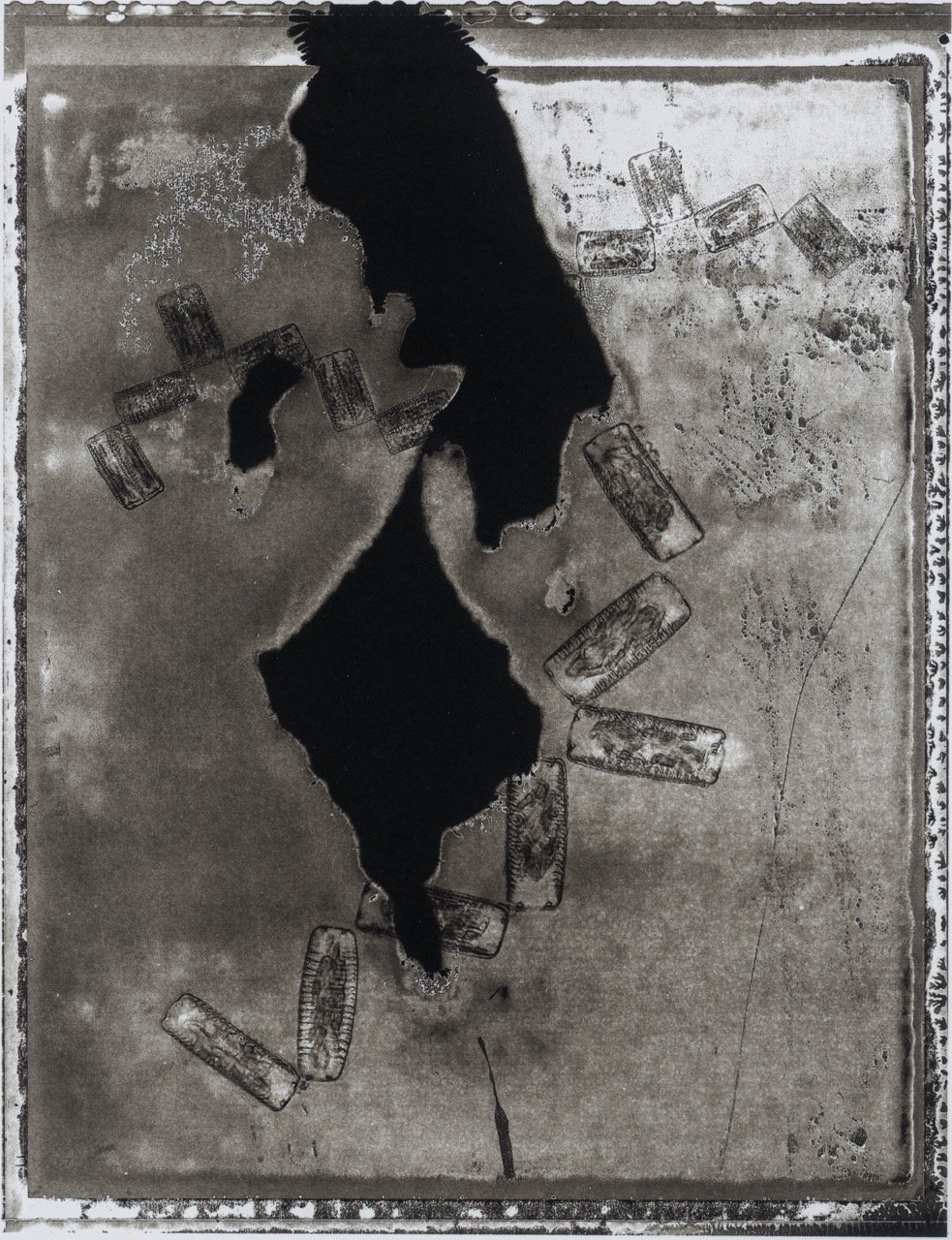

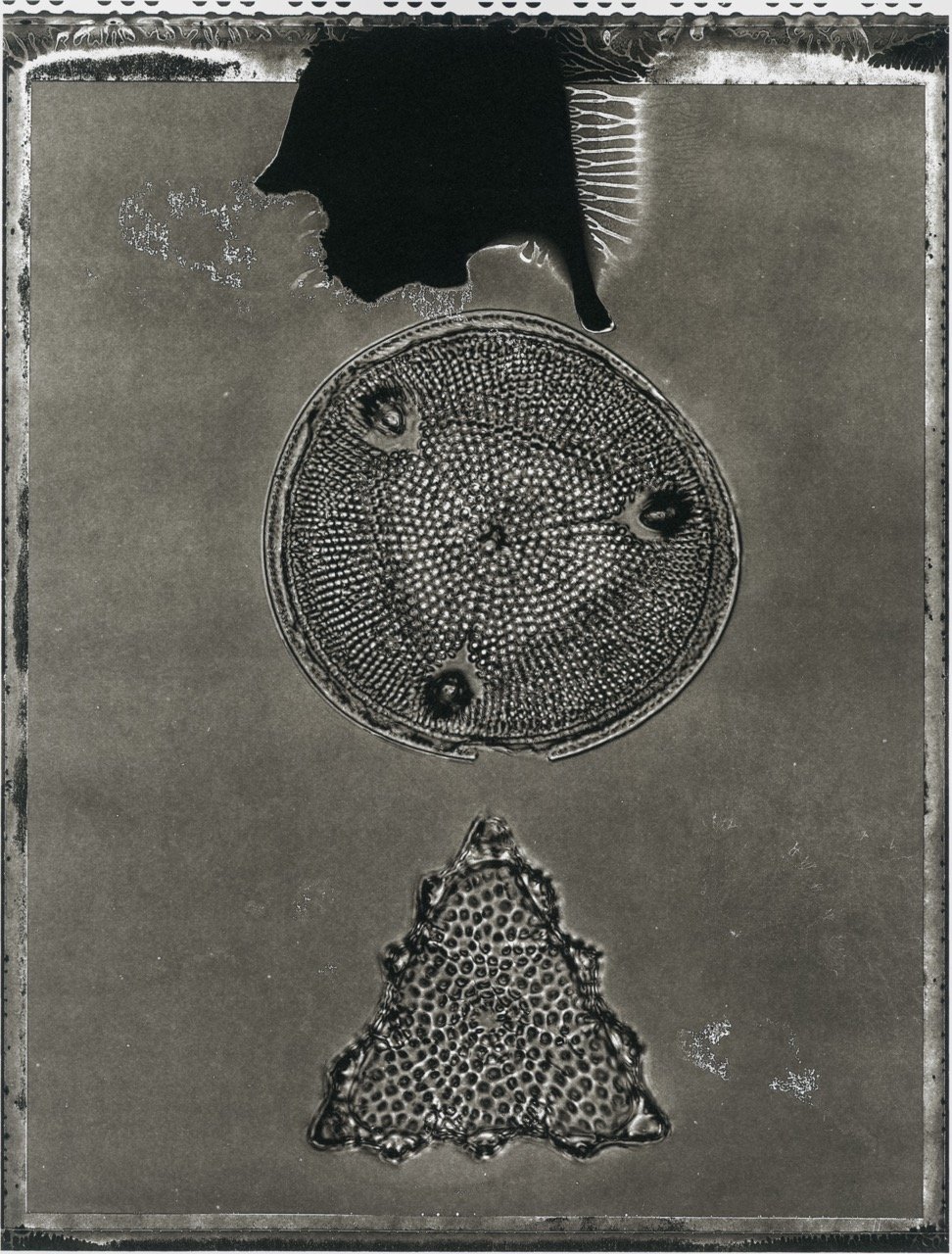

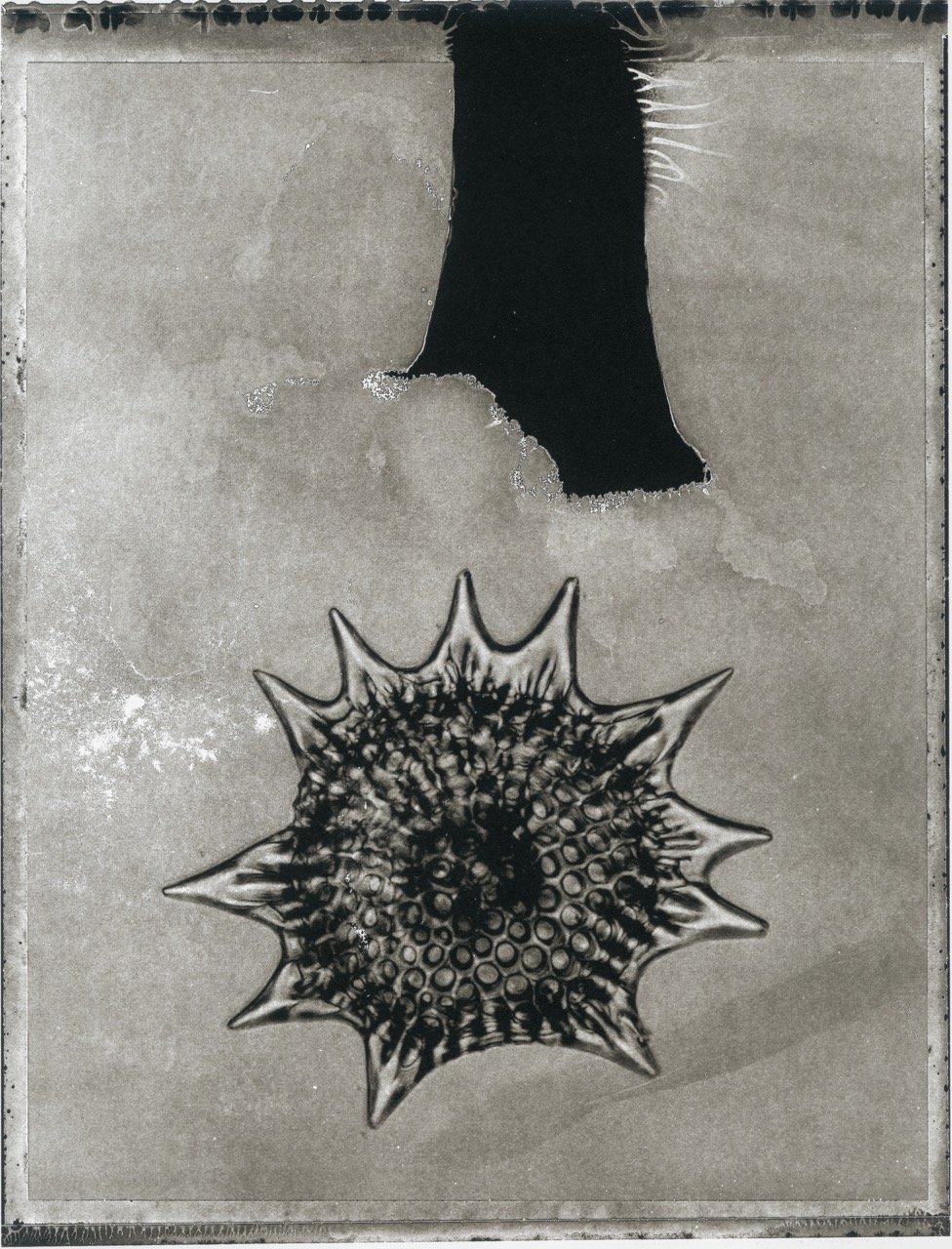

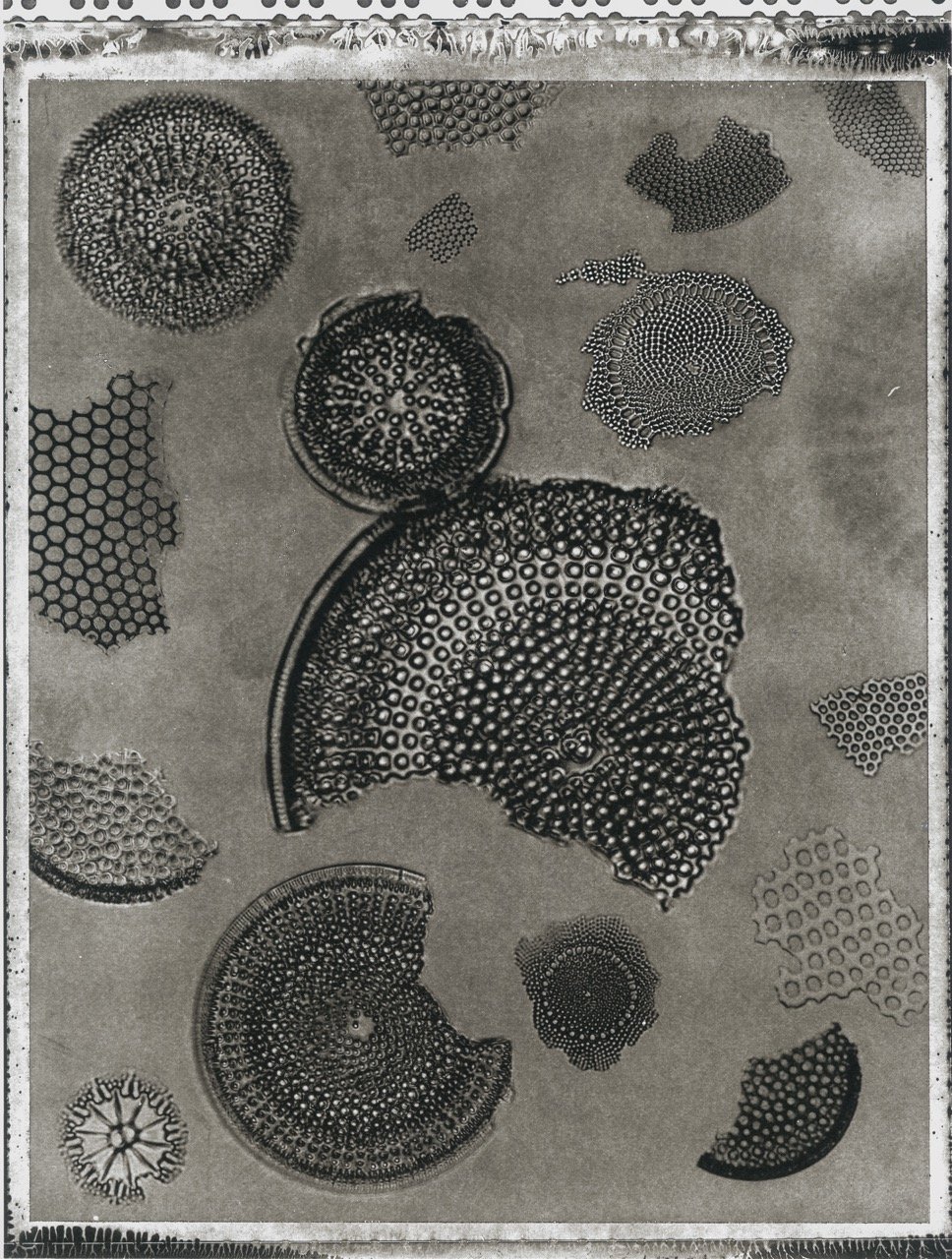

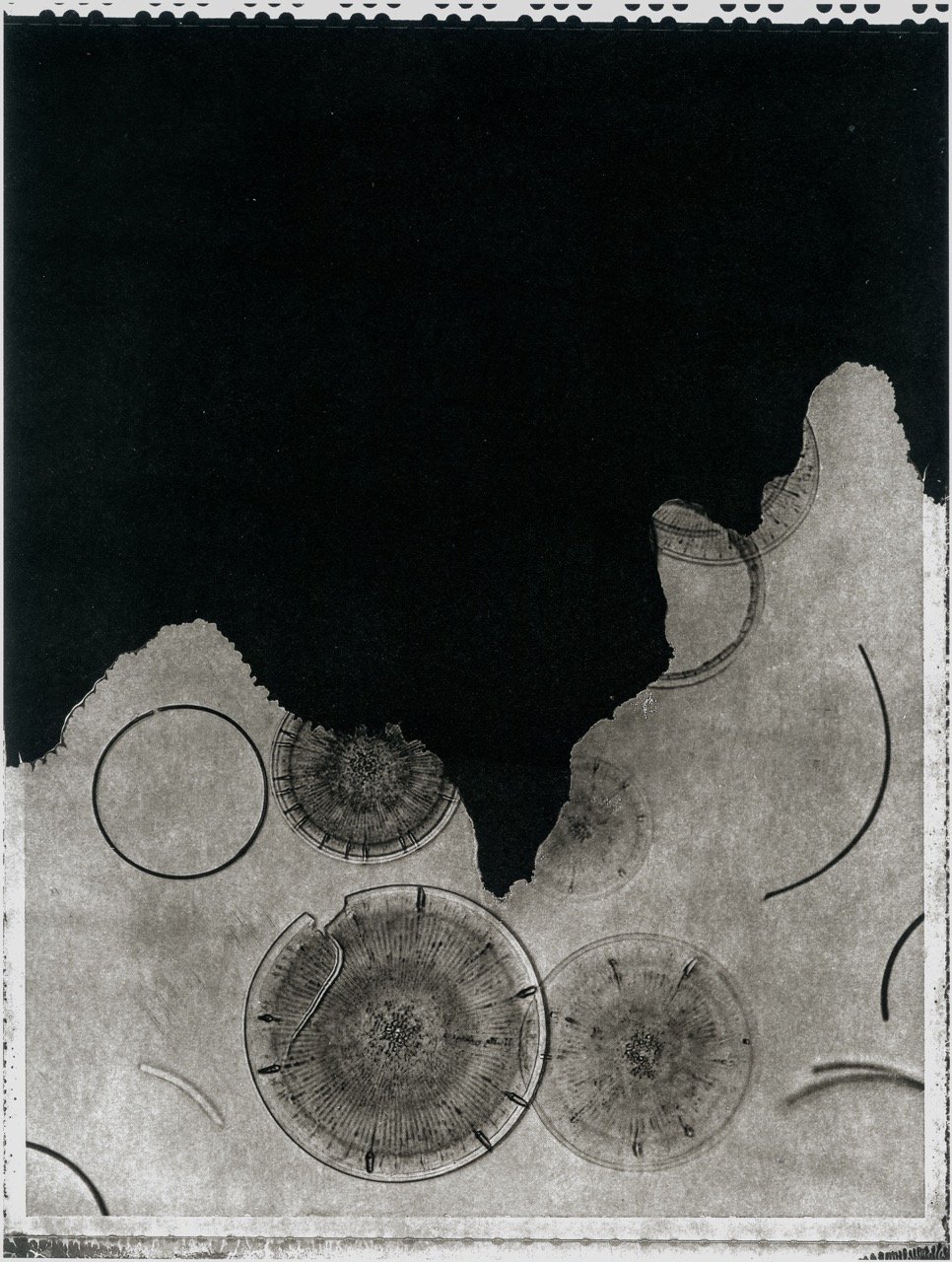

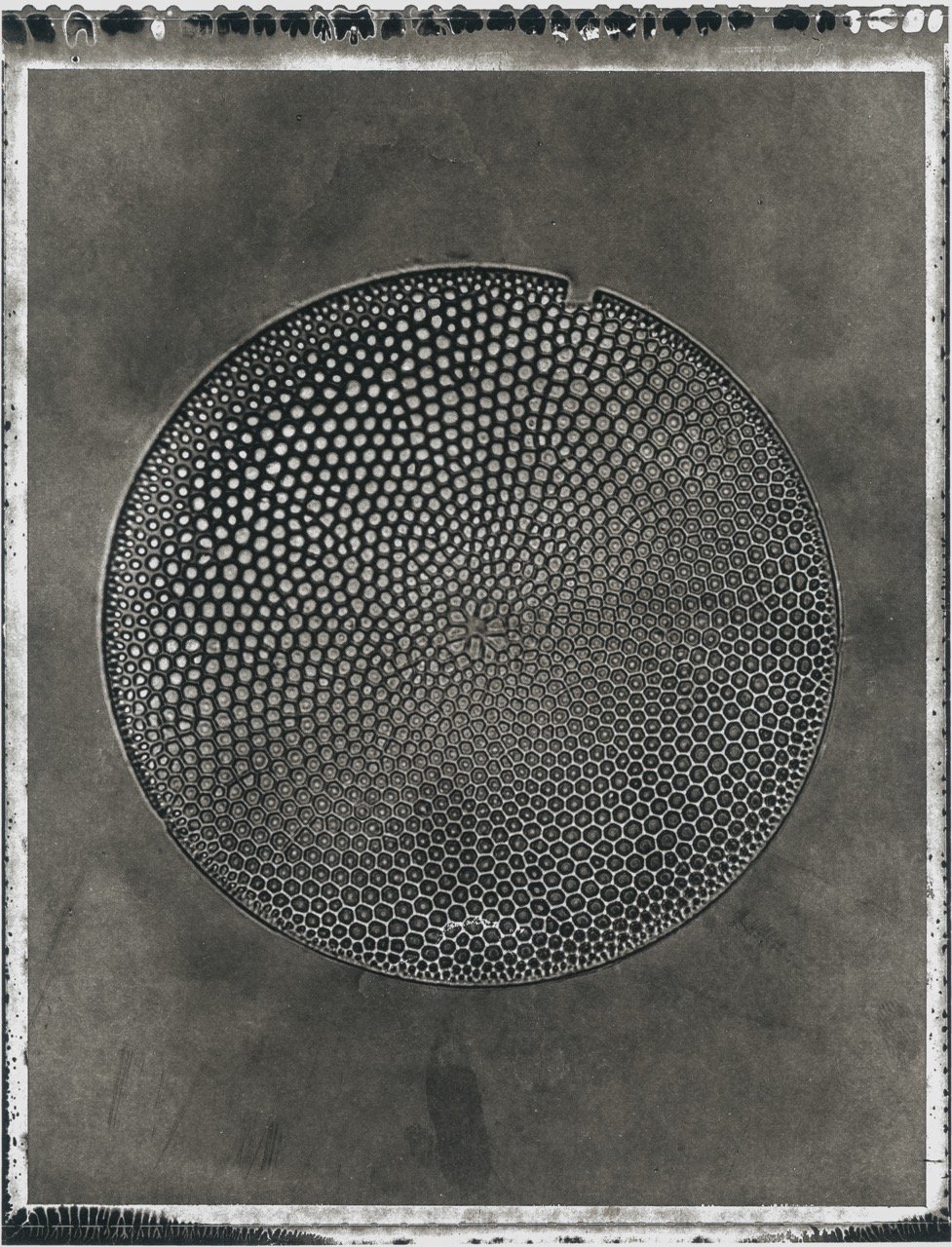

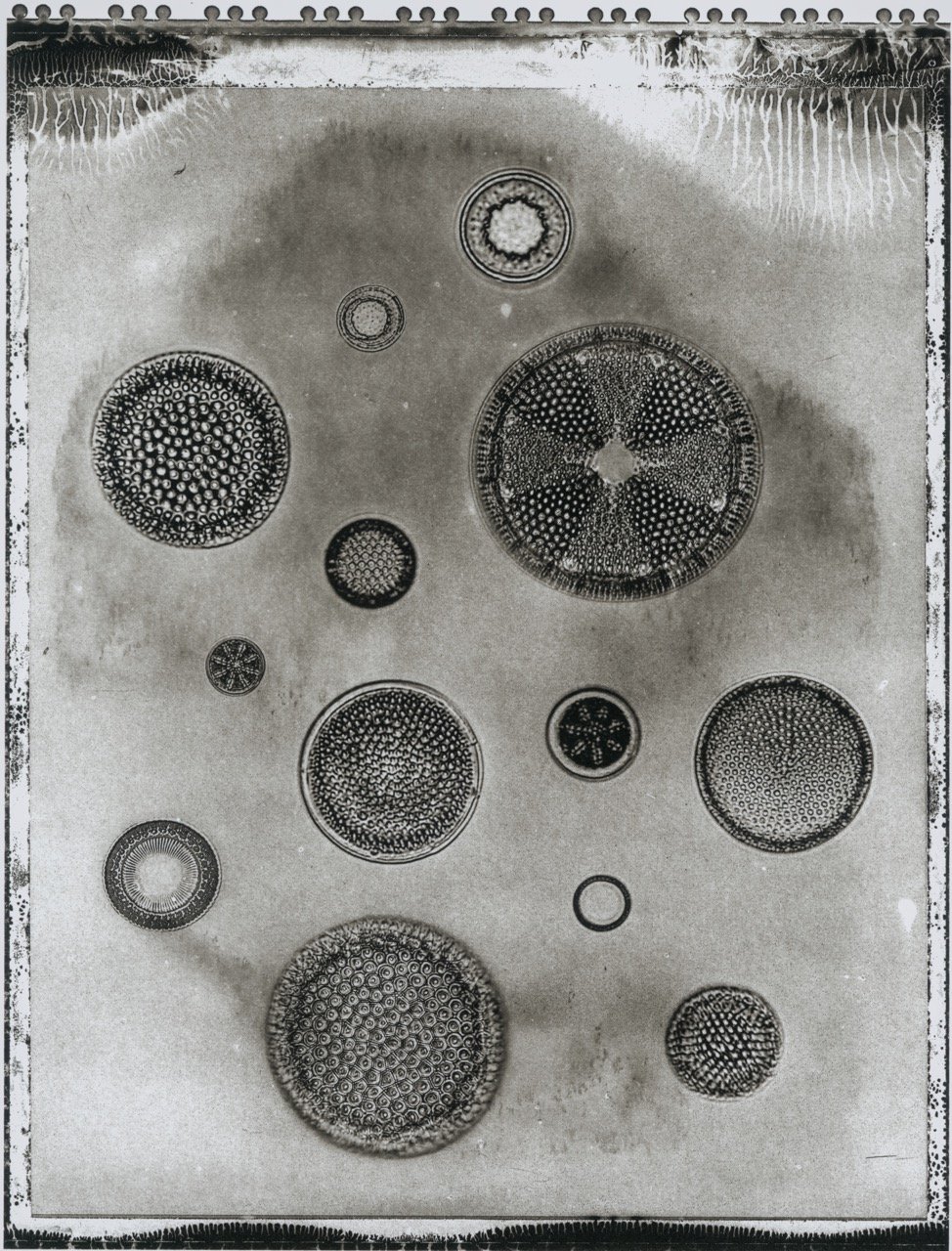

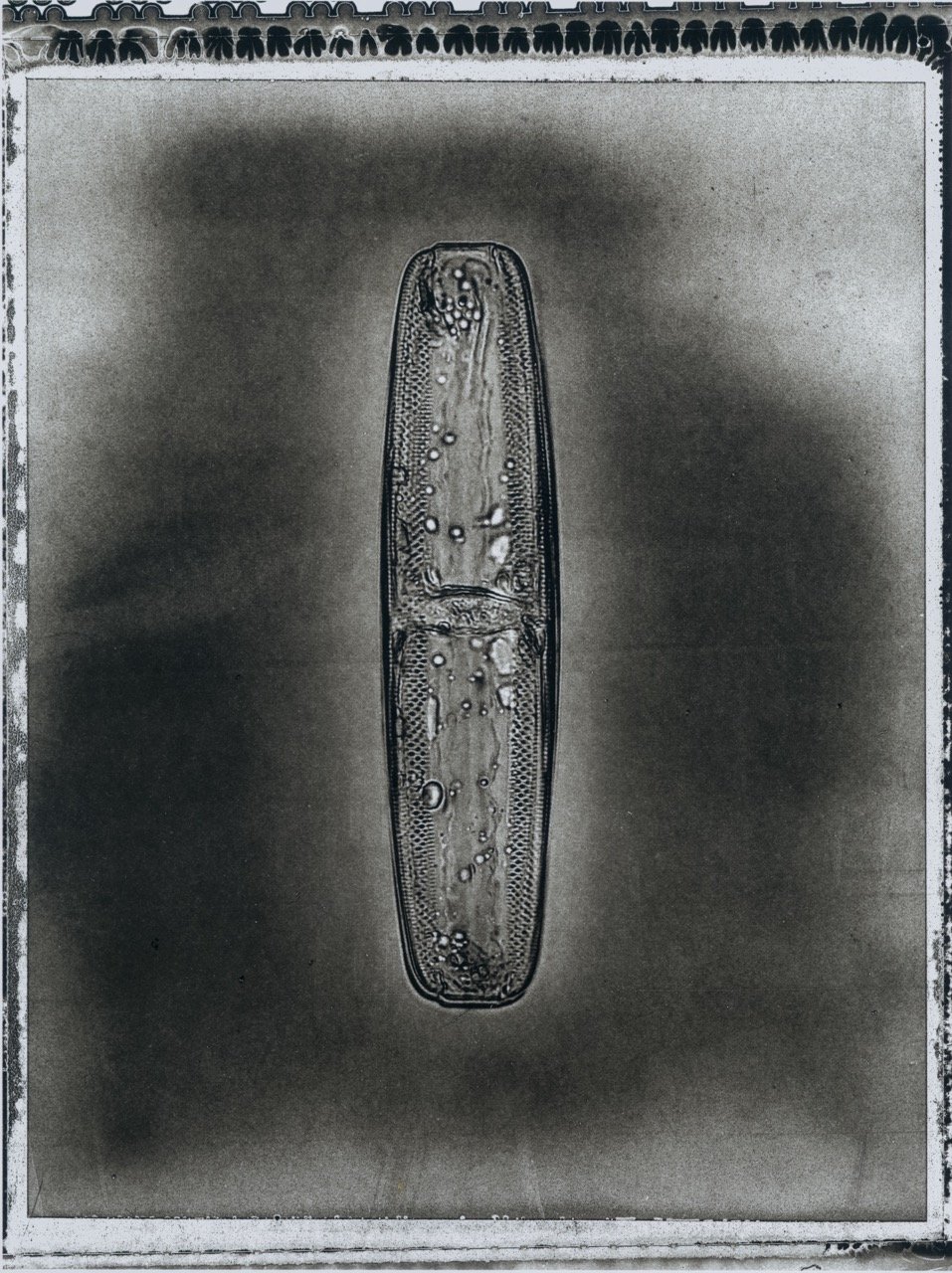

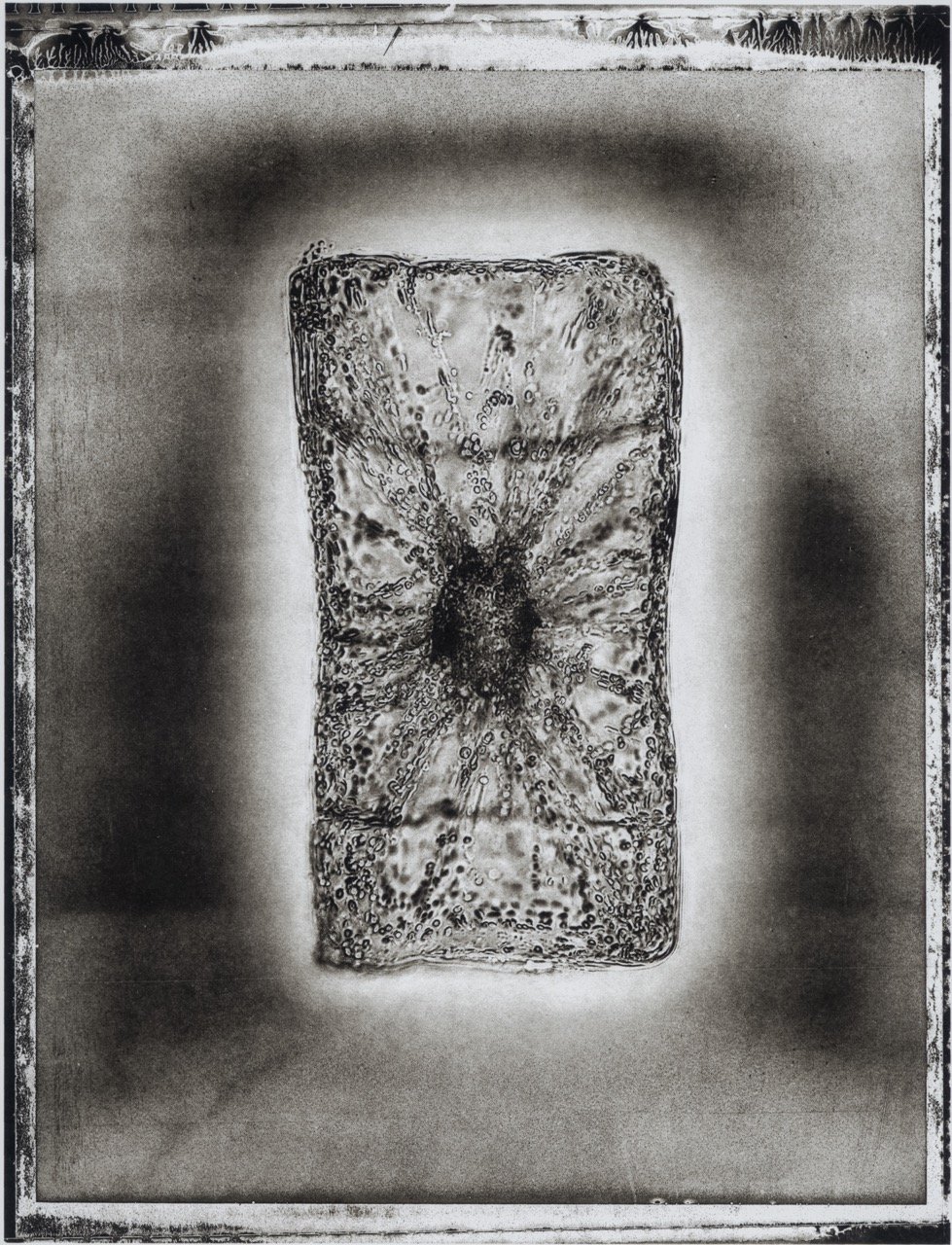

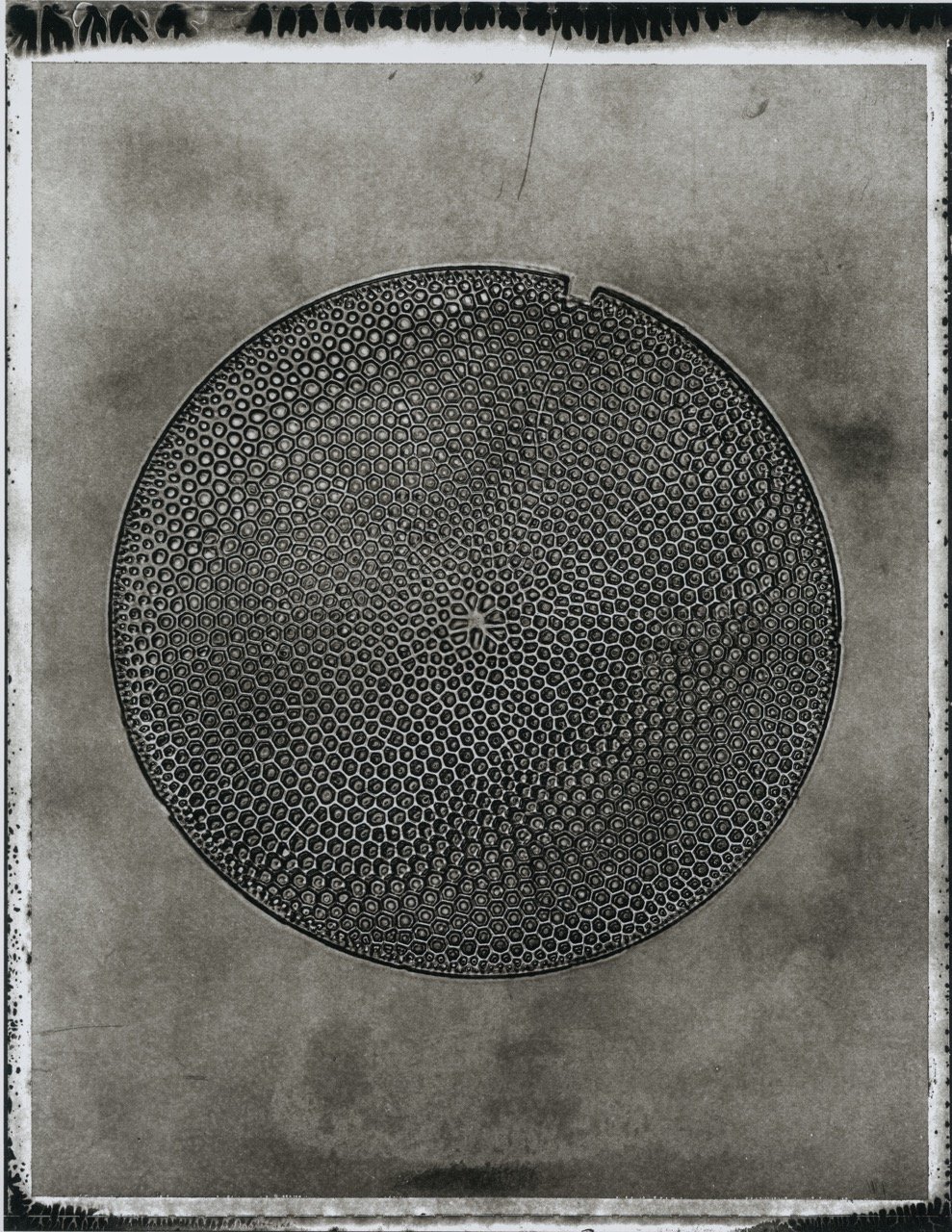

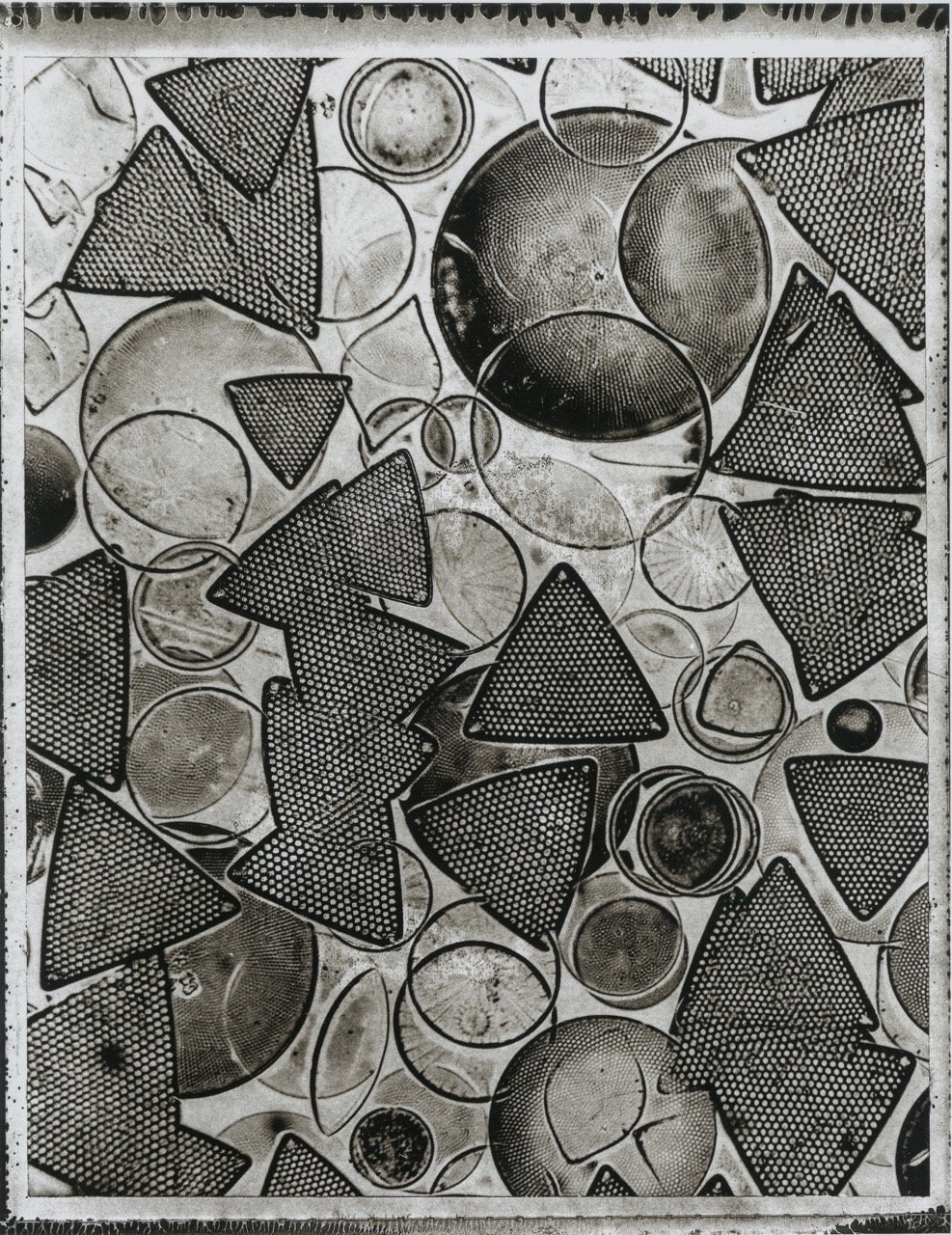

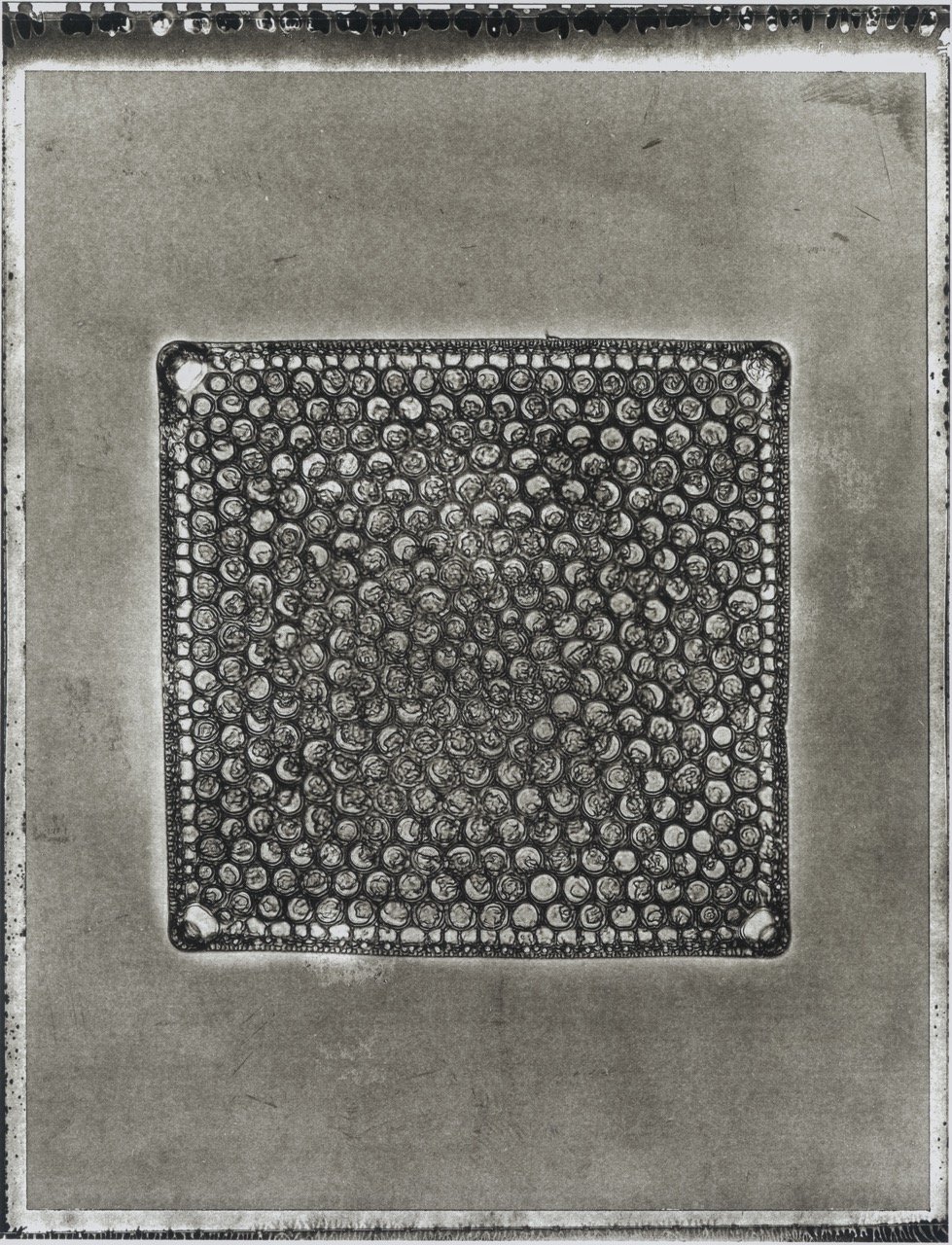

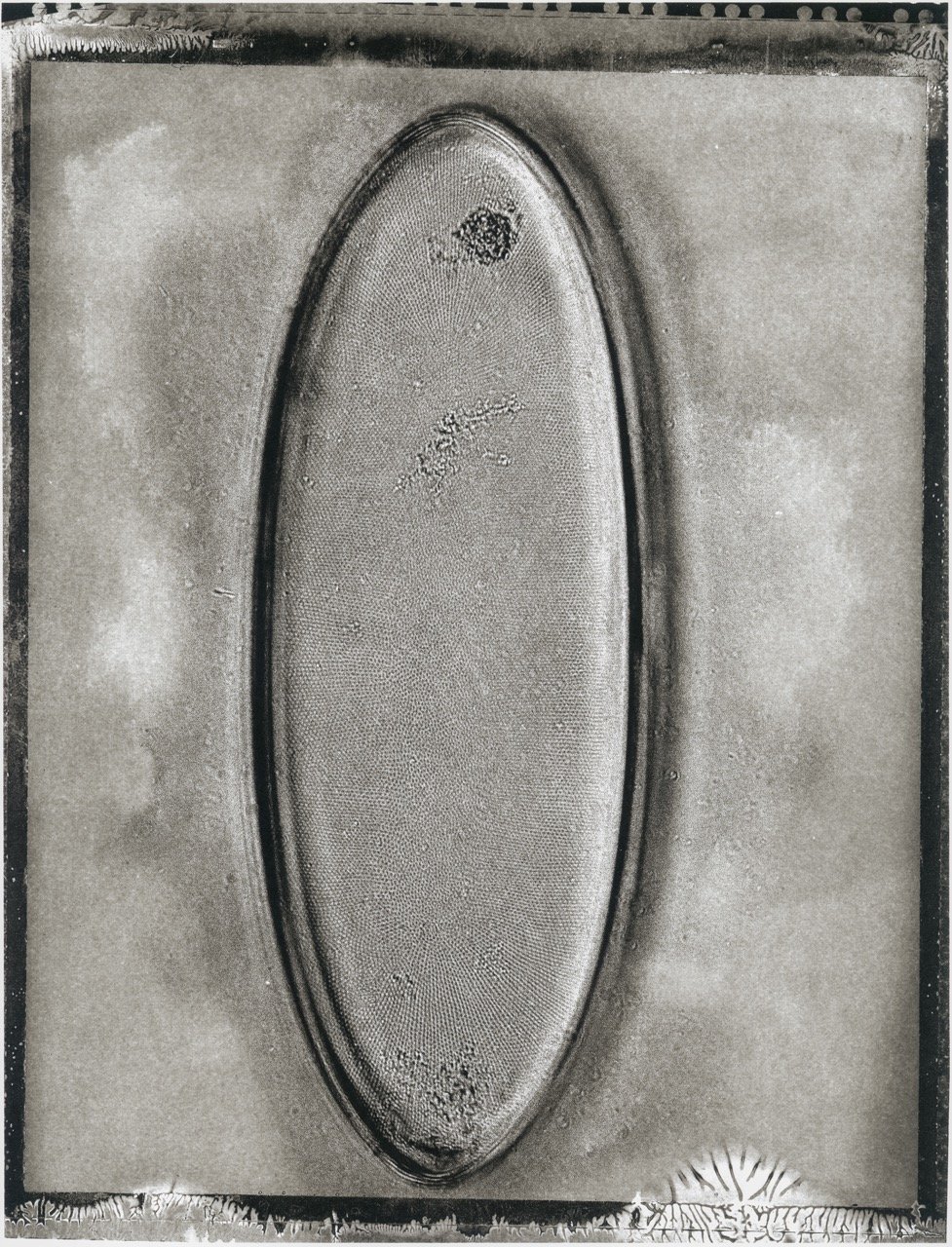

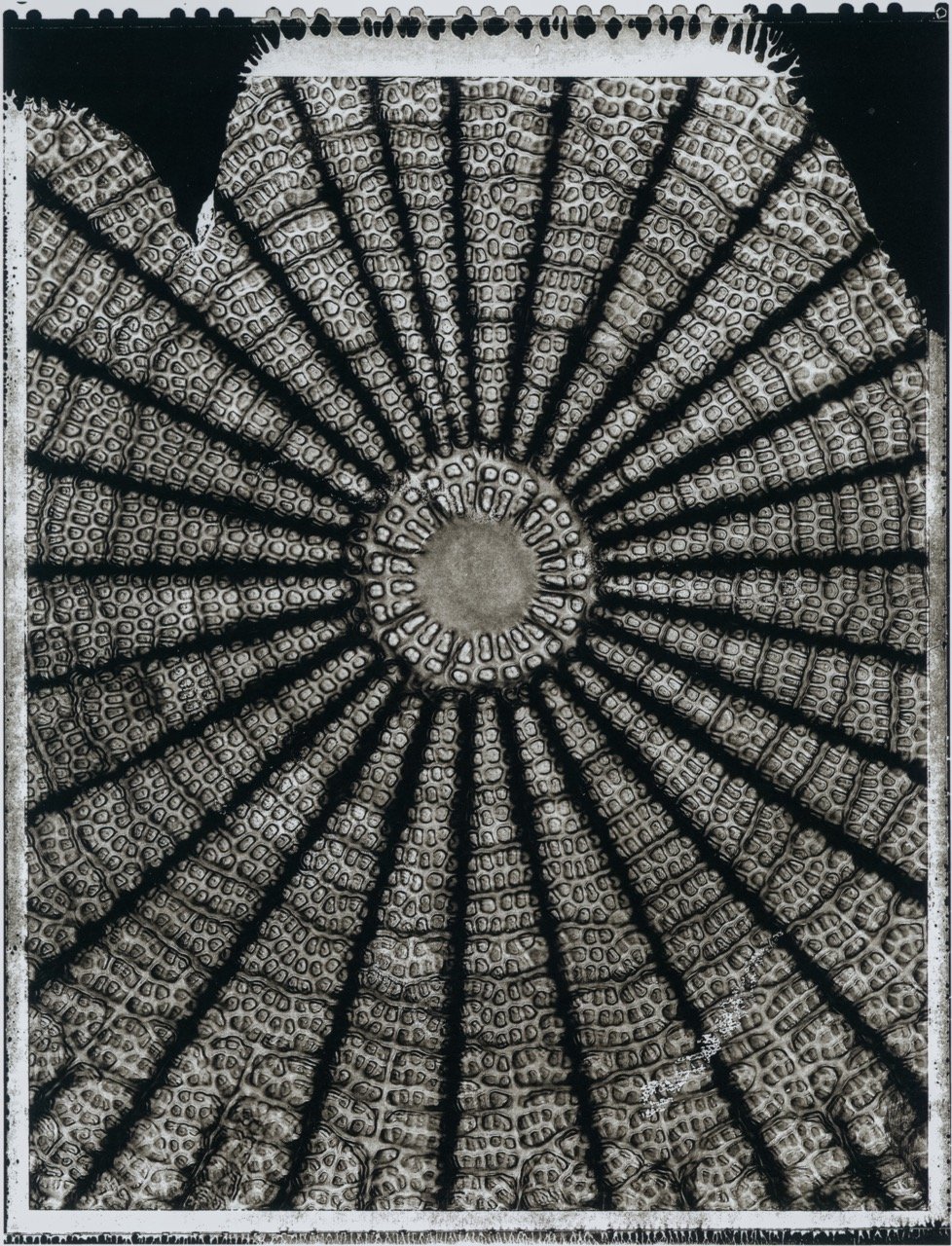

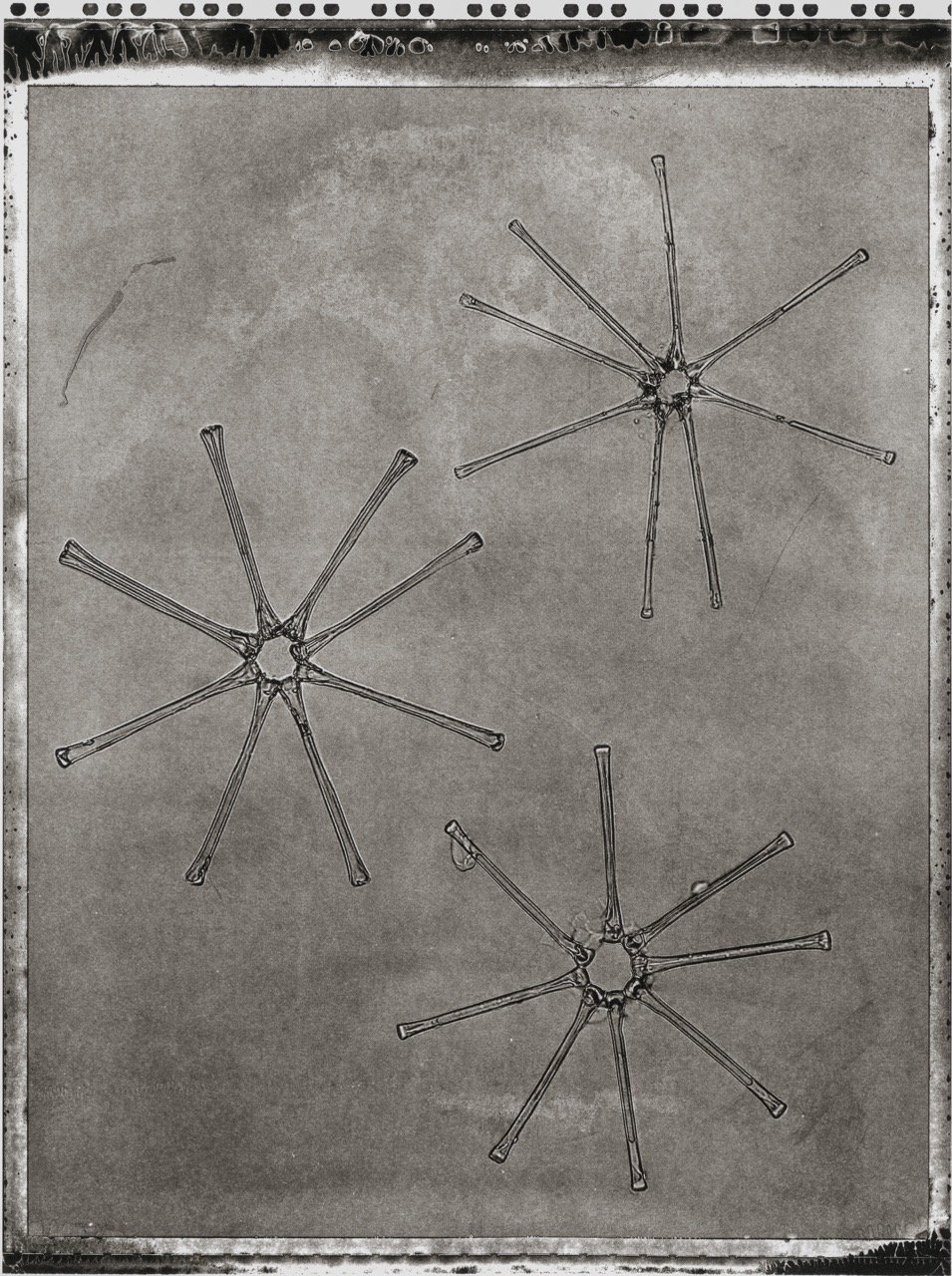

Diatoms are single-celled algae, silicon-containing and photosynthetic, that float in the oceans and freshwaters. These species generate their food through photosynthesis; hence, they are the founders of the food pyramid. Phytoplankton are classified into three major categories, and they are known to be the wealthiest formations on our planet Earth. There are approximately 4-5 octillion, a number written with 27 zeroes, phytoplankton in our oceans and seas, but until 35 years ago, people did not even know they existed.

Let us travel back in time to a period four billion years ago; there was no life on Earth, and there was no oxygen on Earth. Around 2.5 to 3 billion years ago, the early relatives of some of today's phytoplankton emerged and started harnessing the sun's energy and converting water into its constituent elements: oxygen and hydrogen. They used the chemical energy produced to fix carbon dioxide (CO2) to construct sugars, proteins, and amino acids—all organisms on Earth are made of. It also took millions of years of evolution to produce enough oxygen to build up in the atmosphere. For significant types of organisms to develop in the Earth's environment, there was a need for oxygen, and this came around half a billion years ago, leading to the production of significant forms of life and the development of human beings.

These photosynthesizers died. They sank to the deeper parts of the sea and sat there for millions of years to form fossil fuels. Today, these ancient organisms' descendants continue to feed the living things on Earth in one way or another. In other words, your heart pulsates with the help of solar energy, which is transformed by beings such as phytoplankton. The components in our bodies are mainly made of carbon, which is metabolized by these minuscule organisms. These organisms quietly drive the world we inhabit.

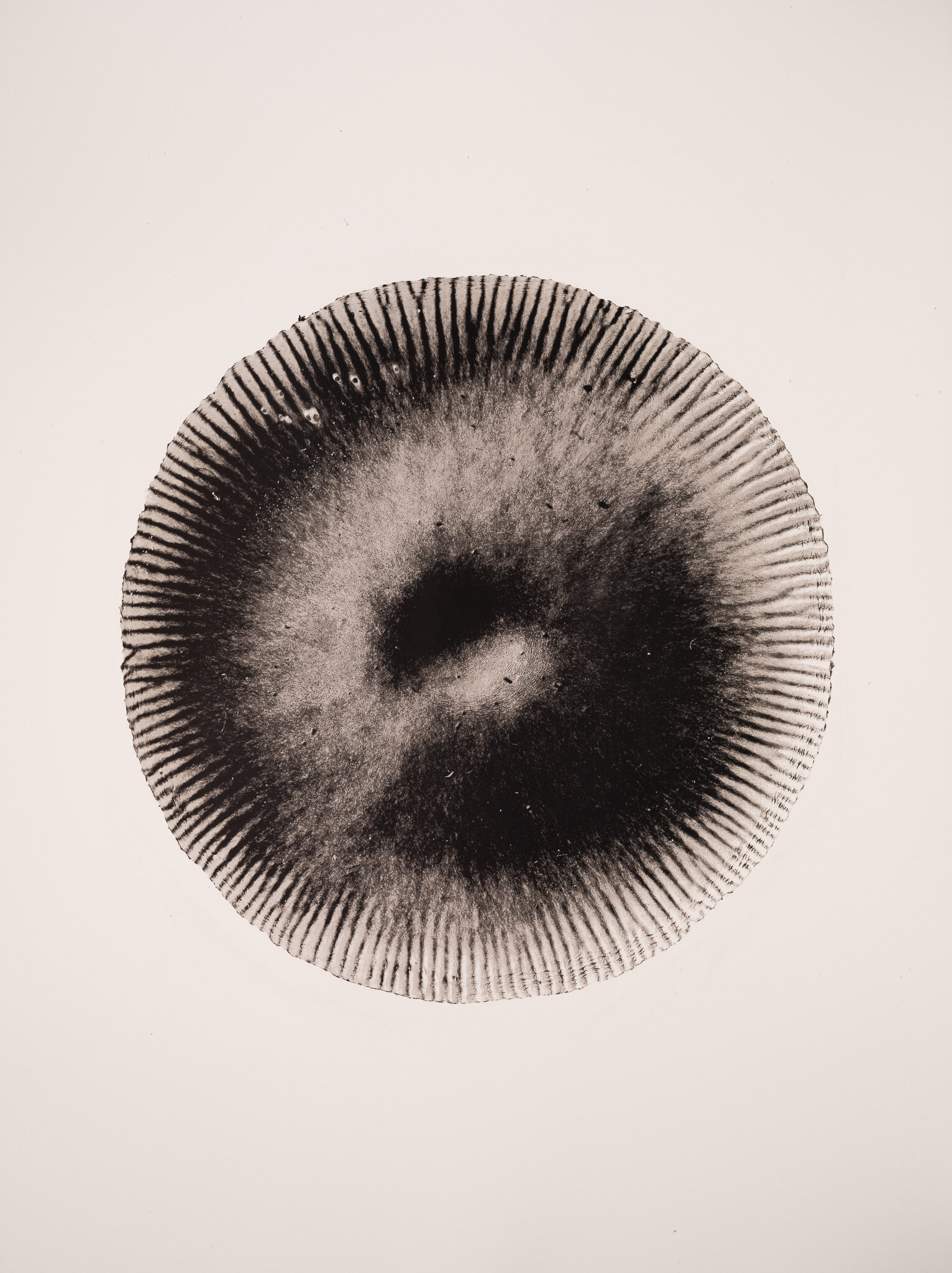

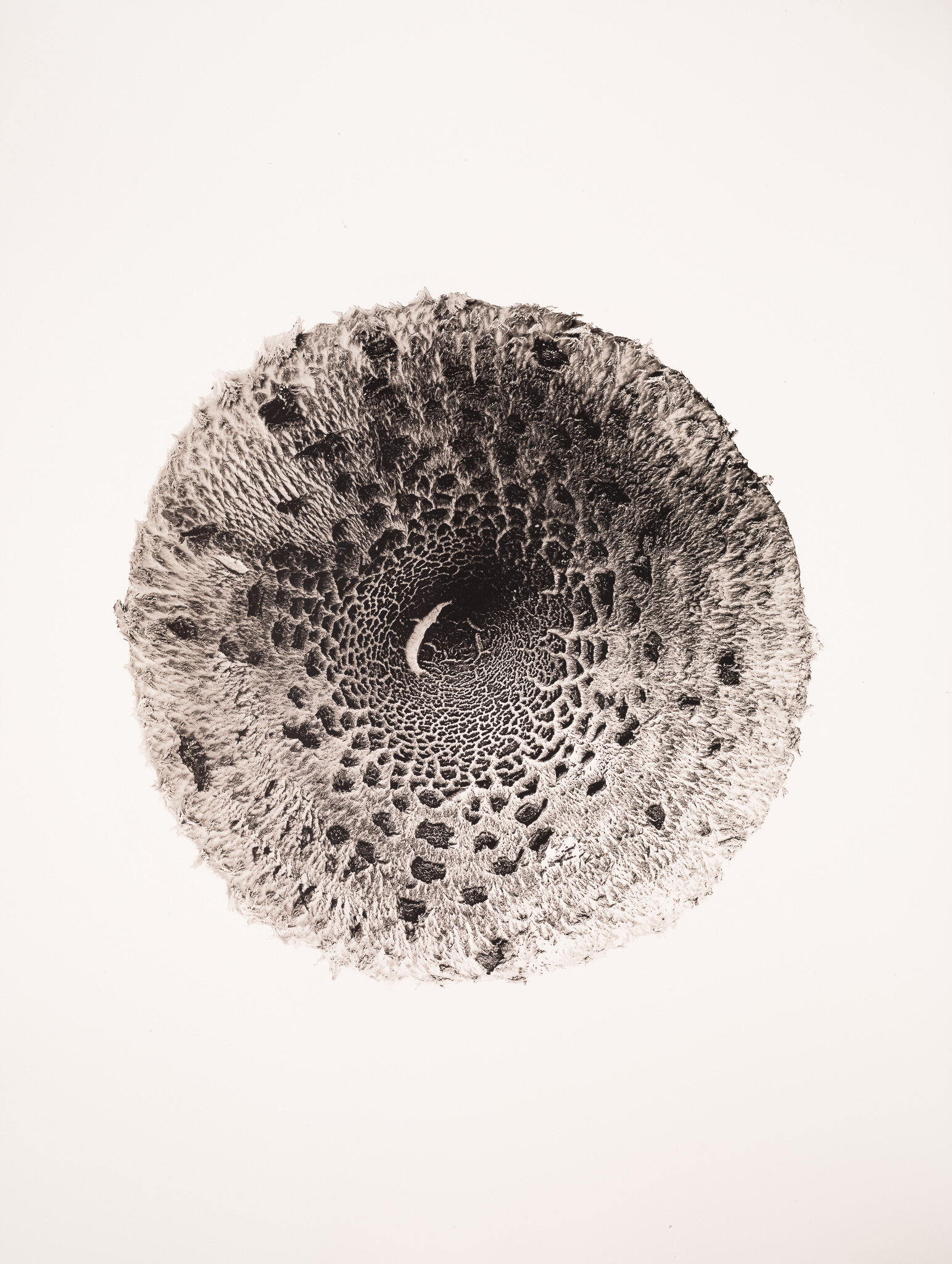

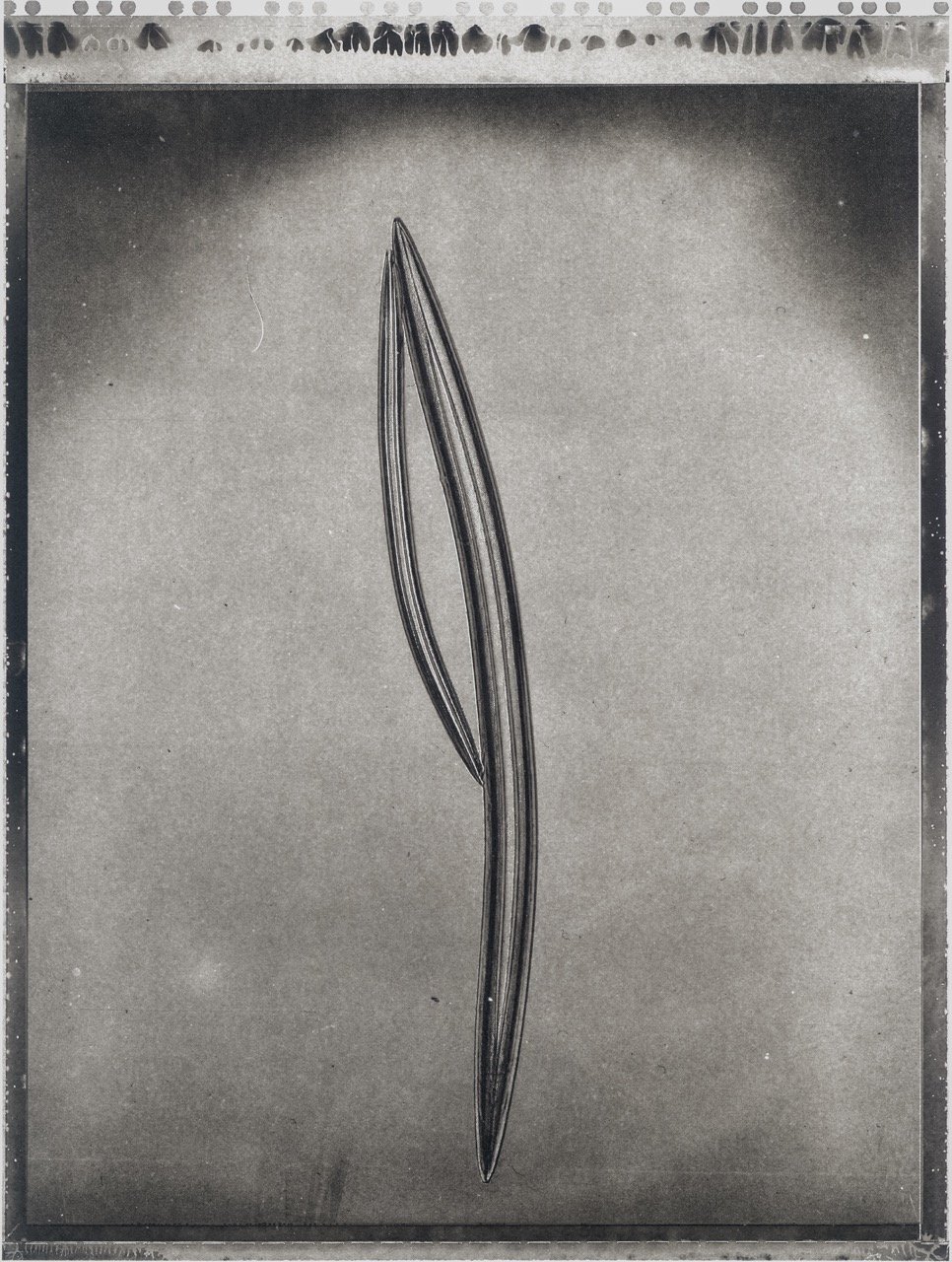

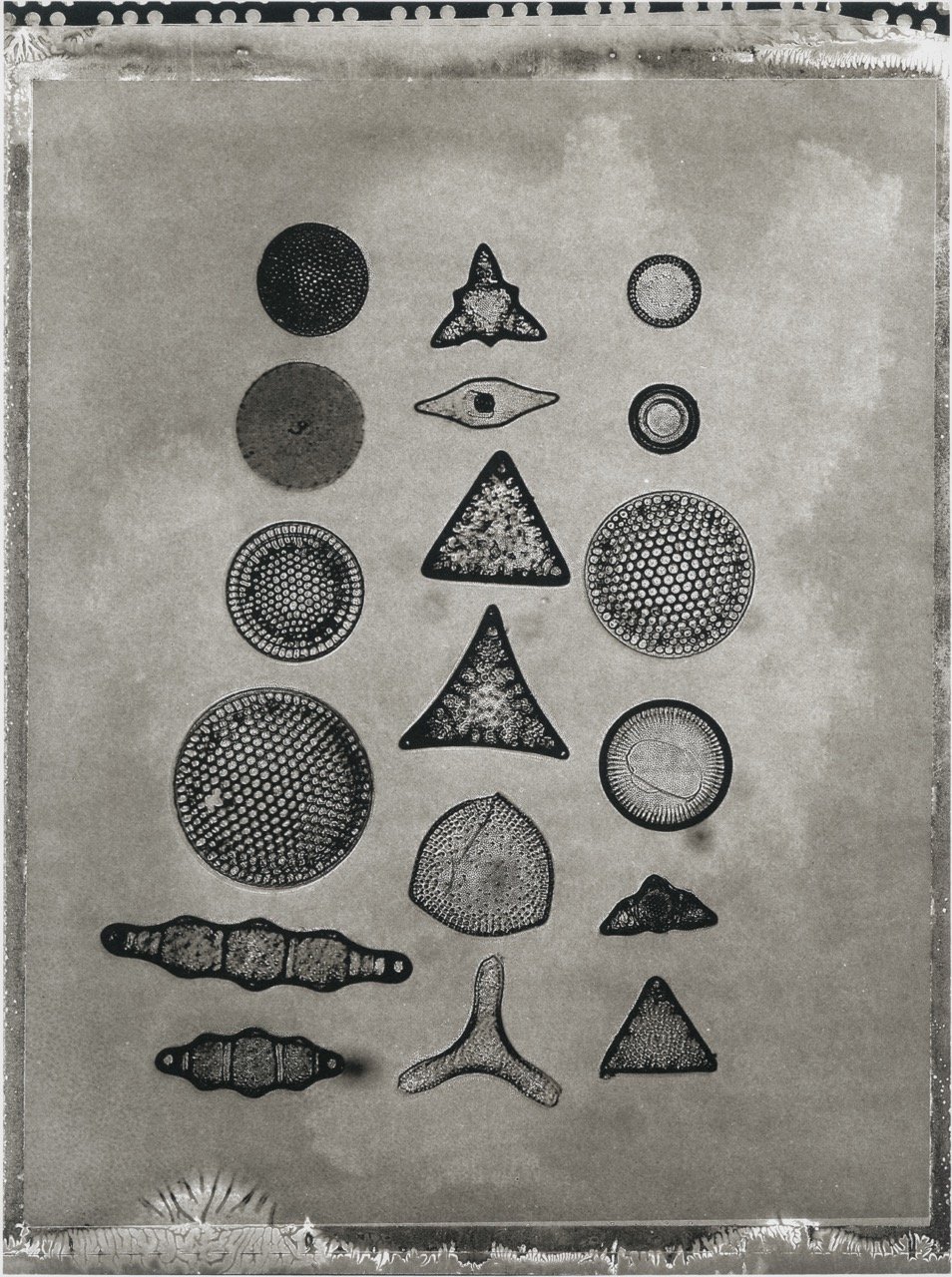

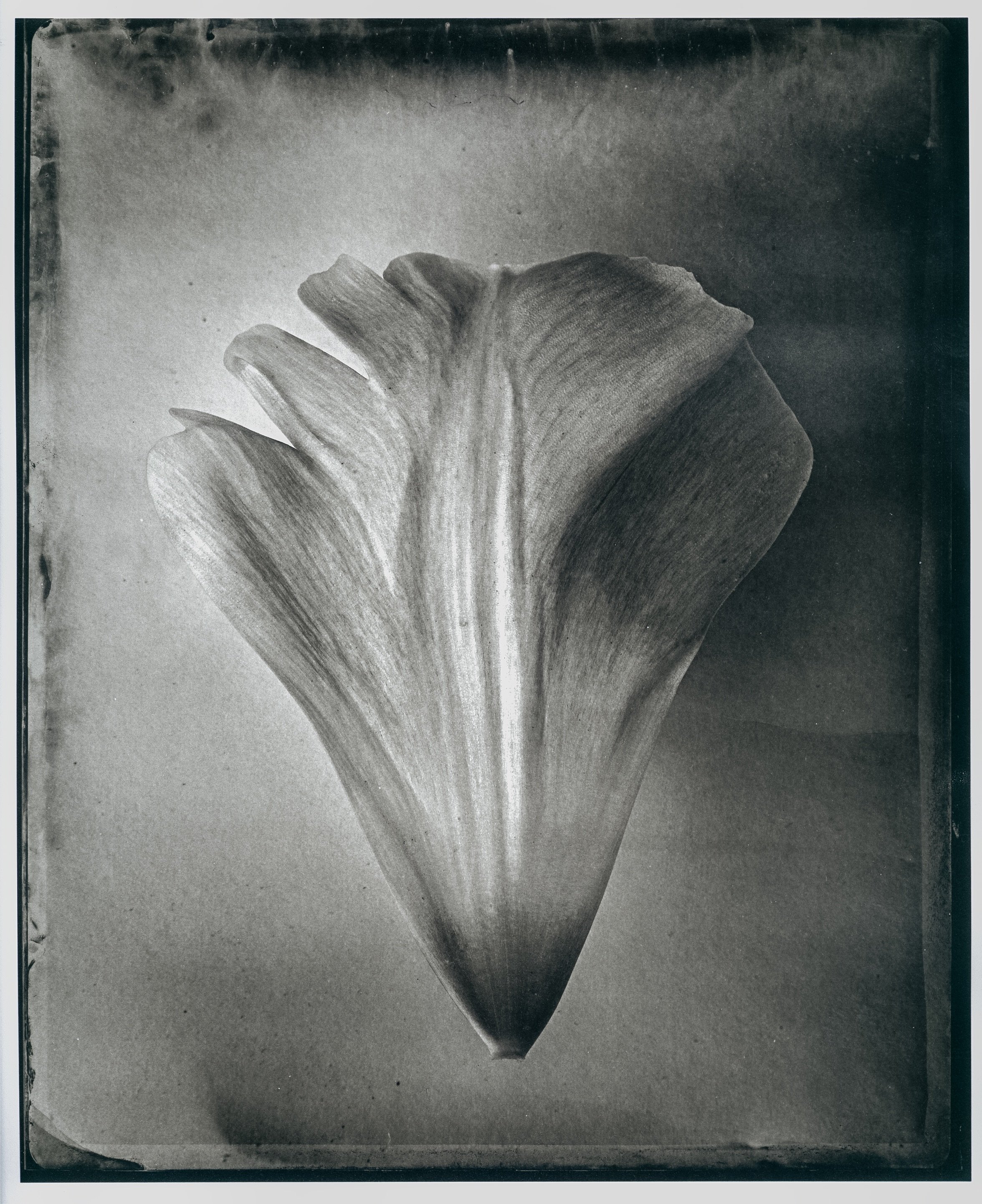

Phytoplankton are classified in the plant kingdom, and there are thousands of different species ranging in size and shape. On average, phytoplankton are about as big as a tenth of the human hair diameter and can only be seen with a microscope.

There are three main groups of phytoplankton:

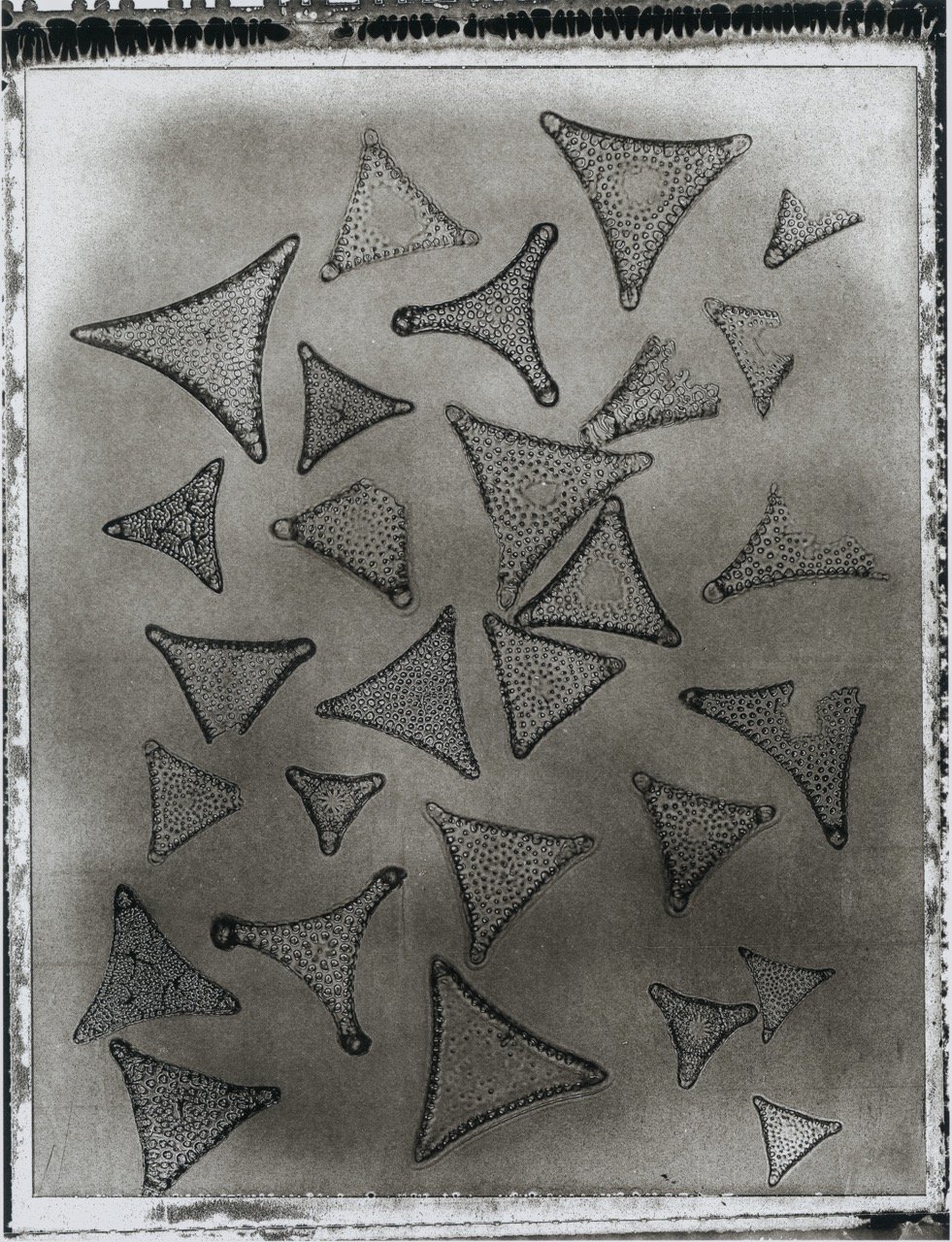

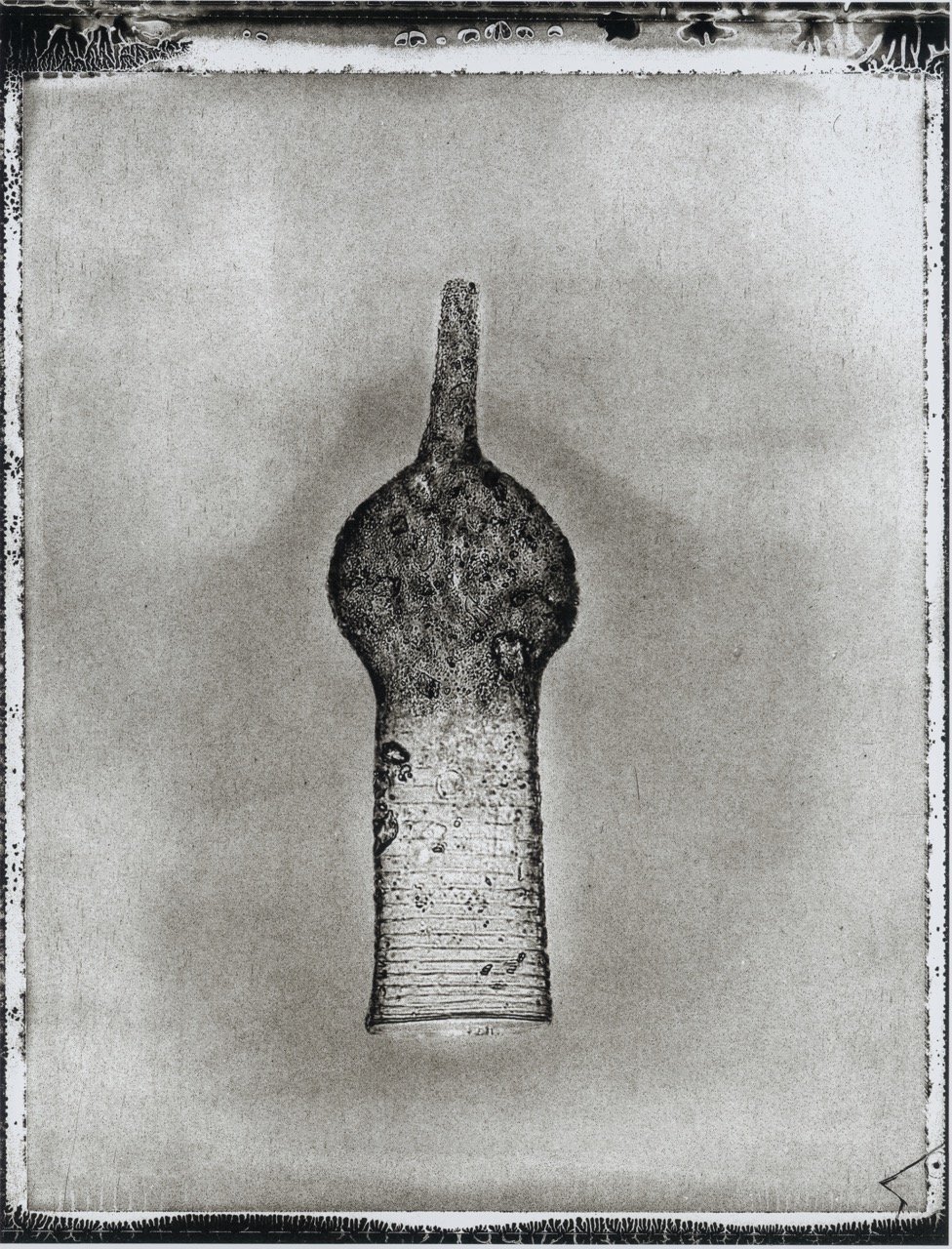

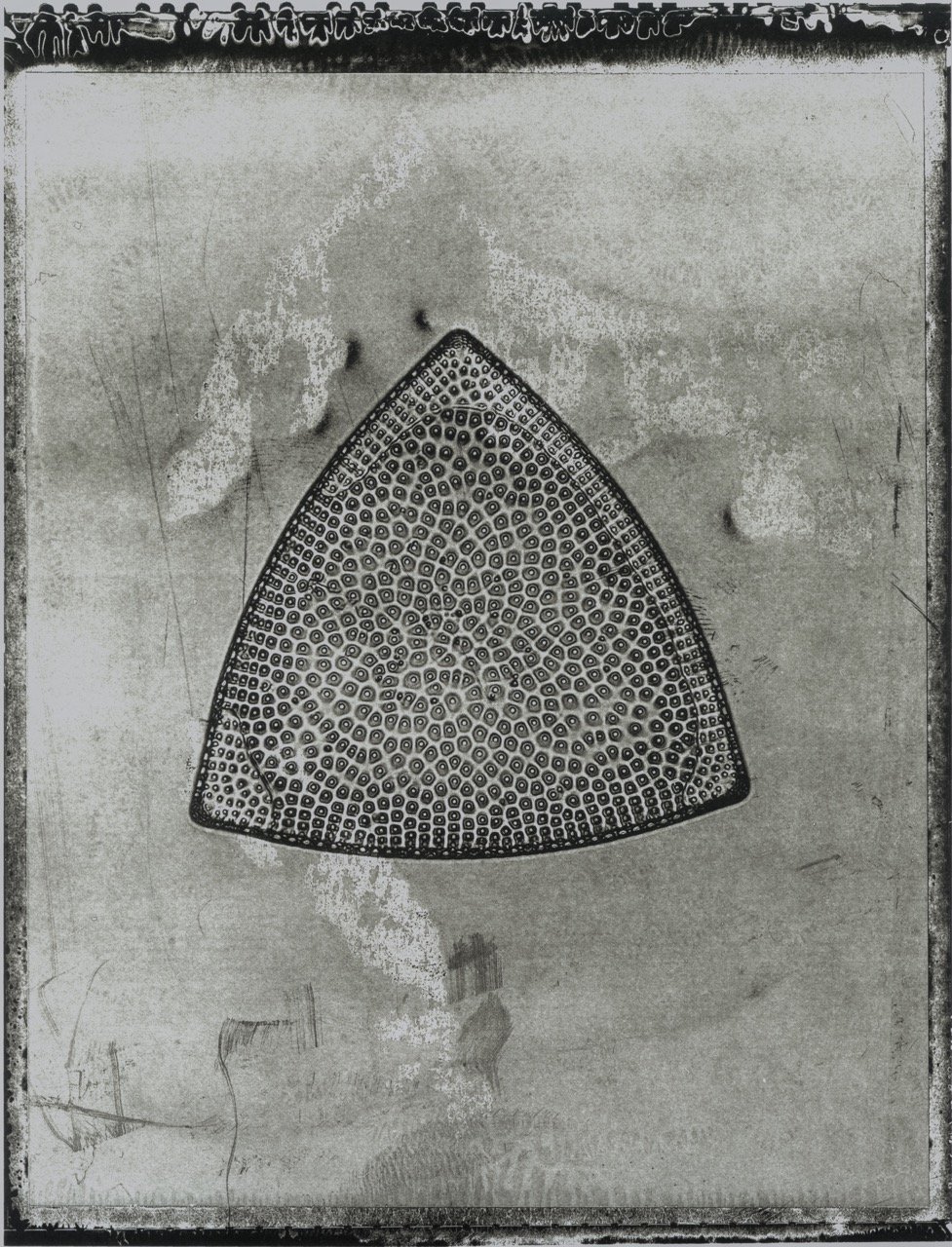

Diatoms: Diatoms have cell walls made of a material similar to glass, primarily silica. These complex structures, labeled as frustules, provide protection and structural support. The organism is ordered at the microscopic level that it is produced artificially with some high-tech program; each diatom is different. Diatoms are the most prominent form of phytoplankton and cite a significant degree of interactive carbon within the photosynthetic process.

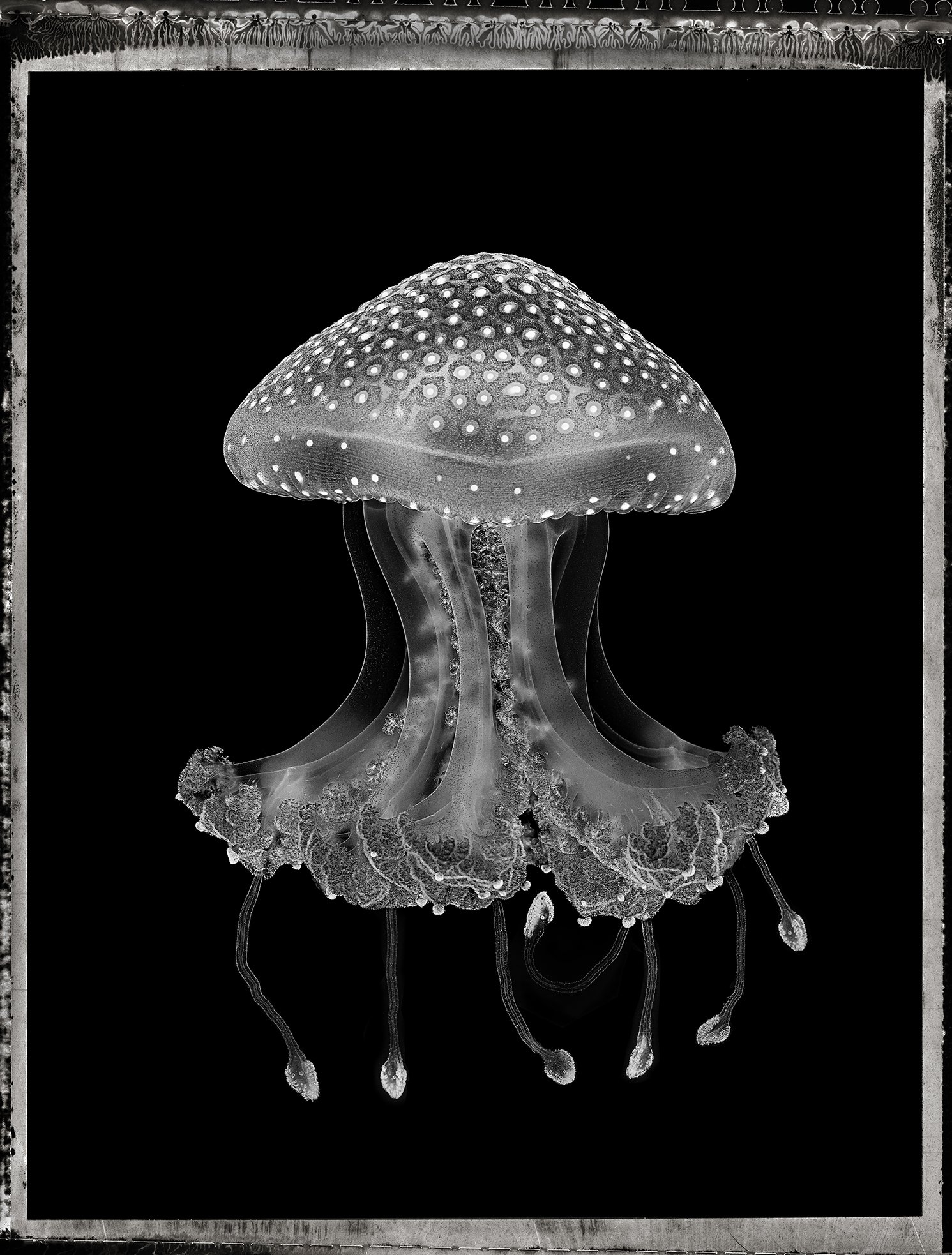

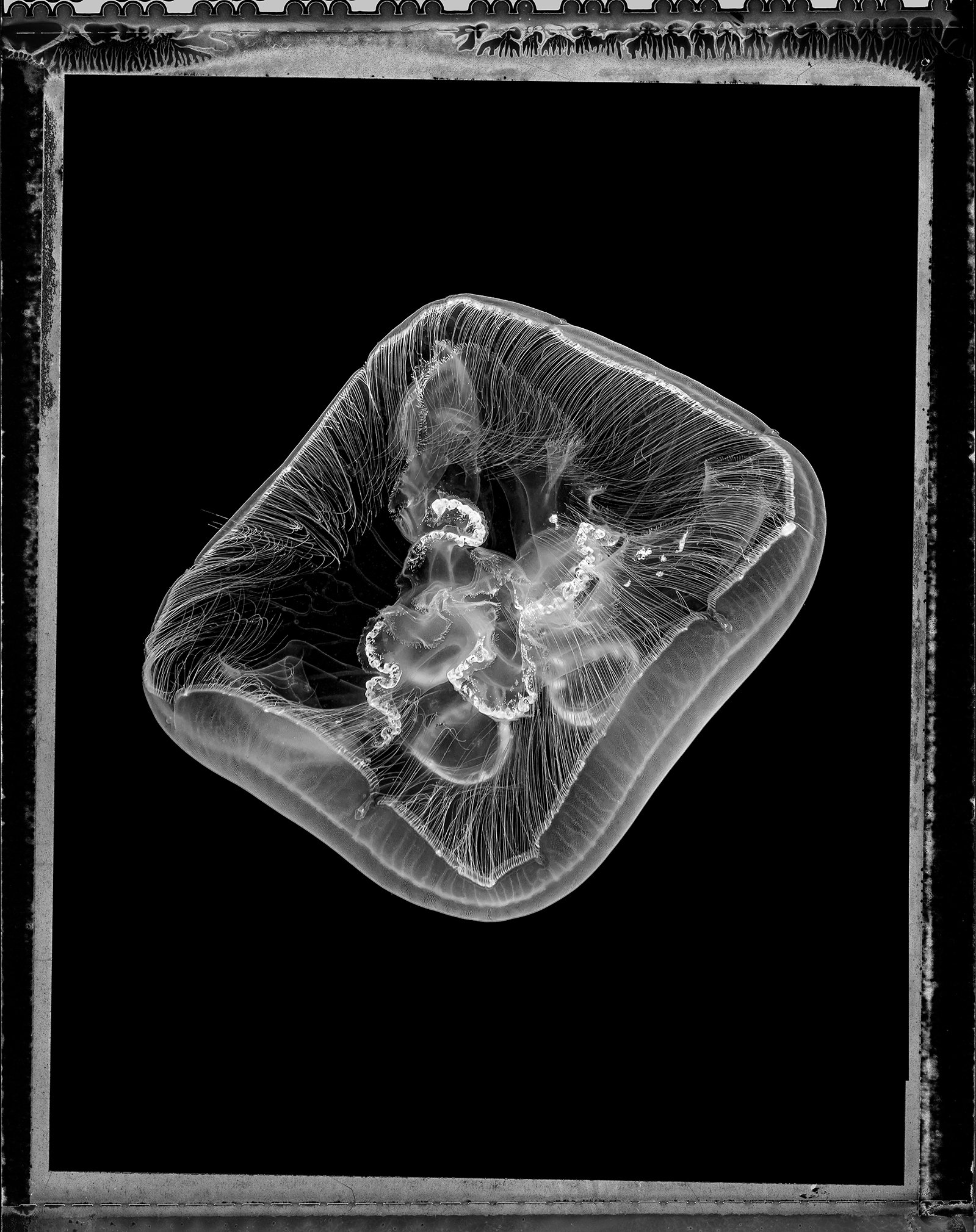

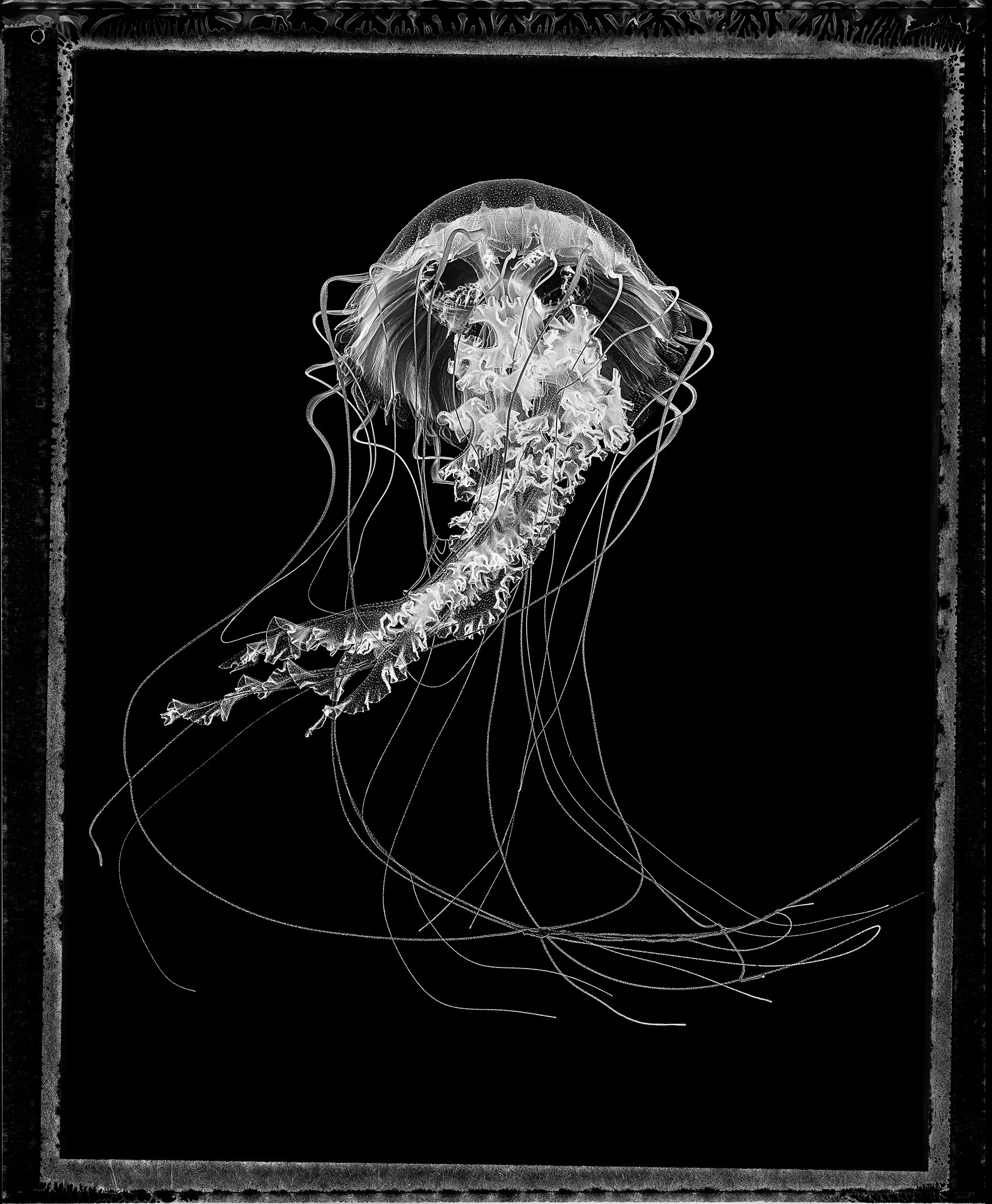

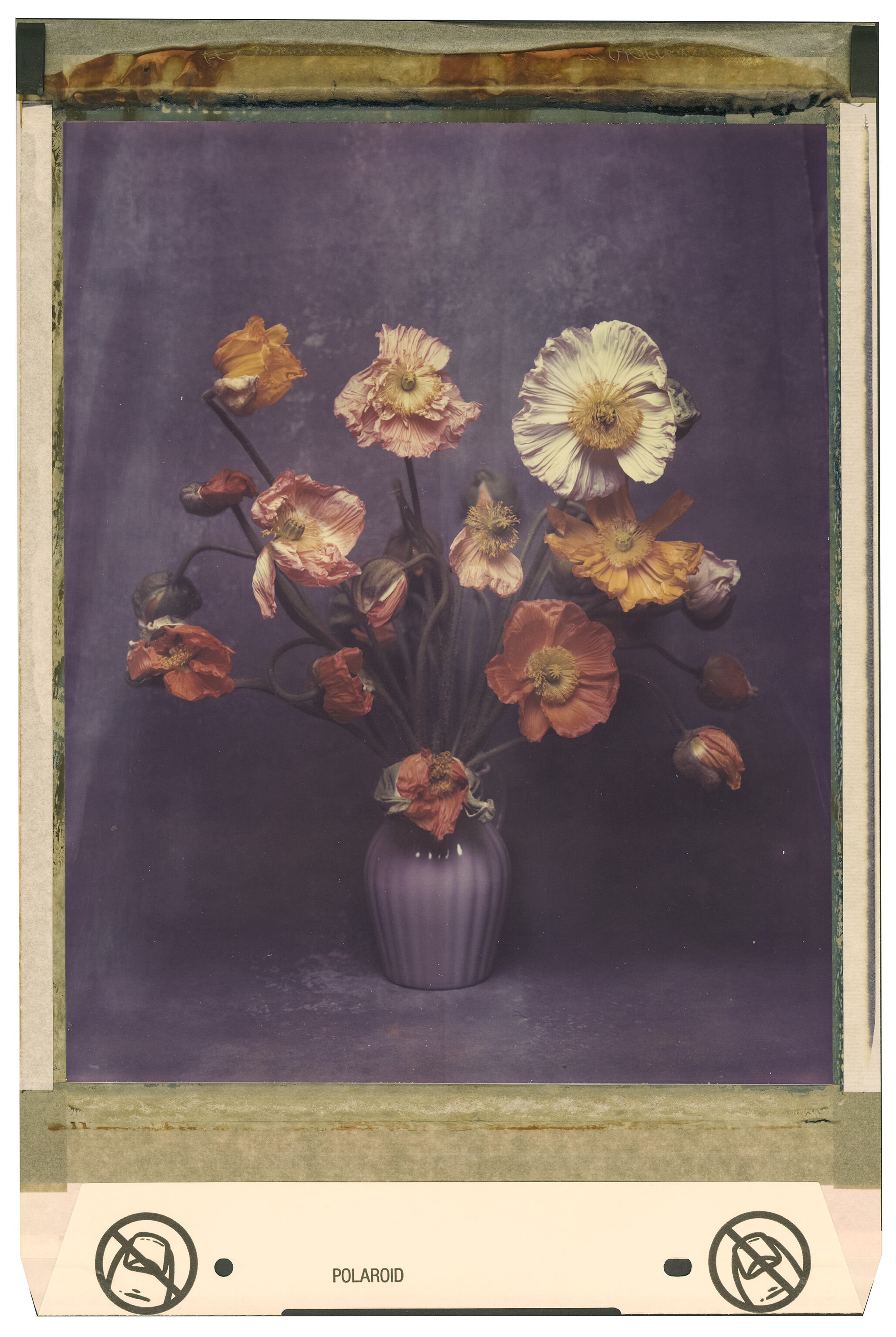

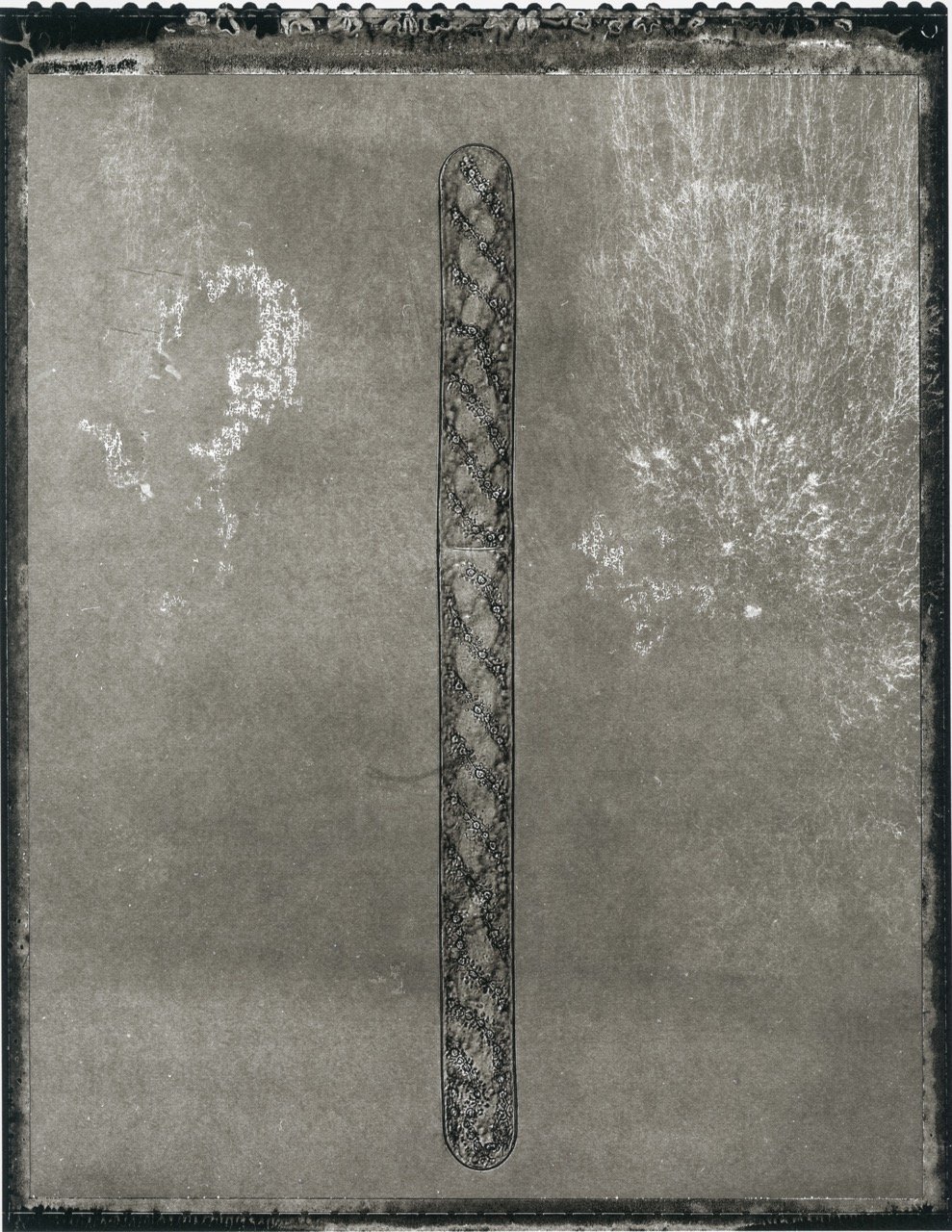

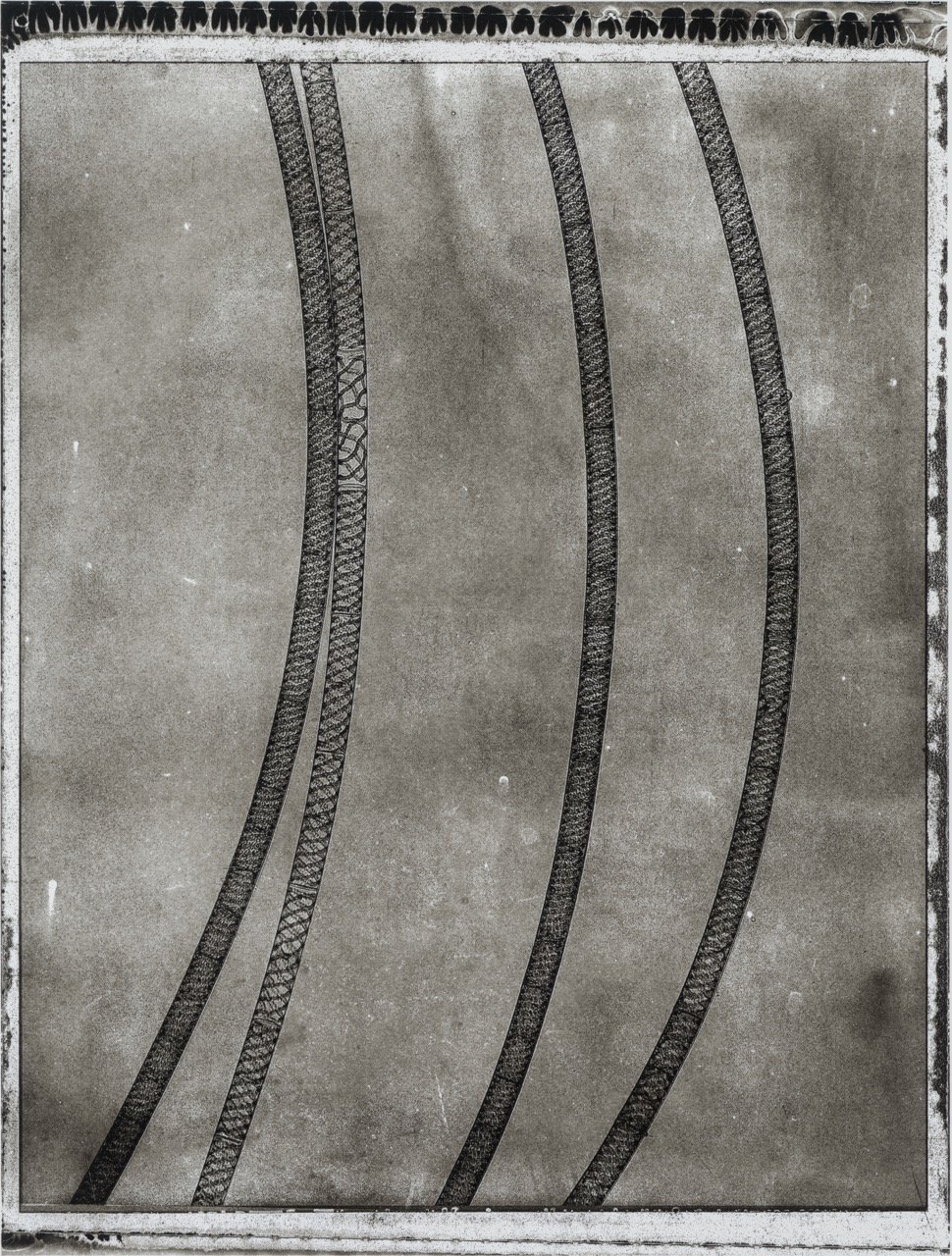

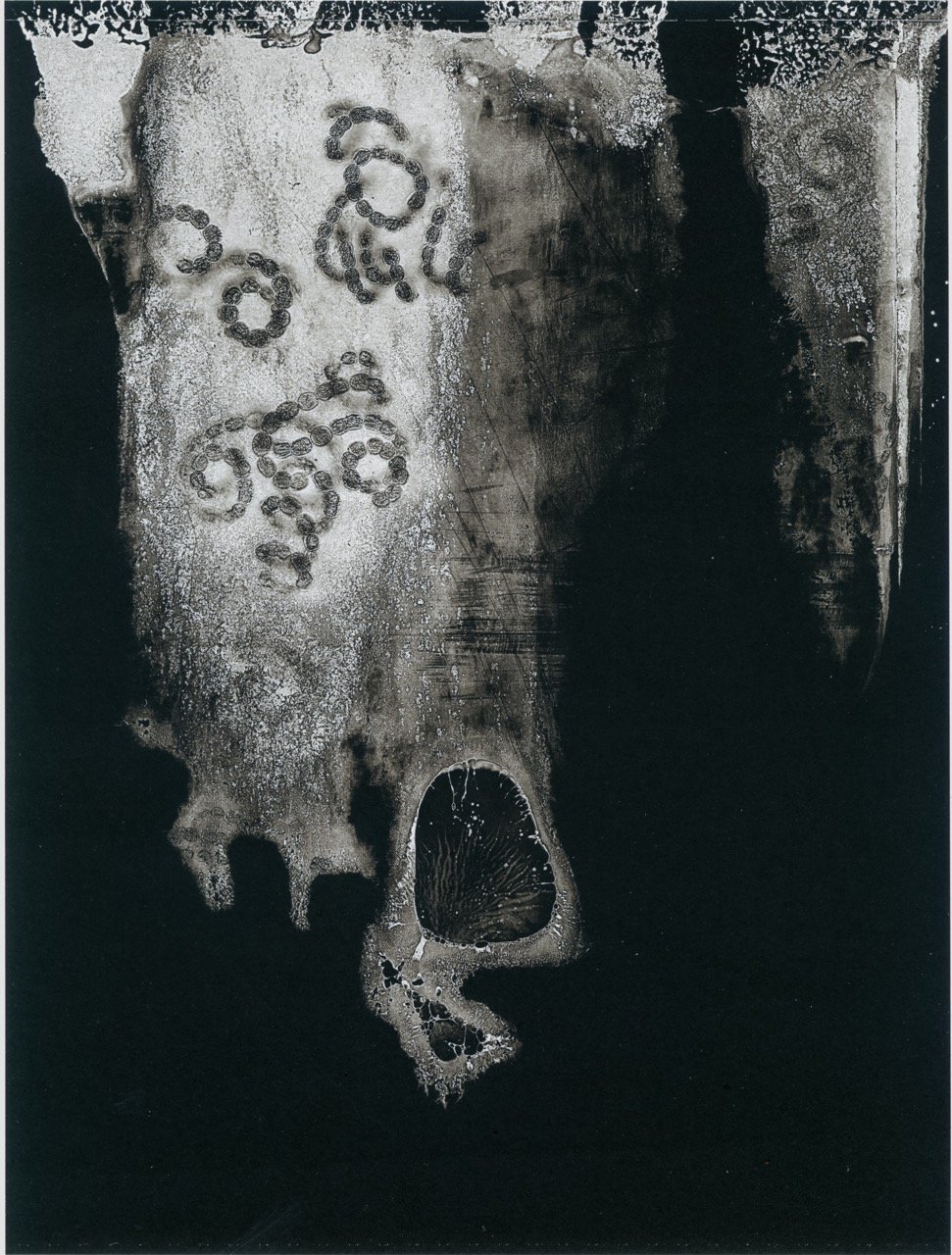

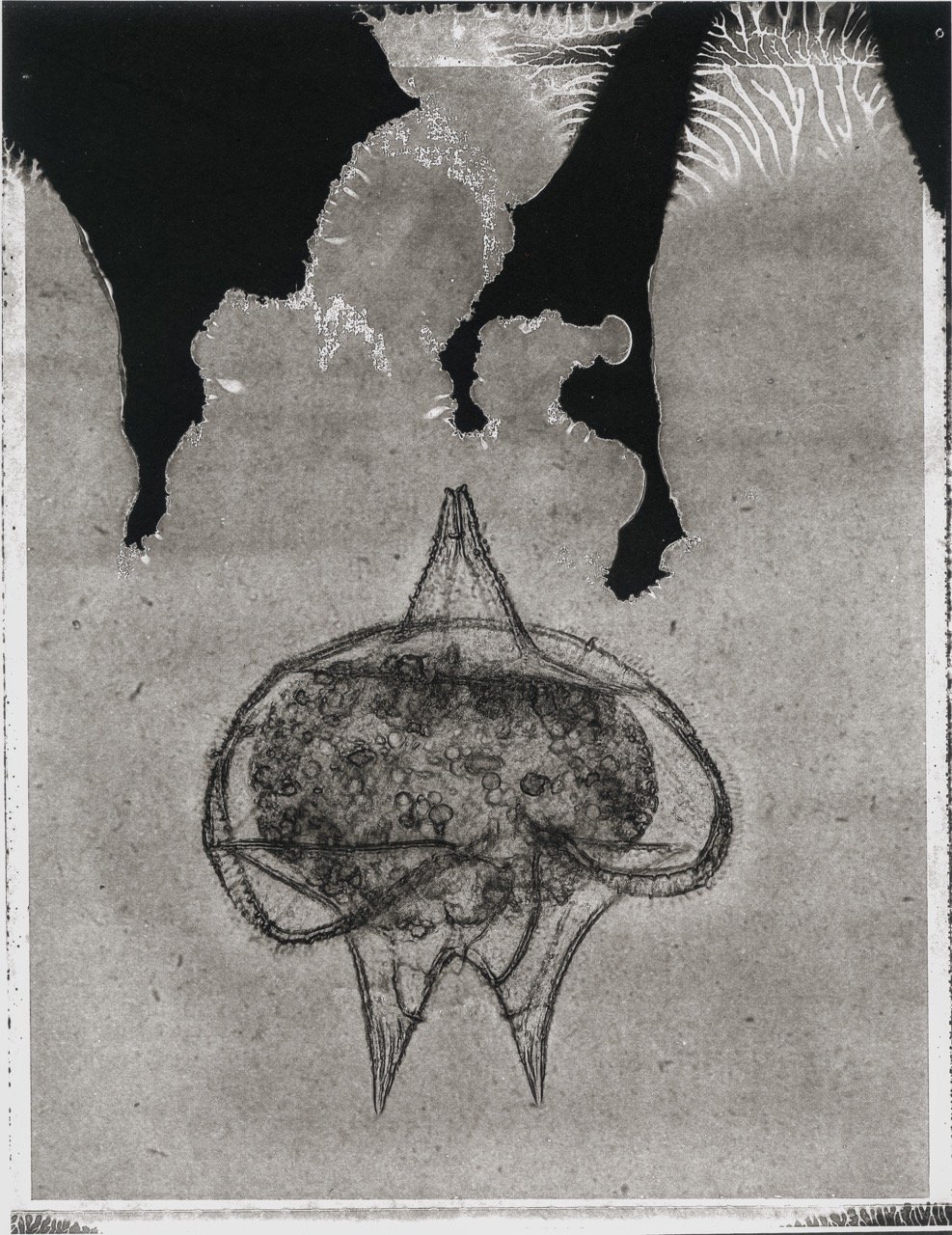

Dinoflagellates: Dinoflagellates are also smaller compared to diatoms and are characterized by two flagella for their mode of transportation. It is also observed that most species can produce bioluminescence, hence making water glow.

Cyanobacteria: Phytoplankton comprises many small organisms; the smallest of these organisms are the cyanobacteria, the largest group of organisms on this planet. They play a special role in the nitrogen-fixing process and use light energy to synthesize glucose and oxygen. The oxygen-generated cyanobacteria were discovered only in 1985 and provide 20% of the oxygen required by human beings. Regrettably, these microplastics are lethal to these bacteria.

Thus, I'd like to shed some light on the existence and functions of phytoplankton so that people can also appreciate this form of life.

The Development of the Marine Food Chain

Phytoplankton are mostly found at depths of up to 200 meters in the sea and are the foundation of the whole marine community.

Some animals live among them and eat them, while others flock to the water's surface to feed on them during the night, and others lie in ambush deep in the waters to feed on these when they die and sink. For example, copepods and other marine animals that are part of the zooplankton move from the deeper parts of the water mass to the surface to feed on phytoplankton, after which they are expected to return to the deeper water in the morning. It remains the most significant movement of mass animals on the Earth's surface and transports water more than the moon and tides. The energy transferred through this migration is massive and was only realized recently.

Organisms belonging to this category are crucial in the marine food chain because they are the primary producers. Phytoplankton are consumed by zooplankton, which in turn transform the energy into biomass, which are consumed by small fish and other invertebrates. These, in turn, feed on other smaller fish and marine life, such as sharks, whales, and other large fish. This web of food relationships demonstrates the importance of phytoplankton as the base of the marine food pyramid.

I have at home a water tank for jellyfish, and I also breed zooplankton (Artemia) to feed the jellyfish, which inhabit another aquarium. I also cultivate phytoplankton in another jar to feed my zooplankton.

A decrease in the levels of phytoplankton in the seas would affect the overall health of sea-relying organisms and ecosystems.

Every Other Breath

Though microscopic, these species of plants and algae combine to be lighter than about 0.01% of the total mass of the planet's land plants, like the Amazon rainforest, yet they account for more than half of the oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere. These oceans are where these marine plants are found, which are considered the lungs of the Earth. In technical reports, about 50% to 80% of the world's oxygen is expected to be generated in oceans. This figure may be slightly higher, averaging 90%, based on a GOES study.

Annually, phytoplankton convert and sequester 40 to 50 billion tons of carbon dioxide into their bodies, enriching the oceanic bounty. The carbon released into the atmosphere must be retrieved — or, as it is referred to, the carbon cycle. They lock in carbon or transform it into oxygen and other products through photosynthesis. They are phytoplankton whose abundance profoundly impacts the world’s oceanic circulation.

AN EQUATION THAT IS OUT OF BALANCE

Thus, the persistence of plankton marine life in the world's oceans has reduced by over half since 1950, and the present die-off rate is more than one percent each year. At this rate, marine life is likely to be brought to its knees in the next 25 to 30 years. Actual oxygen levels in the atmosphere are decreasing at a much higher rate than carbon dioxide levels are increasing, which is problematic. That is why the loss of plants — especially marine plants — has contributed to the mentioned imbalance.

Life on Earth provides a delicate equation where the amount of carbon released into the atmosphere is neutralized by the amount of plants absorbed. In the past years, we have neglected the oceans, and more than 80% of marine life will be dead as we approach the ocean's acidification end point of pH 7.95 in just 25 years. Ocean acidification is primarily caused by the absorption of excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The waves of the ocean capture the carbon dioxide, and in response, the water becomes slowly more acidic.

The equation is out of balance and leads to climate change, and we will never be able to equal the equation again. If we destroy marine life, humanity cannot survive without the marine life support system.

The carbon balance of the planet is that 11.1 gigatons of carbon dioxide produced by burning fossil fuels and burning trees enters the atmosphere, but only 5.9 gigatons are absorbed by marine and land plants. By reducing the amount of carbon dioxide that we are producing, we can bring the equation into balance again, but this will not be enough; we need to rebuild the marine life of the ocean.

If net carbon is brought to zero by 2030, we can still have 5 to 10 more years of replenishment of ocean life. But to fight climate change and achieve net zero by 2050, people will inevitably lose the ocean's life support system. The current ocean surface average pH is about 8.1, a release of approximately 0.3 percent from the pre-industrial level, depending on the marine ecosystem.

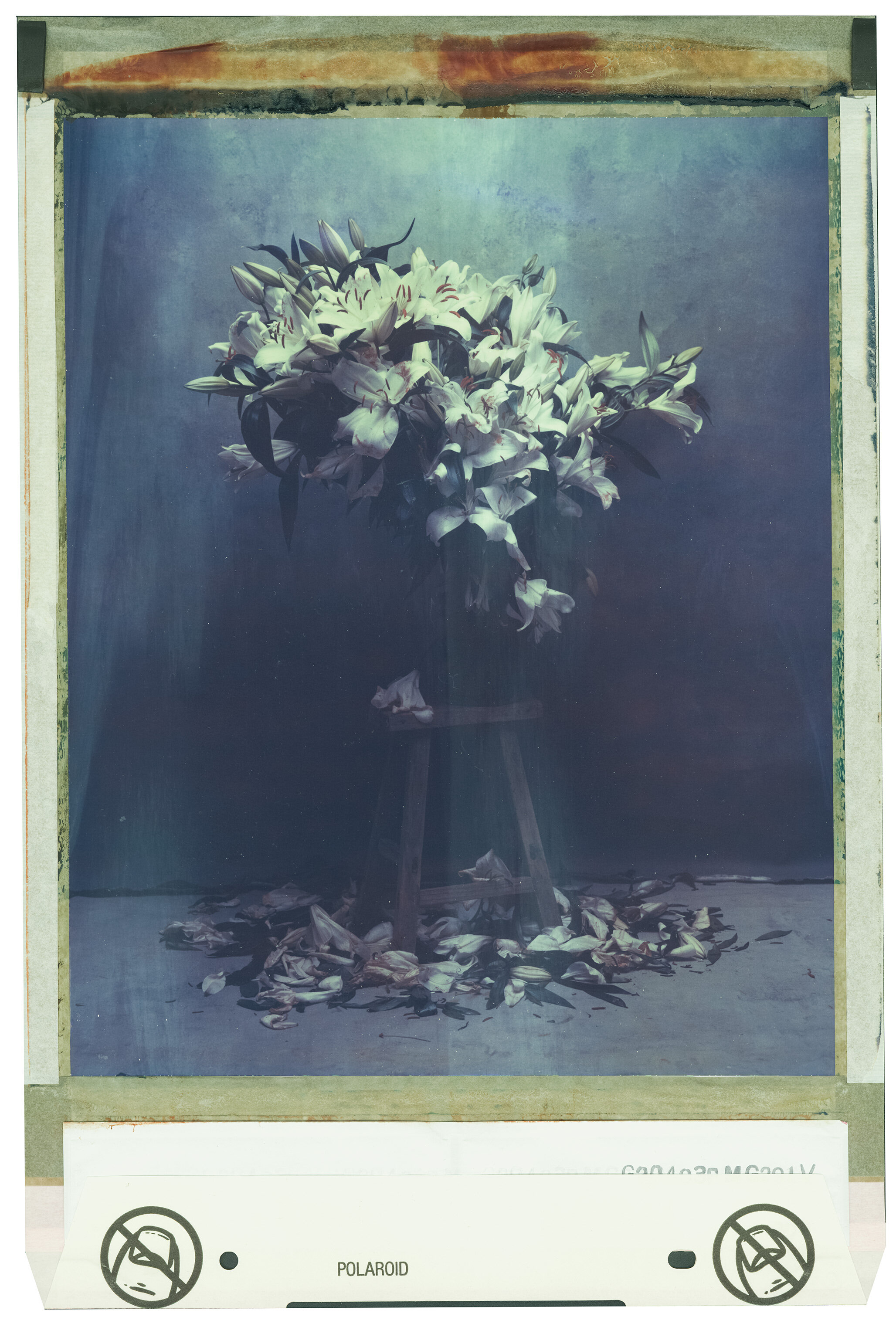

The amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere increase, and the oceans retain heat. This leads to a rise in temperature within the seas, which results in thawing the ice in the Arctic and Antarctic. These temperature changes influence phytoplankton, the large algae blooms that work as a shield by reflecting sunlight into space are shrinking, leading again to an increase in the temperature of the oceans and our planet.

Shrinking numbers of phytoplankton have an influence on the formation of clouds.

Clouds

Our climate relies on cloud formation, and phytoplankton are very important. These microscopic organisms secrete a chemical known as DMSP or dimethyl sulfoniopropionate, enabling them to live in water bodies with high salinity. DMSP releases when phytoplankton are dying or when it is released fecally, and its subsequent conversion is to a gaseous form known as DMS. This gas bubbles up from the ocean and has a smell, which means it contains phytoplankton.

When in the atmosphere, DMS initiates a chemical process that forms tiny particles called sulfate aerosols. These aerosols act as seeds for cloud formation since water vapor coalesces on them to form clouds. For every qualitative increase in sulfate aerosols, more water droplets are facilitated, and the clouds produce thicker whiteness to reflect more sunlight into space, like an umbrella that reflects heat back to the universe.

The cooling effect plays an immense role in altering the Earth's temperature. Increases in the phytoplankton population through blooms can help to increase cloud formation, which in turn cools the planet. Also, those blooms, which are on the surface level of our oceans, act like a reflector sending sunlight and heat back to the universe.

Also, the evaporation of rain cools the planet while meeting the water needs of terrestrial plants, which, in turn, helps in the conversion of carbon dioxide into oxygen.

Microplastics

Globally, the conventional perception used to be that dilution was an acceptable solution for discharging pollutants into seawater. Nevertheless, it has not been quite beneficial in addressing such an issue as microplastic pollution. Nanoplastics can refer to any plastic fragments up to five millimeters in size, and these fragments can absorb hazardous chemicals from their surroundings.

Most toxic chemicals are lipophilic, meaning they are insoluble in water and have an affinity more or less like oil. Instead, they stick to hydrophobic microplastic particles, which leads to the formation of toxic hotspots. These microplastics become carriers of all sorts of toxins, and marine life, such as fish and zooplankton, consumes the accumulated pollutants. Many microplastics can pass through the cell tissues of phytoplankton directly and cause significant toxic effects that affect phytoplankton growth, reproductive ability, and overall mortality.

Microplastics and bioaccumulated toxins originate from various sources, such as sunscreens and industrial wastewater discharge, not to mention debris that finds its way into the oceans. This is a complex pollution issue because pollution affects the marine environment in many forms, which poses a serious menace to these ecosystems.

This Series Saved My Life

When I began my project, I never thought that I would come across such gorgeous and varied species as phytoplankton. First of all, I did not have any vision. However, now it is as if I am being compared to the grandeur of the mountain top, the top where a magnificent view of the region is achieved.

I never imagined the scale at which phytoplankton contributes to the Earth's life system or how I would be part of a project exploring the core of life and climate throughout the planet. What I never got to know in school is that the ocean is, in fact, the life support system of our planet, while knowing that whales feed on plankton and trees produce oxygen. It is a privilege to have had the chance to enact this project, which has profoundly influenced my life as a living being.

I'm not an activist; I happen to care for our planet, Earth, nature, and the seas. As a result, I now have a much greater need to protect the ocean and the climate. I wish to conclude with a word from the UN conference in Lisbon in 2022:

„This means that pollution emissions, such as those resulting from plastics, chemicals, and toxic particles, are projected to rise by 2 to 4 folds within a span of 25 years unless there is a change in the rate at which this is expected to happen. At least up to 10 years from now, CO2 emissions will continue to rise. Eighty percent of the world has no effluent treatment.

The pumping of pollution and climate change harms marine phytoplankton, and this limits the ability of the ocean to neutralize acidification. The marriage of Mg calcite and aragonite will dissolve or be seriously stressed, and diatoms with pH sensitivity and silica are also threatened. Despite achieving carbon neutrality by 2030, the IPCC reveals that concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere will surpass 500 ppm and that the pH of oceans will be less than 7.95. The representatives of 1 of each of the two main varieties of marine life species have decreased their populations since 1950. With higher levels of pollution, acidification of waters, and temperature, there will be a change of regime in the seas. All the whales, seals, birds, and fish will die, along with the food that three billion people need.

Thus, it has been established that addressing climate change solely through carbon reduction measures is impossible. Combined with the die-off of one-celled organisms from the surface water in the oceans and anomalously high temperatures, it is quite feasible that we may be headed for unmanageable climate change, even if we are carbon neutral or even carbon negative. We also require the renewal of land greening and marine greening of the oceans.

If this task is not achieved together with carbon mitigation strategies, it will be catastrophic, and an organized extinction of human life over the next 15 to 30 years is guaranteed. – The final declaration of the Lisbon UN conference in 2022.“

However, a ray of hope remains from the worst nightmares found in the global seas themselves. New studies about the ecosystem carried out by the youngest advances of marine biologists show that some phytoplankton can survive in a polluted aquatic environment. Some phytoplankton proved fairly robust and capable of absorbing microplastics and other toxic substances and breaking them down. This discovery is a ray of light while combating the problem of ocean pollution.

In addition, an experimental project called "Ocean Guardians" has been developed to solve the problem of disturbed seascapes using IT tools and indigenous experience. Drones fly around the ocean without any human intervention; they are used to clean the seas, nurse marine life, and monitor their well-being. Citizens of coastal regions can save their coastal waters through sustainable living.

Enduring presence and innovative spirit – nature is opening the gates to a novel epoch that will come to be known as the epoch of responsible conduct towards the environment. The path is long, but it is possible to reverse the damages with reasonable efforts and good strategies being put in place by many individuals. The same oceans that seemed to be condemned to death by pollution are the oceans that bring a definite chance of resurrection, which, in the darkest hours, instills faith in the return of dawn.